Disaster in the making

As early as 1925, then-Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover had warned President Coolidge that stock market speculation was getting out of hand. Yet in his final State of the Union Address, Coolidge saw no reason for alarm. "No Congress...ever assembled has met with a more pleasing prospect than that which appears at the present time," said Coolidge early in 1929. "In the domestic field there is tranquility and contentment... and the highest record of prosperity in years."

Al Smith was the Democratic nominee for President in 1928. Al Smith's campaign manager, General Motors executive John J. Raskob, agreed. In an article entitled "Everybody Ought to be Rich" Raskob declared, "Prosperity is in the nature of an endless chain and we can break it only by refusing to see what it is." President-elect Hoover disagreed. Even before his inauguration he urged the Federal Reserve to halt "crazy and dangerous" gambling on Wall Street by increasing the discount rate the Fed charged banks for speculative loans. He asked magazines and newspapers to run stories warning of the dangers of rampant speculation.

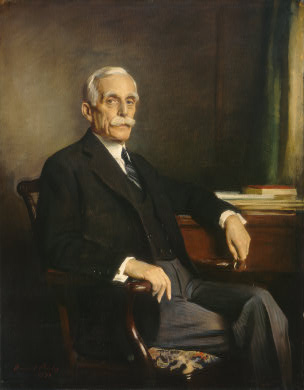

Once in the office, the new president ordered a reluctant Andrew Mellon, his holdover secretary of the treasury, to promote the purchase of bonds instead of stocks. He sent his friend Henry Robinson, a Los Angeles banker, to convey a cautionary message to the financiers of Wall Street -- and received in return a long, scoffing memorandum from Thomas W. Lamont of J.P. Morgan and Company. When the Federal Reserve Board that August did take steps to check the flow of speculative credit, New York bankers defied Washington, the National City Bank alone promising $100 million in fresh loans. An angry Hoover let the president of the New York Stock Exchange know that he was thinking of regulatory steps to curb stock manipulation and other excesses. Yet he undercut his own threat by placing ultimate responsibility for such measures on New York State's new governor, Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Presidents in 1929 were not supposed to regulate Wall Street, or even talk about the gyrating market for fear of inadvertently setting off a panic. Hoover had his own reasons for keeping quiet. His conscience was pained after a friend took his advice to buy an issue that later nosedived. "To clear myself," the president told intimates, "I just bought it back and I have never advised anybody since."

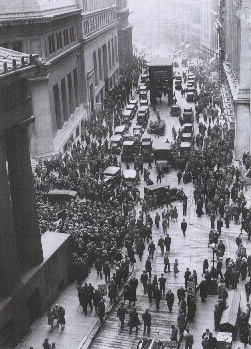

By early September, 1929 the market was topping out, some eighty two points above its January plateau. In eighteen months, General Electric had tripled in value, reaching $396 per share. Other blue chips, fueled by more than $8 billion in brokers' loans, enjoyed similar rises. The last week of October, however, brought a terrible reckoning. On October 24 alone, radio stocks lost 40% of their paper value. Montgomery Ward surrendered thirty-three points. Big bankers tried and failed to stem the dizzying decline in U.S. Steel, a bellwether stock.

A day of reckoning

On Black Tuesday, the twenty-ninth, the market collapsed. In the words of a gray haired Stock Exchange guard, "They roared like a lot of lions and tigers. They hollered and screamed, they clawed at one another collars. It was like a bunch of crazy men. Every once in a while, when Radio or Steel or Auburn would take another tumble, you'd see some poor devil collapse and fall to the floor."

In a single day, sixteen million shares were traded -- a record -- and thirty billion dollars vanished into thin air. Westinghouse lost two thirds of its September value. DuPont dropped seventy points. The "Era of Get Rich Quick" was over. Jack Dempsey, America's first millionaire athlete, lost $3 million. Cynical New York hotel clerks asked incoming guests, "You want a room for sleeping or jumping?"

Refusing to accept the "natural" economic cycle in which a market crash was followed by cuts in business investment, production and wages, Hoover summoned industrialists to the White House on November 21, part of a round robin of conferences with business, labor, and farm leaders, and secured a promise to hold the line on wages. Henry Ford even agreed to increase workers' daily pay from six to seven dollars. From the nation's utilities, Hoover won commitments of $1.8 billion in new construction and repairs for 1930. Railroad executives made a similar pledge. Organized labor agreed to withdraw its latest wage demands.

