The War of 1812 ended many of the problems that had plagued the United States since the Revolution. The nation's independence was confirmed. The long war between Britain and France was over, and with it the need for America to maintain a difficult neutrality. The war had convinced Democratic-Republicans that, for the nation's security, they must protect American industry through tariffs -- taxes on imported goods. The Republicans even chartered a new national bank to control the nation's supply of money, something they had vigorously opposed only twenty years before. The Federalist Party, meanwhile, had discredited itself through its opposition to the war. As Republicans co-opted Federalist positions, the Federalist Party withered away and became essentially extinct outside of New England.

In the elections of 1816, the first after the war's end, the Republicans took complete control of the federal government. James Monroe succeeded James Madison as President, and Republicans won 146 of 185 seats (78%) in the House of Representatives. By Monroe's second term in office -- which he won almost unanimously -- the Federalists were reduced to only 4 seats in the U.S. Senate. Monroe's administration, from 1817 to 1825, became known as the "Era of Good Feelings" because there was so little opposition to him or to his policies.

New conflicts

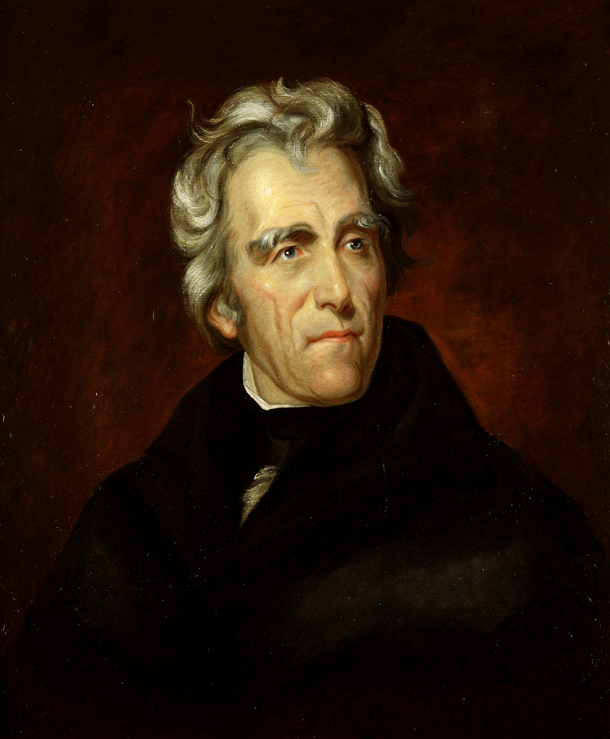

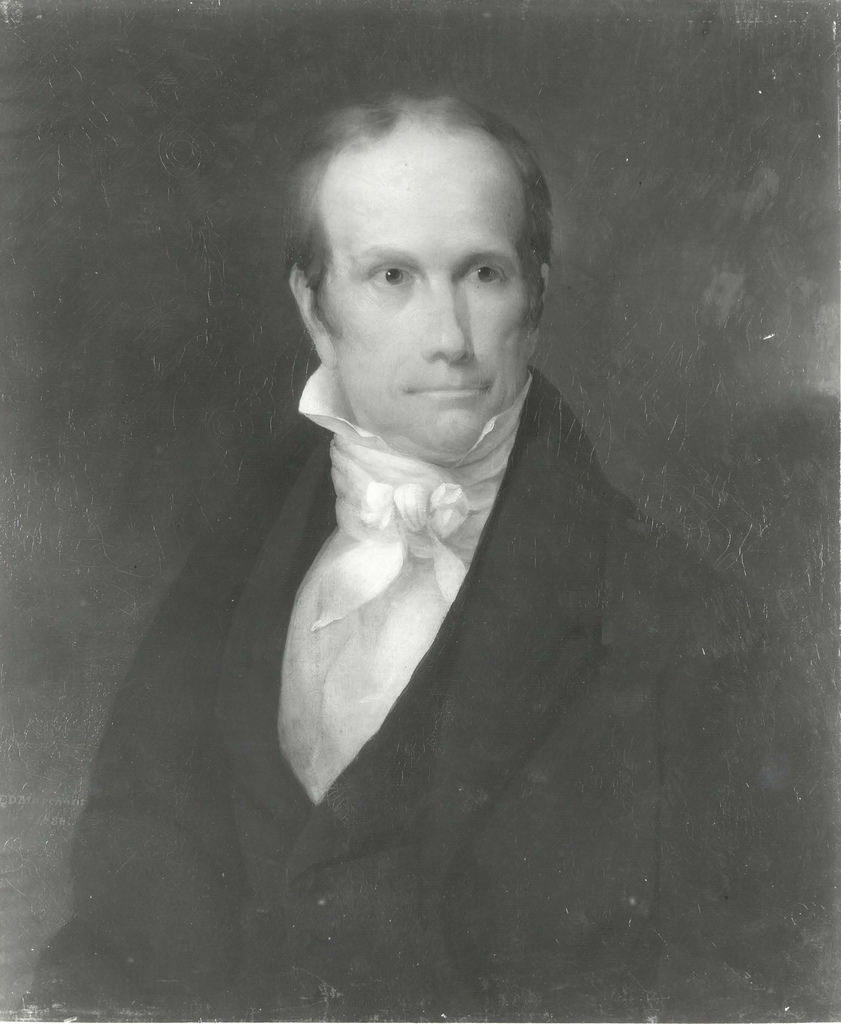

But this one-party system masked real differences in opinion. In 1824, four candidates were nominated to succeed Monroe as President, all calling themselves Democratic-Republicans: the war hero Andrew Jackson, Speaker of the House Henry Clay, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, and Secretary of the Treasury William Crawford. None of the candidates won a majority of the electoral vote, and so election was decided by the House of Representatives. Clay had great influence as Speaker of the House, and he threw his support to Adams -- some said, in exchange for Adams' promise to make Clay his Secretary of State. Jackson had won the most electoral votes and the greatest share of the popular vote, and his supporters, who had expected him to be confirmed by the House as President, called this partnership between Adams and Clay a "corrupt bargain."

