After the Civil War, thousands of recently freed Black and white farmers forced off their land by the bad economy lacked the money to purchase the farmland, seeds, livestock, and equipment they needed to begin farming again. Former planters were so deeply in debt that they could not hire workers. They needed workers who would not have to be paid until they harvested a crop — usually one of the two labor-intensive cash crops that still promised to make money: cotton or tobacco. Many of these landowners divided their lands into smaller plots and turned to a tenant system. During the Gilded Age, many Black and white Americans lacked the money to buy farmland and farm supplies. They became tenant farmers and sharecroppers.

Tenant farmers usually paid the landowner rent for farmland and a house. They owned the crops they planted and made their own decisions about them. After harvesting the crop, the tenant sold it and received income from it. From that income, he paid the landowner the amount of rent owed.

Sharecroppers seldom owned anything. Instead, they borrowed practically everything — not only the land and a house but also supplies, draft-animal, tools, equipment, and seeds. The sharecropper contributed his, and his family’s, labor. Sharecroppers had no control over which crops were planted or how they were sold. After harvesting the crop, the landowner sold it and applied its income toward settling the sharecropper’s account. Most tenant farmers and sharecroppers bought everything they needed on credit from local merchants, hoping to make enough money at harvest time to pay their debts.

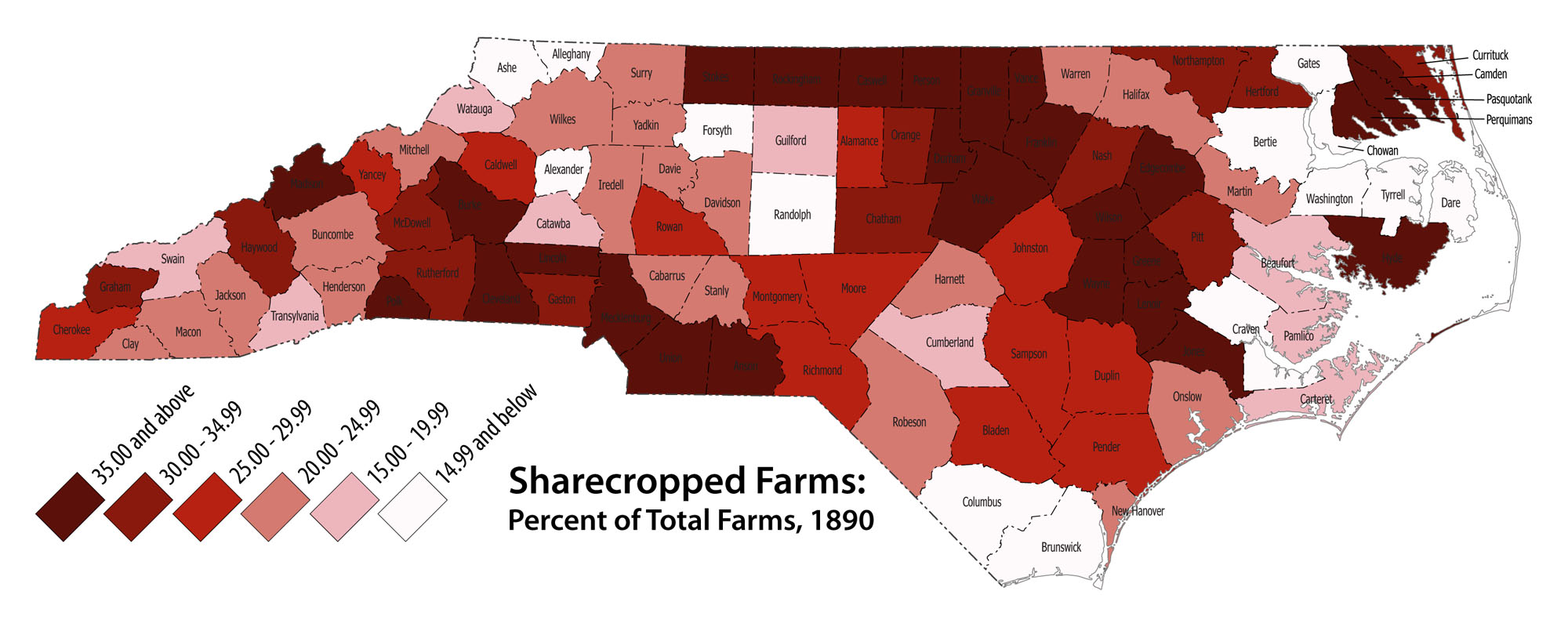

Over the years, low crop yields and unstable crop prices forced more farmers into tenancy. The crop-lien system kept many in an endless cycle of debt and poverty. Between 1880 and 1900, the number of tenants increased from 53,000 to 93,000. By 1890, one in three white farmers and three of four black farmers were either tenants or sharecroppers.