The president ordered federal departments to speed up construction projects. He contacted all forty-eight state governors to make a similar appeal for expanded public works. He went to Congress with a $160 million tax cut, coupled with a doubling of resources for public buildings and dams, highways and harbors. In December of 1929, Hoover's friend Julius Barnes of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce presided over the first meeting of the National Business Survey Conference, a task force of four hundred leading businessmen designated to enforce the voluntary agreements. Looking back at the year, the New York Times judged Commander Richard Byrd's expedition to the South Pole -- not the Wall Street crash -- the biggest news story of 1929.

Praise for the President's intervention was widespread. "No one in his place could have done more," concluded the New York Times in the spring of 1930, by which time the Little Bull Market had restored a measure of confidence on Wall Street. "Very few of his predecessors could have done as much." On February 18 Hoover announced that the preliminary shock had passed, and that employment was again on the mend. In June, a delegation of bishops and bankers called at the White House to warn of spreading joblessness. Hoover reminded them of his successful conferences with business and labor, and the explosion of government activity and public works designed to alleviate suffering. "Gentlemen," he concluded, "you have come six weeks too late."

Boom and bust

For most of our history Americans have been resigned to the "boom and bust" school of economics. When the economy got overheated and speculation ran rampant, a crash was unavoidable. Under such circumstances the best government could do was to do nothing that might make a bad thing worse. "Panics" had occurred in the 1830s under President Martin Van Buren, in the 1850s under James Buchanan, during Ulysses Grant's term in the 1870s and, most notably, under Grover Cleveland in the 1890s.

None of these presidents did much to stem the deflation in prices, contraction of investment, and loss of jobs that resulted -- for the simple reason that standard economic theory held there was little if anything they could do. Then, in 1921, a post war slump led President Warren Harding to name Hoover as chairman of a special conference to deal with unemployment. "There is no economic failure so terrible in its import," Hoover declared at the time, "as that of a country possessing a surplus of every necessity of life in which numbers...willing and anxious to work are deprived of dire necessities. It simply cannot be if our moral and economic system is to survive.

This view explains President Hoover's vigorous counterattack in the wake of Wall Street's initial tumble. Not all of his advisers were so willing to abandon Boom and Bust theories. As late as 1930, Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon held that a panic might not be such a bad thing. "It will purge the rottenness out of the system," he added. "High costs of living...will come down. People will work harder, live a moral life. Values will be adjusted, and enterprising people will pick up the wrecks from less competent people." Mellon lost out, however, and was packed off to the Court of Saint James.

Why the "Great" Depression?

Economists are still divided about what caused the Great Depression, and what turned a relatively mild downturn into a decade long nightmare. Hoover himself emphasized the dislocations brought on by World War I, the rickety structure of American banking, excessive stock speculation and Congress' refusal to act on many of his proposals. The president's critics argued that in approving the Smoot-Hawley Tariff in the spring of 1930, he unintentionally raised barriers around U.S. products, worsened the plight of debtor nations and set off a round of retaliatory measures that crippled global trade.

Neither claim went far enough. In truth Hoover's celebration of technology failed to anticipate the end of a postwar building boom, or a glut of 26,000,000 new cars and other consumer goods flooding the market. Agriculture, mired in depression for much of the 1920's, was deprived of cash it needed to take part in the consumer revolution. At the same time, the average worker's wages of $1,500 a year failed to keep pace with the spectacular gains in productivity achieved since 1920. By 1929 production was outstripping demand.

The United States had too many banks, and too many of them played the stock market with depositors' funds, or speculated in their own stocks. Only a third or so belonged to the Federal Reserve System on which Hoover placed such reliance. In addition, government had yet to devise insurance for the jobless or income maintenance for the destitute. When unemployment resulted, buying power vanished overnight. Since most people were carrying a heavy debt load even before the crash, the onset of recession in the spring of 1930 meant that they simply stopped spending.

Together government and business actually spent more in the first half of 1930 than the previous year. Yet frightened consumers cut back their expenditures by ten percent. A severe drought ravaged the agricultural heartland beginning in the summer of 1930. Foreign banks went under, draining U.S. wealth and destroying world trade. The combination of these factors caused a downward spiral, as earning fell, domestic banks collapsed, and mortgages were called in. Hoover's hold the line policy in wages lasted little more than a year. Unemployment soared from five million in 1930 to over eleven million in 1931. A sharp recession had become the Great Depression.