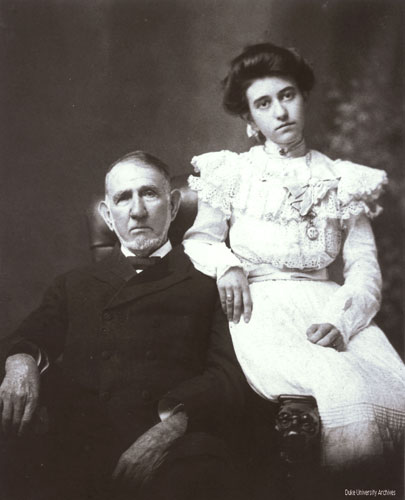

Washington Duke had left home around the time of his twenty-first birthday to take up tenant farming. The son of Taylor Duke, a farmer and respected neighborhood leader who served as captain of the local militia and also as district deputy sheriff, Washington was the eighth of ten children. His basic education was gleaned from behind the handles of a plow in the rugged, rural setting into which he was born in the year 1820. As a young man, family and church exercised the most influence over him and throughout his life both his family and the Methodist faith would remain important. Years later his son, James B. Duke, remarked: "My old daddy always said that if he amounted to anything in life it was due to the Methodist circuit riders who frequently visited his home and whose preaching and counsel brought out the best that was in him.

On August 9, 1842, Washington Duke married Mary Caroline Clinton. Two children, Sidney Taylor and Brodie Leonidas, were born to the couple, but in November 1847, Mary Caroline passed away. Left with two small sons to raise, Duke continued as a farmer, raising such crops as corn, wheat, oats, and sweet potatoes. He had acquired his first land in 1847 from the estate of his father-in-law and had purchased additional property until he now had accumulated over three hundred acres.

Washington turned his attention to providing a substantial home to shelter his family and completed the residence -- now called Duke Homestead -- in time for his marriage to Artelia Roney of Alamance County on December 9, 1852. The family soon increased from four to seven members with the births of Mary, Benjamin, and James Buchanan Duke. Duke worked hard at farming, performing most of his duties without the benefits of enslaved laborers. Though records indicate that he enslaved one person, an enslaved woman who served as a housekeeper, it is known that he participated in the custom of hiring enslaved laborers from larger farms and plantations.

Life was running smoothly for Washington Duke when in 1858 misfortune struck again. His fourteen year old son, Sidney, became ill with typhoid fever; while trying to nurse the boy back to health, Artelia Duke also contracted the disease. Both she and Sidney died. Once again Duke faced the responsibility of raising his family alone. He managed with the aid of Artelia's sisters, Elizabeth and Anne, who volunteered to help run the household. Washington Duke apparently joined the Confederate Army in late 1863 or early 1864. Though he was a Unionist who opposed secession and remained unsympathetic to the Confederacy, Duke was unable to remain aloof for long from personal participation in the war. Because of a shortage of troops the Confederate government enacted conscription laws which forced men up to the age of forty-five to join the service. Thus Washington was compelled to join the army and had to make arrangements for his family and farm before he entered the service. He sent his children to the Roney home in Alamance County, except for Brodie who accompanied him into the service.

Duke decided to sell all his farm belongings and had converted all his means into tobacco by the end of 1863. It is not clear whether he sold or rented the homestead; however, he was to receive payment in leaf tobacco which was to be stored on the property.

During his brief military career, Duke was captured by Union forces and imprisoned in Richmond, Virginia. At the end of the war the Federals released and shipped him to New Bern, North Carolina. Lacking money and transportation, the veteran walked back to his homestead -- a distance of 135 miles.

Where it all began

Washington Duke's trek back to Orange County after the Civil War marked the beginning of his rise to prominence in the tobacco business. He gathered his family and returned to his virtually barren homeplace; having been unable to make the proper payments in tobacco during his absence, the tenants had been forced to abandon the farm to its rightful owners. Once again in full control of the property, Duke and his children began their smoking tobacco operation in a small log structure -- now known as the first factory. Though a good part of Duke's stored leaf had apparently been confiscated by soldiers while he was away, the family members were able to fashion by crude hand processes the remaining portion into smoking tobacco, which they could trade readily for needed supplies and sometimes cash.