During Adams' administration, his supporters, who included many former Federalists, began to call themselves "National Republicans" to show their support for a strong national government that would promote commerce, support education, and fund roads and canals. But Adams was not particularly popular. In contrast, Jackson was extremely popular, having won national fame as hero of the Battle of New Orleans in the War of 1812 and later in wars against American Indians in Florida. He was also backed by a well-orchestrated political organization. Jackson's followers formed the Democratic Party, claiming to be the true successors of Jefferson's Democratic-Republican Party. Like their predecessors, the Democrats believed in small, decentralized government.

Jackson was elected President in 1828 on a wave of popular democracy. Presidential electors had once been chosen by state legislatures, but by 1828, they were chosen by popular vote in all but two states (Delaware and South Carolina). Most states now had universal white male suffrage or had very low property requirements for voting. Jackson supporters portrayed Adams as elitist who believed that only the few, best and smartest people should rule, while Adams' supporters portrayed Jackson as a "mere military chieftain." The Democrats won by appealing directly to the common people, even using the first campaign songs. In the process, they built the first modern political party in America, with a national organization and direct campaign methods.

Jackson's inauguration reflected this new, more open democracy -- and not in an entirely positive way. While most previous presidents had been inaugurated indoors and in private, Jackson was inaugurated outdoors, on the East Portico of the Capitol. More than 20,000 people came to witness the event, even though in an era before microphones and loudspeakers, most could not hear Jackson speak. The crowd followed the new president to the White House, where the doors were opened for a public reception. Jackson eventually left through a window to escape the mob, which broke thousands of dollars' worth of china and was dispersed only by the promise of alcoholic punch on the White House lawn. Although Jackson's opponents were horrified by the display, they would soon learn to campaign to crowds as successfully as Jackson.

