Nearly 200,000 men lost their lives from enemy fire during the four years of the war. However, more than 400,000 soldiers were killed by an enemy that took no side -- disease.

From our modern perspective, medicine during the Civil War seems primitive. Doctors received limited medical education. Most surgeons lacked familiarity with gunshot wounds. The newly-developed minie ball produced grisly wounds that were difficult to treat. The Northern and Southern medical departments were ill-prepared for removing wounded men from the battlefield and transporting them to hospitals. Systems to provide hospital care for the sick and wounded had not been developed. Blood typing, X-rays, antibiotics, and modern medical tests and procedures were nonexistent.

Open latrines, decomposing food, and unclean water were the rule in the camps. Diarrheal diseases affected nearly every soldier and killed hundreds of thousands of men. Although surgeons used ether and chloroform routinely as anesthetics, surgery was performed with unwashed hands and unclean instruments, resulting in infected wounds. The most effective drugs were the pain-killers opium and morphine, while many of the other available drugs were useless or harmful. Despite these limitations, Civil War doctors achieved some remarkable successes in treating the wounded and comforting the sick.

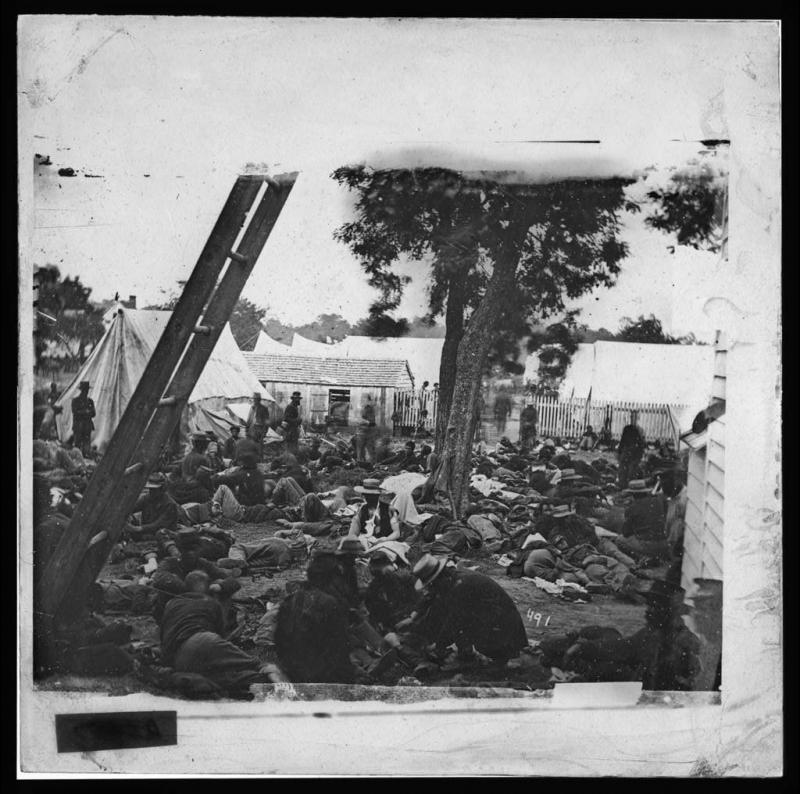

Popular but generally incorrect images of Civil War medicine involve surgery-amputations without anesthesia, piles of arms and legs, the surgeon as a butcher. By modern standards, wartime surgery was limited. Despite the lack of both surgical experience and sanitary conditions, the survival rate among those who underwent the knife was better than in previous wars. Amputation was not the only surgical recourse available. Surgeons also extracted bullets, operated on fractured skulls, reconstructed damaged facial structures, and removed sections of broken bones.

As bullets hit their victims, shattered bone and shredded flesh became the calling cards of the minie ball. Most of the surgeons who had come from civilian practices had little or no experience in dealing with such wounds. They quickly became aware of the surgical options: remove the limb, remove the fractured portions of bone, or clean the wound and apply a dressing. Union surgeons documented nearly 250,000 wounds from bullets, shrapnel, and other missiles. Fewer than 1,000 cases of wounds from sabers and bayonets were reported.