Washington took the manufactured leaf on a peddling trip into eastern North Carolina, using a broken-down wagon and two blind mules to transport him. The trip was a success; merchants in small towns and villages were the best customers. Money realized from the sale of the tobacco was used to purchase family necessities such as lard and bacon -- and a surprise bucket of sugar for the children.

The growing business

Following his profitable sales trip, Washington Duke began the manufacture of smoking tobacco on a part time basis. Though farming tobacco, wheat, corn, oats, and other subsistence crops took up much of the family's time, the Dukes were able to manufacture 15,000 pounds of their product, "Bro Bono Publico," during the year 1866. This increase in production necessitated the utilization of other outbuildings on the farm, including an old stable--known as the second factory. Soon, in order to lessen the heavy workload and keep production up, Duke began buying additional tobacco from neighboring farmers.

Though it was difficult to make a large profit on manufactured tobacco due to the high federal revenue tax placed on it during this period, the Duke's country enterprise continued to grow steadily in the late 1860s as the market for Duke's tobacco expanded and subsequent peddling journeys were launched from the homestead. Prices for "Pro Bono Publico" increased but fluctuated over the next few years.

Building an empire

In 1868 Brodie Duke tried to persuade his father to move the manufacturing operation to Durham. Though Washington Duke decided to continue at a rural location, he provided funds for Brodie to establish his own factory in Durham, where he began production in 1870. Around that time also, Washington began to concentrate more heavily on the manufacture of tobacco; he constructed a two-story frame building -- the third factory, and hired additional workers to handle the increased production. Until that time, there had been no building on the property built specifically for the manufacture of smoking tobacco. The third factory was designed to receive and store un-manufactured tobacco and to house the manufacturing operation. The structure featured wide doors to facilitate loading and unloading of tobacco. Rafters inside the building held tier poles probably used for hanging sticks of tobacco prior to manufacture; small doors in the attic were opened or closed to regulate the moisture content of the hanging leaves. Square holes cut into the ceiling of the first floor apparently were openings for chutes. The manufactory probably contained no sophisticated machinery; no records have been found detailing the interior contents, though it must have contained such items as flails, sieves, work tables, weighing scales, and an assortment of baskets and barrels.

Still, the homestead tobacco business retained its simple, family-oriented manufacturing processes. The process of manufacture at the third factory was simple and slow--as it had been at the first and second factories in use previously. Workers flailed the cured tobacco, beating the dry leaves into a very fine state by forcing it through a sieve. Laborers then granulated the crushed leaf while other skilled workers weighed and packed the sieved tobacco. Demonstrations of processes used in early tobacco manufacturing are presented in this factory. By 1873, the Dukes were producing around 125,000 pounds of smoking tobacco annually.

As the enterprise steadily expanded, and the number of customers outside of North Carolina increased, Washington Duke began to consider the advantages of moving his business into town. Conditions in Durham in the early 1870s were very favorable for the manufacture of tobacco; the location of the North Carolina railroad station was convenient for shipping, and a warehouse for the sale of leaf tobacco had been opened in 1871. Durham was rapidly becoming a major tobacco center. In April 1874, Duke purchased two acres near the railroad where he built a new factory.