Tariffs and nullification

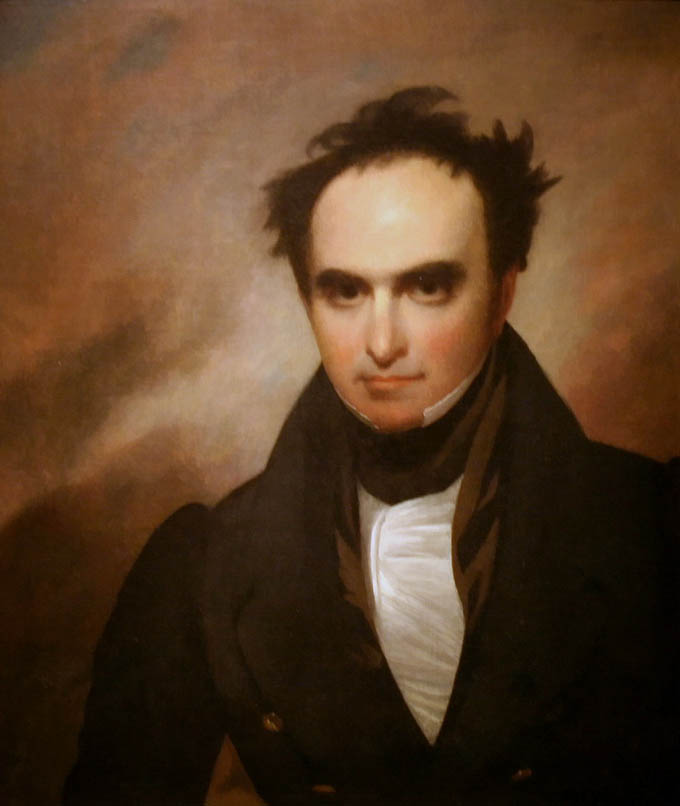

Two conflicts during Jackson's administration helped to cement the new party division. First was a conflict that came to be known as the "nullification crisis." South Carolina, like most southern states, opposed protective tariffs. Its economy was agricultural, and it imported most manufactured goods. Southerners tended to see tariffs as benefiting only the North. In 1832, South Carolina passed an "Ordinance of Nullification," declaring that it could "nullify" -- make null, or wipe out -- federal law as it saw fit. With the full support of the state's most powerful political figure, John Calhoun -- who was Jackson's vice-president -- the legislature declared that the federal tariffs of 1828 and 1832 would not be enforced within its borders. Jackson threatened to use the U. S. Army to enforce the law -- and South Carolina threatened to secede from the Union if the federal government tried to enforce the tarriff.

South Carolina had expected support of other southern states, but received none. Georgia, which might have supported nullification, was content to receive military help in removing American Indians from the state. In 1833, a compromise tariff was passed, and Congress authorized the president to use the military to enforce federal law. The crisis passed, but the idea of nullification -- that a state could ignore federal law, or even leave the union altogether, as it chose -- was far from dead.

The national bank

The second great conflict of Jackson's presidency was over the second Bank of the United States. Today, the federal government has such power and influence over the nation's economy that it may be difficult to understand why people were so strongly opposed to a national bank.

The first Bank of the United States had been chartered in 1791, under the leadership of Alexander Hamilton. It was a private corporation, only partially owned by the government, and its profits went to stockholders. But the bank had three important and unique privileges. First, the federal government deposited all tax receipts into the bank. Second, the bank made short-term loans to the government.

Third, and most important, the national bank refused to accept notes from other banks in individual states unless those banks had enough gold and silver to back up their paper. At that time, all official U.S. money was in coin, but banks issued "bank notes" -- pieces of paper with a promise to pay a stated value in gold or silver when they were redeemed or brought back to the bank. These notes could be traded for goods and services, and so they functioned as paper money. If banks issued too much paper money, though, inflation would result -- prices would rise, and the dollar would be worth less -- and if the banks did not have the assets to back up their promises, people would be left holding worthless paper, the financial system could crash. (That is essentially what happened in the financial crisis of 2008: Banks lent far more money than they had assets to pay out. ) The Bank of the United States was meant to prevent such a disaster from happening, much like today's Federal Reserve.

