The attack on Pearl Harbor was the culmination of a decade of deteriorating relations between Japan and the United States over the status of China and the security of Southeast Asia. The breakdown began in 1931 when Japanese army extremists, in defiance of government policy, invaded and overran the northern-most Chinese province of Manchuria. Japan ignored American protests, and in the summer of 1937 launched a full-scale attack on the rest of China. Although alarmed by this action, neither the United States nor any other nation with interests in the Far East was willing to use military force to halt Japanese expansion.

Over the next three years, war broke out in Europe and Japan joined Nazi Germany in the Axis Alliance. The United States applied both diplomatic and economic pressures to try to resolve the Sino-Japanese conflict between Japan and China. The Japanese government viewed these measures, especially an embargo on oil, as threats to their nation's security. By the summer of 1941, both countries had taken positions from which they could not retreat without a serious loss of national prestige. Although both governments continued to negotiate their differences, Japan had already decided on war.

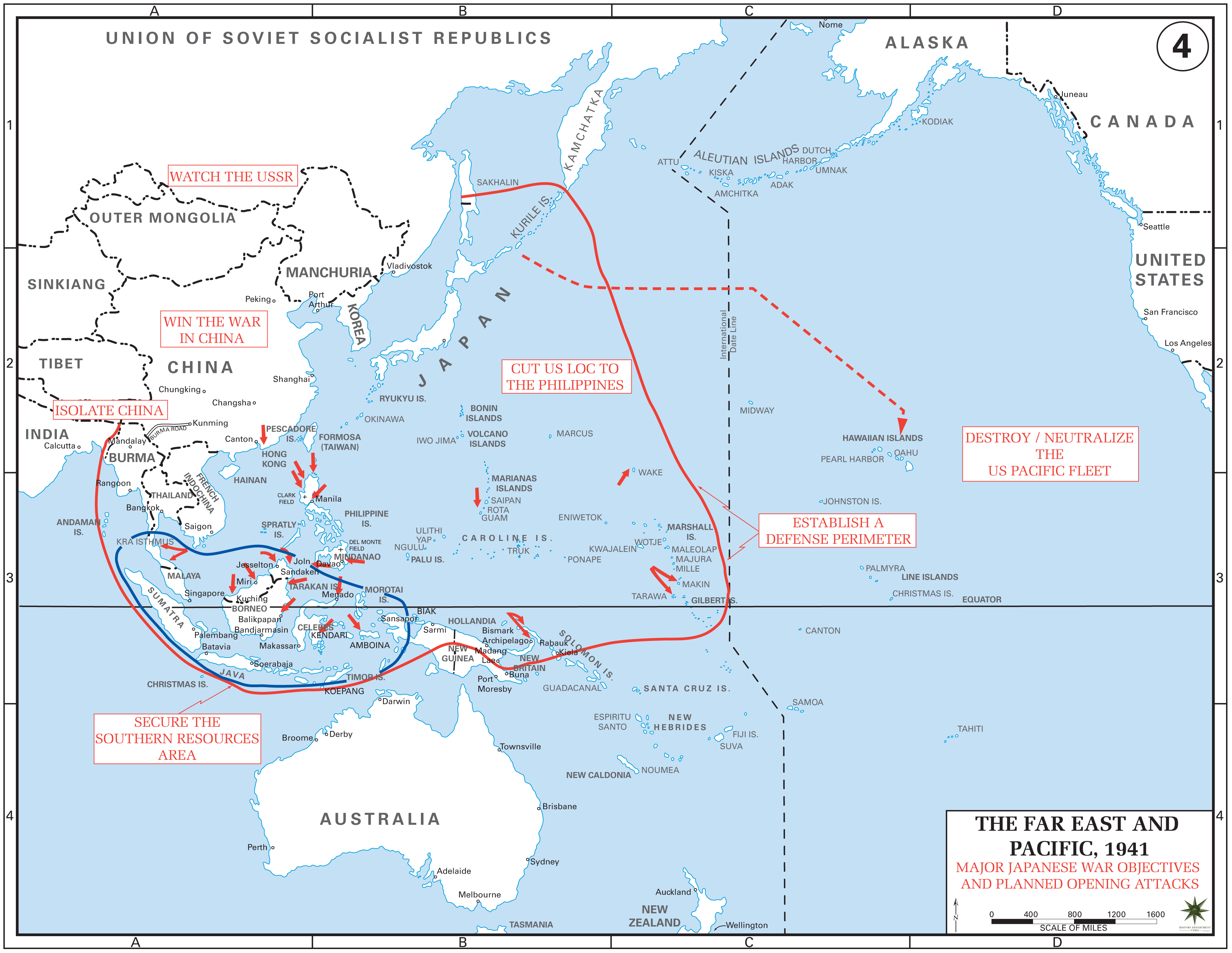

The attack on Pearl Harbor was part of a grand strategy of conquest in the Western Pacific. The objective was to immobilize the Pacific Fleet so that the United States could not interfere with these invasion plans. The principal architect of the attack was Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Commander-in-Chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet. Though personally opposed to war with America, Yamamoto knew that Japan's only hope of success in such a war was to achieve quick and decisive victory. America's superior economic and industrial might would tip the scales in her favor during a prolonged conflict.

On November 26, the Japanese attack fleet of 33 warships and auxiliary craft, including six aircraft carriers, sailed from northern Japan for the Hawaiian Islands. It followed a route that took it far to the north of the normal shipping lanes. By early morning, December 7, 1941, the ships had reached their launch position, 230 miles north of Oahu. At 6 am, the first wave of fighters, bombers, and torpedo planes took off. The night before, some 10 miles outside the entrance to Pearl Harbor, five midget submarines carrying two crewmen and two torpedoes each were launched from larger "mother" subs. Their mission: enter Pearl Harbor before the air strike, remain submerged until the attack got underway, then cause as much damage as possible.