W. Duke, Sons and Company

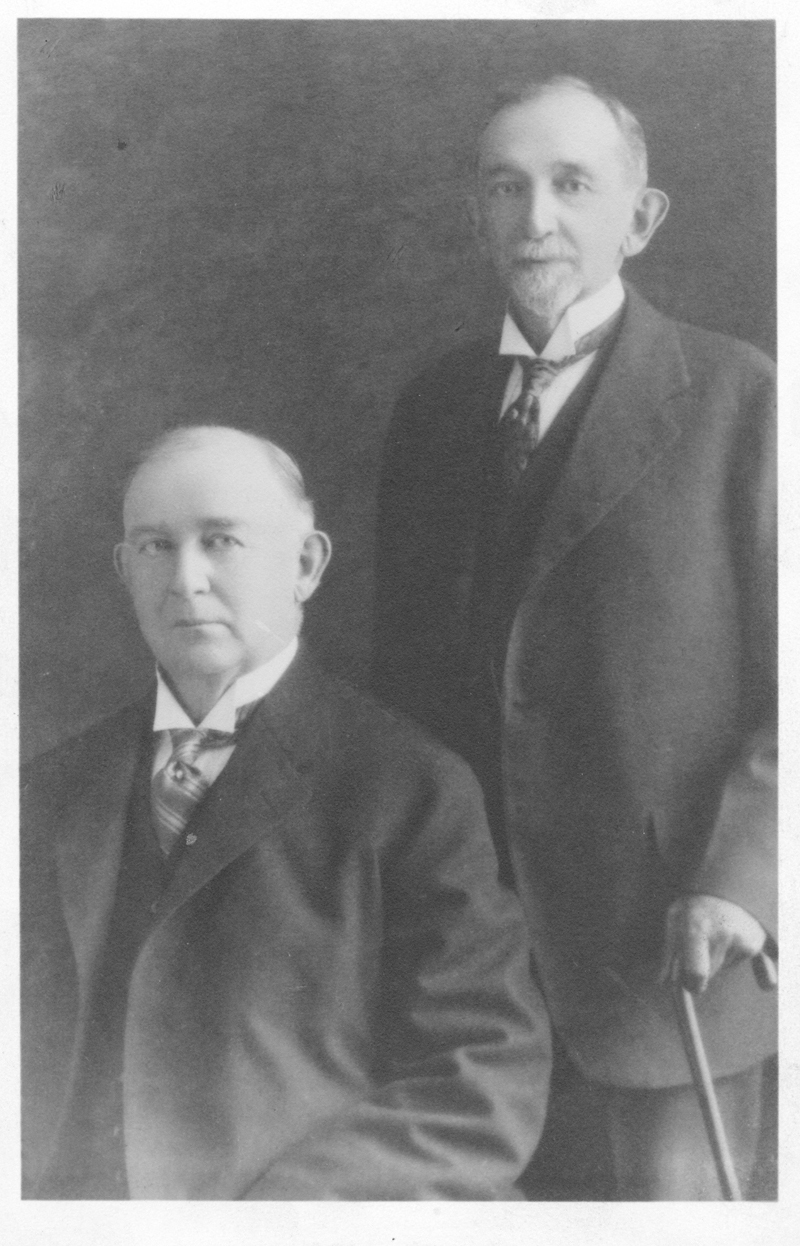

The shift into Durham in 1874 and the construction of the new factory there marked the beginning of a large scale tobacco company that climbed gradually to the top of the industry. At first, many of the basic hand methods used at the homestead were employed at the new factory. Washington Duke's sons took a more active role in the facility establishment. Brodie, who had gained experience and become moderately successful as a manufacturer during his four years in town, moved his business into one wing of the new town factory. Benjamin and Buck Duke were given equal partnerships and assumed much of the responsibility for company operation. Washington traveled throughout the country, concentrating his efforts on promotion of the company's products.

By now Washington Duke had established himself as one of the wealthiest men in Orange County and was fast emerging as a leading citizen of Durham. Affiliated with the Republican party, Duke participated as a candidate in several local and state elections.

Aside from his interest in politics, a much greater concern of Duke's was the stiff competition from other tobacco operations in the town. The old established leader was W. T. Blackwell and Company, with its "Bull Durham" smoking tobacco, which became for a time the largest firm of its kind in the world. The Dukes invited a new partner, George W. Watts of Baltimore, to join the firm in 1878 and renamed the business W. Duke, Sons and Company. The move was significant because Mr. Watts' investment broadened the company capital, enabling it to be more competitive with the older, more established firms.

Cigarettes in Durham

Although W. Duke, Sons and Company enjoyed a healthy trade in smoking tobacco, the keen rivalry with W. T. Blackwell and Company finally prompted the Dukes to begin the manufacture of cigarettes in 1881. The practice of using cigarettes had spread from the European countries to the United States around 1860. The manufacture of cigarettes extended southward to Virginia and North Carolina in the 1870s and 1880s.