Walt Whitman Describes a Battlefield Hospital

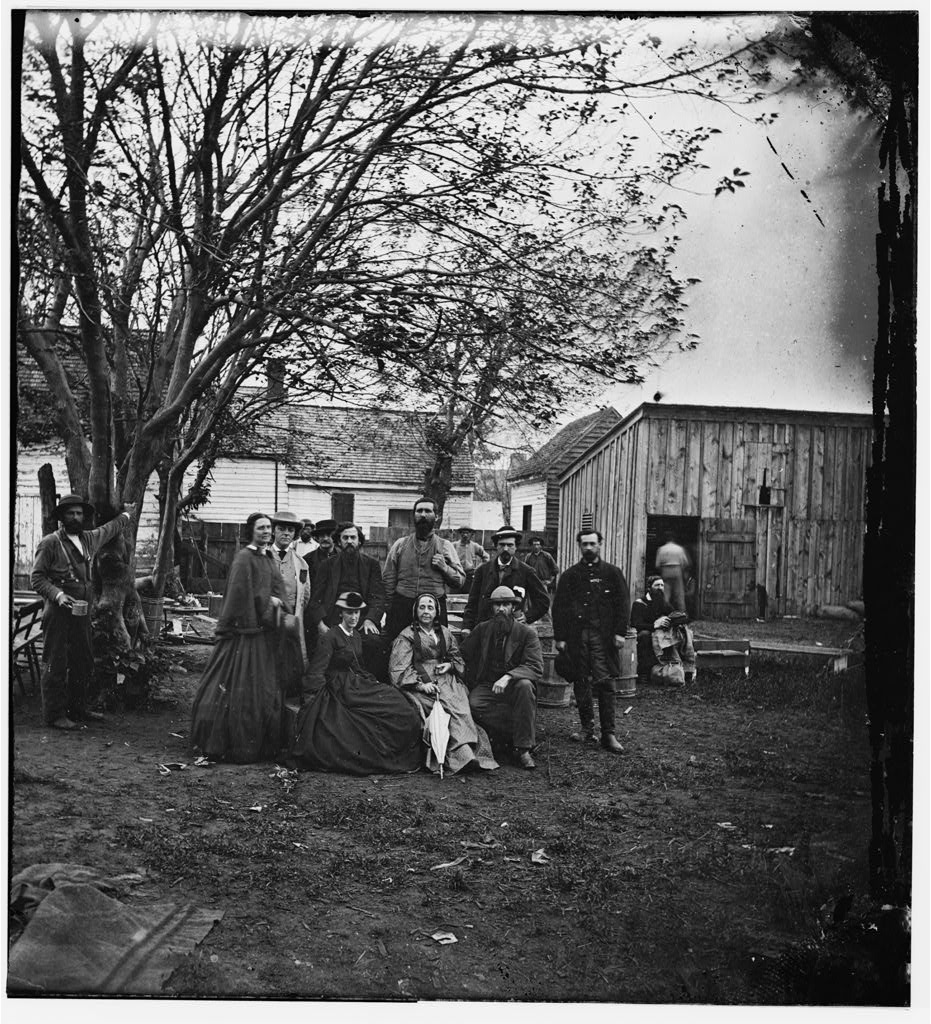

Walt Whitman, the renowned American poet, visited D.C. hospitals during the Civil War and published several works inspired by his experiences in these hospitals and the war in general. These Civil War-inspired works include the famed "Oh Captain! My Captain" as well as the poetry collection Drum-Taps and published prose Specimen Days. Below is an excerpt from Specimen Days.

DOWN AT THE FRONT

Falmount, Va., opposite Fredericksburgh, December 21, 1862.

Begin my visits among the camp hospitals in the army of the Potomac. Spend a good part of the day in a large brick mansion on the banks of the Rappahannock, used as a hospital since the battle -- seems to have receiv'd only the worst cases. Out doors, at the foot of a tree, within ten yards of the front of the house, I notice a heap of amputated feet, legs, arms, hands, &c., a full load for a one-horse cart. Several dead bodies lie near, each cover'd with its brown woolen blanket. In the door-yard, towards the river, are fresh graves, mostly of officers, their names on pieces of barrel-staves or broken boards, stuck in the dirt. (Most of these bodies were subsequently taken up and transported north to their friends.) The large mansion is quite crowded upstairs and down, everything impromptu, no system, all bad enough, but I have no doubt the best that can be done; all the wounds pretty bad, some frightful, the men in their old clothes, unclean and bloody. Some of the wounded are rebel soldiers and officers, prisoners. One, a Mississippian, a captain, hit badly in leg, I talk'd with some time; he ask'd me for papers, which I gave him. (I saw him three months afterward in Washington, with his leg amputated, doing well.) I went through the rooms, downstairs and up. Some of the men were dying. I had nothing to give at that visit, but wrote a few letters to folks home, mothers, &c. Also talk'd to three or four, who seem'd most susceptible to it, and needing it.

Source Citations:

"To Bind Up the Nation's Wounds: Medicine During the Civil War." National Museum of Health and Medicine (NMHM). Accessed June 05, 2019. https://www.medicalmuseum.mil/index.cfm?p=visit.exhibits.past.nationswou....

Whitman, Walt. Specimen Days & Collect. Philadelphia: Rees Welsh & Co, 1822-83. https://archive.org/details/specimendayscoll00whit/page/n5