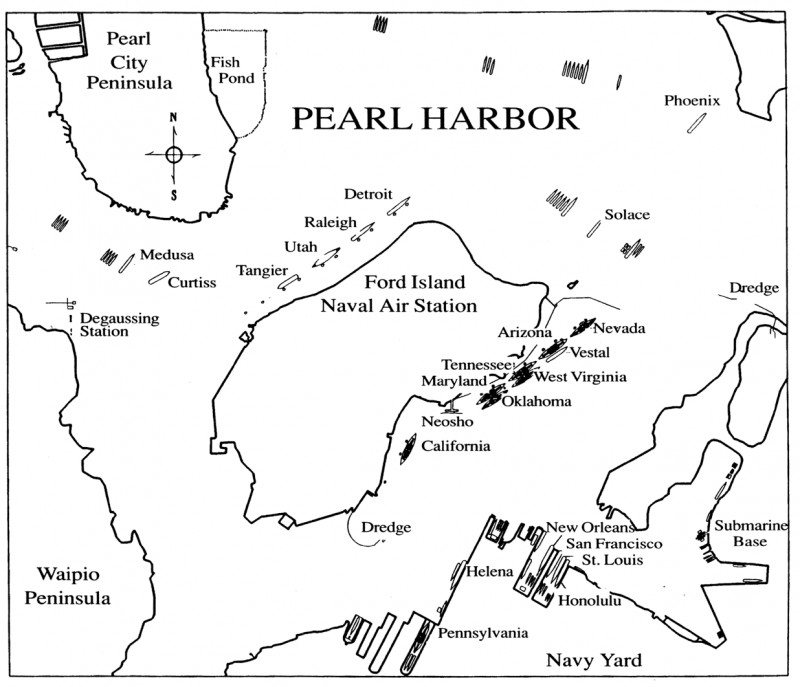

Meanwhile at Pearl Harbor, the 130 vessels of the U.S. Pacific Fleet lay calm and serene. Seven of the Fleet's nine battleships were tied up along "Battleship Row" on the southeast shore of Ford Island. Naval aircraft were lined up at Ford Island and Kaneohe Bay Naval Air Stations, and at Ewa Marine Corps Air Station. The aircraft belonging to the U.S. Army Air Corps were parked in groups as defense against possible saboteurs at Hickam, Wheeler, and Bellows airfields.

While the attack on Pearl Harbor intensified, other military installations on Oahu were hit. Hickam, Wheeler, and Bellows airfields, Ewa Marine Corps Air Station, Kaneohe Bay Naval Air Station, and Schofield Barracks suffered varying degrees of damage, with hundreds of planes destroyed on the ground and hundreds of men killed or wounded.

At 6:40 am, the crew of the destroyer USS Ward spotted the conning tower of one of the midget subs headed for the entrance to Pearl Harbor. The Ward sank the sub with depth charges and gunfire, then radioed the information to headquarters.

Before 7 am, the radar station at Opana Point picked up a signal indicating a large flight of planes approaching from the north. These were thought to be either aircraft flying in from the carrier USS Enterprise or an anticipated flight of B-17s from the mainland, so no action was taken.

The first wave of Japanese aircraft arrived over their target areas shortly before 7:55 am. Their leader, Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, sent the coded messages "To, To, To" and "Tora, Tora, Tora," telling the fleet that the attack had begun and that complete surprise had been achieved.

At approximately 8:10 am, the USS Arizona exploded, having been hit by a 1,760 pound armor-piercing bomb that slammed through her deck and ignited her forward ammunition magazine. In less than nine minutes, she sank with 1,177 of her crew, a total loss. The USS Oklahoma, hit by several torpedoes, rolled completely over, trapping over 400 men inside. The USS California and USS West Virginia sank at their moorings, while the USS Utah, converted to a training ship, capsized with over 50 of her crew. The USS Maryland, USS Pennsylvania, and USS Tennessee, all suffered significant damage. The USS Nevada attempted to run out to sea but took several hits and had to be beached to avoid sinking and blocking the harbor entrance.

After about five minutes, American anti-aircraft fire began to register hits, although many of the shells that had been improperly fused fell on Honolulu, where residents assumed them to be Japanese bombs. After a lull at about 8:40 am, the second wave of attacking planes focused on continuing the destruction inside the harbor, destroying the USS Shaw, USS Sotoyomo, a dry dock, and heavily damaging the Nevada, forcing her aground. They also attacked Hickam and Kaneohe airfields, causing heavy loss of life and reducing American ability to retaliate.

Army Air Corps pilots managed to take off in a few fighters and may have shot down 12 enemy planes. At 10 am the second wave withdrew to the north, and the attack was over. The Japanese lost a total of 29 planes and five midget submarines, one of which was captured when it ran aground off Bellows Field. The commander of this midget submarine, Ensign Sakamaki, became the first U.S. captured prisoner of the Pacific war.

The attack was a great, but not total, success. Although the U.S. Pacific Fleet was shattered, its aircraft carriers (not in port at the time of the attack) were still afloat and Pearl Harbor was surprisingly intact. The shipyards, fuel storage areas, and submarine base suffered no more than slight damage. More importantly, the American people, previously divided over the issue of U.S. involvement in World War II, rallied together with a total commitment to victory over Japan and her Axis partners.