Colonial legacies

Slavery has been part of North Carolina's history since its colonization by Europeans in the late 1600s and early 1700s. Many of the first enslaved people in North Carolina were brought to the colony from the West Indies or other surrounding colonies, but a significant number were brought from Africa. Records were not kept of the tribes and homelands of enslaved African people, so it is impossible to know the exact ethnic and cultural make-up of North Carolina's population of enslaved people.

Because of its geography, North Carolina's initial trade of enslaved people was limited. The string of islands that make up its Outer Banks made it dangerous for ships carrying enslaved people to land on most of North Carolina's coast, and most enslavers chose to land in ports to the north or south of the colony. The one major exception is Wilmington. It became a port for& ships carrying enslaved people due to its accessibility as it sits on the Cape Fear River. By the 1800s, black people in Wilmington outnumbered white people 2 to 1. The town benefited due to the abilities of enslaved peoples' trades. Professional skills of enslaved people, like carpentry, masonry, and construction, as well as skill in sailing and boating, made Wilmington grow and succeed as a city.

The colony also lacked the extensive plantation system of the Lower South colonies. When Carolina split into the North and South colonies in 1729, North Carolina had about 6,000 enslaved people in it, a fraction of the population of enslaved people in South Carolina. As the plantation system expanded across the Lower South, many enslaved people in North Carolina were "sold south" to work on these large plantations. Enslaved people and families deeply feared this fate because it usually meant permanent separation from friends and family.

Because extensive records were not kept, and many existing records have been lost, there is little known of enslaved people in the North Carolina colony beyond basic information. By 1767, there were about 40,000 enslaved people in the colony. About 90 percent of these enslaved people were field workers who performed agricultural jobs. The remaining 10 percent were mainly domestic workers, and a small number worked as artisans in skilled trades, such as butchering, carpentry, and tanning.

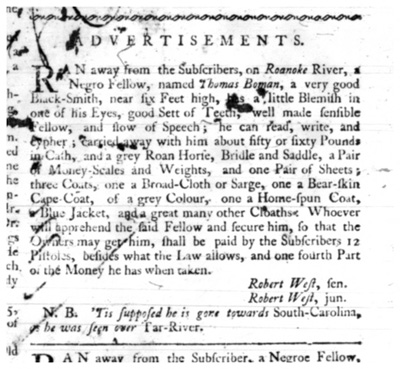

Records do exist detailing the colonial laws that white enslavers and politicians enacted to control enslaved people. The first set of these laws, the North Carolina Slave Code of 1715, required enslaved people to carry a ticket from their enslaver whenever they left the plantation. The ticket stated where they were traveling and the reason for their travel. The 1715 code also prevented enslaved people from gathering in groups for any reason, including religious worship, and required white people to help capture escaped freedom-seeking enslaved people.

A second set of even stricter laws was put into place in 1741. These laws prevented enslaved people from raising their own livestock and from carrying guns without their enslaver's permission, even for hunting. The law also limited manumission, or freeing of enslaved people. It stated that an enslaver could only free an enslaved person for "meritorious services," and even then the decision had to be approved by the county court. Perhaps the most serious of all the laws was regarding "runaway slaves," or escaped freedom-seeking enslaved people. It stated that if freedom-seeking enslaved people refused to surrender immediately, they could be killed and there would be no legal consequences.

After the Revolution

The ban on importing enslaved people to North Carolina was lifted in 1790, and the state’s population of enslaved people quickly increased. By 1800, there were around 140,000 black people living in North Carolina. A small number of these were free black people, who mostly farmed or worked in skilled trades. The majority were enslaved, working in agriculture on small- to medium-sized farms. As in the colonial period, few enslaved people in North Carolina lived on huge plantations. Fifty-three percent of enslavers in the state owned five or fewer enslaved people, and 2.6 percent of enslaved people lived on farms with over 50 other enslaved people during the antebellum period. By 1850, 91 enslavers in North Carolina owned over 100 enslaved people.

Because they lived on farms with smaller groups of enslaved people, the social dynamic of enslaved people in North Carolina was somewhat different from their counterparts in other states, who often worked on plantations with hundreds of other enslaved people. In North Carolina, the hierarchy of enslaved domestic workers and enslaved field workers was not as developed as in the plantation system in other southern states. There were fewer numbers of enslaved people to specialize in each job. Thus, on small farms, enslaved people may have been required to work both in the fields and at a variety of other jobs at different times of the year. Another result of working in smaller groups was that North Carolina enslaved people generally had more interaction with enslaved people on other farms. Enslaved people often looked to other farms to find a spouse, and traveled to different farms to court or visit during their limited free time.

The slave codes passed in the colonial period continued to be enforced during the antebellum years. White people hoped these laws would prevent threats of uprisings of enslaved people, which terrified enslavers across the state. In 1829, David Walker, a free black author born in Wilmington, gave white enslavers and sympathizers in North Carolina another reason to fear their enslaved people turning against them. Walker was an avid abolitionist who moved from his home state of North Carolina to Boston, where he helped escaped enslaved people establish new lives. He wrote and published a pamphlet, Walker’s Appeal, calling for immediate freedom for all enslaved people and urging enslaved people to rebel as a group. Copies of the pamphlet were smuggled into Wilmington via ships from the Northern U.S., and then spread throughout the state.

White enslavers and sympathizers reacted to Walker’s Appeal by passing increasingly restrictive laws surrounding enslaved people. Nervous leaders in North Carolina passed legislation in 1830 making it illegal to distribute the pamphlet in hopes of quelling Walker's radical ideas about abolishing slavery. Another North Carolina law passed in 1830 made it a crime to teach an enslaved person to read or write. Laws were even extended to restrict the rights of free black people. An 1835 law prevented free black people from voting, attending school, or preaching in public.

These restrictive laws were also passed in response to the increase in uprisings of enslaved people in nearby states, such as the Nat Turner Rebellion just across the border in Virginia. In 1831, Nat Turner led a group of 75 escaped enslaved people in an uprising, during which the group killed about 60 white enslavers and sympathizers before being captured by the state militia. White enslavers and sympathizers in North Carolina were appalled at the thought of a similar rebellion happening in their state, and hoped severe laws surrounding enslaved people would prevent such uprisings.