To Republicans, though, the bank seemed elitist. Private stockholders earned interest on government deposits. And in the South and West, money had always been in short supply (remember the protests of the Regulators). Southerners and westerners believed that the development of their regions depended on access to money and credit -- which the national bank did not give them.

The bank's charter expired in 1811, and the Republican Congress did not renew it. But the result was just what Hamilton had feared -- inflation and confusion over the value of bank notes. To provide for a sound national currency, Congress chartered a second bank of the United States in 1816, again for twenty years. And again, it was resented as elitist -- by state and local bankers who resented its privileges, and by people in new states and territories who needed access to money and credit.

When Congress voted to renew the bank's charter early, President Jackson vetoed the bill with a speech railing against monopoly and privilege. Until that time, presidents had rarely used the veto to override the wishes of Congress. But his veto was popular, and after his re-election in 1832, he issued an executive order ending the deposit of government funds into the Bank of the United States. By issuing an executive order, he was essentially refusing to enforce the act of Congress that had chartered the bank. Jackson's acts served as precedents that would concentrate power in the executive branch.

The rise of the second party system

As the Democratic Party took shape around Jackson, his opponents came together in opposition to him. The opposition coalesced into the Whig Party, which named itself after the Whigs of the Revolution and of eighteenth-century Britain who opposed the strong monarchy. Their choice of a name implied that Jackson was taking too much power and might, if left unchecked, make himself a king. Some Whigs especially feared that Jackson, as a former general, would use the military to consolidate his power. The Whigs would continue to believe that the legislature should have the most power in government, while the Democrats would continue to support a strong executive.

Whigs were strong proponents of social order. At a time when "Jacksonian democracy" and religious revivals weakened established order and the influence of traditional elites, many wealthy lawyers and businessmen and members of older churches found a home in the Whig Party. But not all Whigs were elites; the party attracted many men who wanted to improve their position in the world. Whigs also led antebellum reform movements, working to reform prisons and treatment of the mentally ill, discouraging alcohol consumption, and supporting public schools. They saw these reforms, like their efforts to promote commerce and build roads and canals, as a way of building a more orderly society.

By 1840, the Whigs had built a party organization as strong as the Democrats'. Borrowing their opponents' strategies, they nominated a war hero for president, William Henry Harrison of Ohio, who had earned fame in the War of 1812 and in conflicts with American Indians on the frontier. Like Jackson, he came from the democratic, egalitarian West. The Whigs, like the Democrats, campaigned through rallies, barbecues, debates, songs, and slogans. The Democratic incumbent, Martin Van Buren, had been Jackson's vice-president, but he was not nearly as popular as his predecessor, and the Panic of 1837 -- a serious economic recession -- made Americans ready for a change of leadership. Harrison won in a landslide.

The Whigs accomplished little with their new power, though, because a month after his inauguration, Harrison died. His vice-president, John Tyler, now became president. But Tyler was a Virginian who like most southerners supported states' rights and a low tariff, and he fought the Whig majority in Congress during his four years in office.

Whigs and Democrats in North Carolina

In North Carolina, support for the Whig Party came mainly from the less-developed parts of the state, especially the west and the northeast, where people wanted education and internal improvements that would increase economic opportunity. Against them were the wealthy planters of the east, who saw no need for reforms that would only benefit others and reduce their power in the state.

Whig power grew quickly in the state. In 1832 David L. Swain, a representative from Buncombe County, was elected governor. Swain supported the programs that Archibald Murphey had put forward fifteen years earlier, and thanks to his efforts, the state held a convention in 1835 to amend its constitution. The resulting changes gave more power to western North Carolina and made the governor elected directly by popular vote, instead of by the legislature. In 1836, the Whigs elected another governor, Edward Dudley, and they would hold onto that office until 1850. During their time in power, they funded turnpikes and railroads, chartered state banks, and established a system of public education.

By the 1850s, the Democrats had come to support the Whig plan of internal improvements -- just as Democratic-Republicans had adopted similar ideas from Federalists after the War of 1812. The issue of slavery, meanwhile, would soon come to dwarf all others on the national stage, and the resulting debates would reshape the nation's political parties again.