Early hand methods used in cigarette production were slow and tedious; an expert could roll only about four per minute. W. Duke Sons and Company and other firms began to hire immigrants from eastern Europe who were skilled in cigarette making. As cigarettes grew in popularity, tobacco companies began the search for a mechanical method of manufacturing them rapidly. Around 1877, the Allen and Ginter Company of Richmond, Virginia, offered $75,000 to any person who could invent a practical cigarette-making machine. Such a machine was developed in 1880 by eighteen year old James Bonsack; Allen and Ginter installed the machine in their factory, but discarded it as a failure after several trials.

In 1884, however, the Duke company decided to take a chance on the imperfect Bonsack machine, leasing and installing two of the devices in the Durham factory. When working properly, the machine could perform the work of forty-eight hand rollers. When the Dukes encountered mechanical problems with the machine, The Bonsack Machine Company of Virginia sent a mechanic, William T. O'Brien, to Durham to refine the apparatus. O'Brien and James B. Duke were finally able to make the equipment work more smoothly, cutting the cost of cigarette manufacturing in half.

Believing that the new Bonsack machine eventually would eliminate hand processing of cigarettes, James B. Duke, in the spring of 1884, went to New York to establish a branch of the company there. This relieved the overburdened Durham factory and enabled the firm to gain a foothold in the national center of commerce and world trade.

W. Duke, Sons and Company was becoming the leading cigarette producer in the country. Increased advertising efforts enabled the firm to outsell its competitors. One journalist later noted that James B. Duke "was always an aggressive advertiser, devising new and startling methods which dismayed his competitors and was always willing to spend in advertising a proportion of his profits which seemed appalling to more conservative manufacturers.

Largest in the industry

By the mid-1880s Buck Duke felt that a merger of all large-scale tobacco manufacturers would be a practical way of reducing selling and advertising costs as well as improving overall organization. The four most important competitors of the Duke firm at that time were the Allen and Ginter Company of Richmond, the F. S. Kinney Company and the Goodwin Company both of New York, and William S. Kimball and Company of Rochester; these and the Duke company manufactured 90 percent of the nation's cigarettes in the 1880s. After discussing the merger, and following a period of excessive spending on advertising, the large rival firms agreed that the Dukes' plan of merger was the most sensible proposal. In 1890, the five principal companies united to form the American Tobacco Company. This combination quickly became known as the "tobacco trust" because of its almost complete monopoly of the tobacco trade.

James B. Duke in 1890 controlled the largest tobacco industry in the world; the combined firms continued to grow in the next two decades. However, by the turn of the century, anti-trust sentiment was increasing rapidly in the United States. The prevailing feeling of the public that monopolies were harmful concentrations of power resulted in the dissolution of the American Tobacco Company by a ruling of the United States Supreme Court in 1911. Four major tobacco corporations were among those companies which emerged from the separation of the trust: a new American Tobacco Company, Liggett and Myers, P. Lorillard, and R. J. Reynolds.

Following the court action, Buck Duke carried on his tobacco business abroad and invested money in the development of hydroelectric power. Later, Duke was to follow in the footsteps of his father and brother in distributing his fortune for the benefit of religious, educational, and medical institutions. Washington and Benjamin had established a pattern of giving money to support the Methodist school, Trinity College, in Durham; James B. continued the tradition when, in 1924, the Duke Endowment was created for the benefit of his native region. In addition to the establishment of Duke University, formerly Trinity College, the multi-million dollar indenture provided funds for educational institutions, orphanages, hospitals, and the Methodist church in the Carolinas. As a result of the family's generous gifts, millions of people throughout the region have enjoyed a better quality of life.

Source Citation:

"The Move into Durham." Duke Homestead Education and History Corporation. Accessed July 11, 2019. https://dukehomestead.org/the-move-into-durham.php.

"A New Product." Duke Homestead Education and History Corporation. Accessed July 11, 2019. https://dukehomestead.org/a-new-product.php.

"The Second and Third Factories." Duke Homestead Education and History Corporation. Accessed July 11, 2019. https://dukehomestead.org/the-second-and-third-factories.php.

"Washington Duke." Duke Homestead Education and History Corporation. Accessed July 11, 2019. https://dukehomestead.org/washington-duke.php.