The following passage and images are excerpted from Herbert Ladd Towle's "The Woman At the Wheel" 1915 article. He discussed women using cars shortly after their popularization. This article helps illustrate changing trends in automobile ownership.

What changes a dozen years have wrought in motoring! Men no longer buy cars for the fun of discovering why they won't go, but wholly in the prosaic expectation that they will. Little do the beginners of to-day know of the stern joys of conquest which once made every mile a triumph! To-day a man must drive his car to death to have anything more serious than arrest happen to him. And now we see women driving motor-cars for all the world as if they belonged at the wheel!

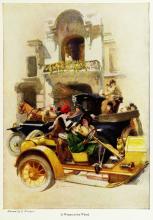

Young girls, most of them, hardly out of their teens -- they meet you everywhere, garbed in duster and gauntlets, manipulating gears and brakes with the assurance of veterans. Not always in little ladylike cars, either. If you visited last summer a resort blessed with good roads, whether East or West, you saw "sixesSix-cylinder cars. More cylinders means more power. Most cars today have four cylinders; big trucks have up to eight." of patrician fame and railroad speed, with Big Sister sitting coolly at the wheel, pausing at the post-office on their way for a country spin. And you wondered if the callow youth seated beside the competent pilot would ever have the gumption to handle a real car himself!

An amazing change, even from the view-point of only three years ago! Have the women suddenly gained courage, or have motor-cars altogether lost their formidable mien?

Something of both, no doubt, but especially something of the latter. Cars are being perfected, not merely in delicacy of control, but in the total elimination of certain demands for strength and skill. Engine-startersIn order for a car to operate, the engine has to be moving before the fuel begins burning. Once the engine is running it will power itself, but it has to be started by some other force.Until about 1920, that force was provided by the driver himself. To start an early car, the driver used a hand crank — a metal bar inserted into the front of the engine, which he used to turn the engine by hand. Hand-cranking was dangerous if done incorrectly — if the engine backfired (started to run backwards), the crank could spin out of control, and the person holding it could easily break a thumb or a wrist.By the 1920s, most cars had self-starters that used electricity from a battery to power a small motor that cranked the engine. The invention of the starter motor probably did more than any other single thing to popularize cars and driving. -- now next to universal, save on the lightest cars -- are the most notable instance. You no longer whirl a crank or dexterously "snap her over"; you merely press a foot-plunger and an electric (or sometimes pneumatic) motor spins the engine merrily till the explosions start....

A control feature that requires no strength but lots of "knowing how" is the spark advanceAn internal combustion engines requires a spark, but the spark has to be produced at the right moment. The advance spark system controlled the timing of the spark, which made starting cars more reliable and therefore easier to operate.. Many persons who handle the wheel well, but have only a vague idea of what is under the hood, never acquire that difficult art. A "spark knockSpark knock is a rattling noise that is produced when a car is working hard, such as climbing a hill. It is created when fuel burns erratically inside the internal combustion engine. This noise indicates that there is a problem with the engine of a car, such as a faulty valve." means nothing to them; they are deaf alike to the piteous pleadings of their cylinders and to the rumblings that tell of late ignition and a heated engine. For these chronic amateurs the automatic spark advance, to be found on a number of cars this year, is an unalloyed boon; and even to the seasoned driver it is a benefit, as meaning one less control to think about.

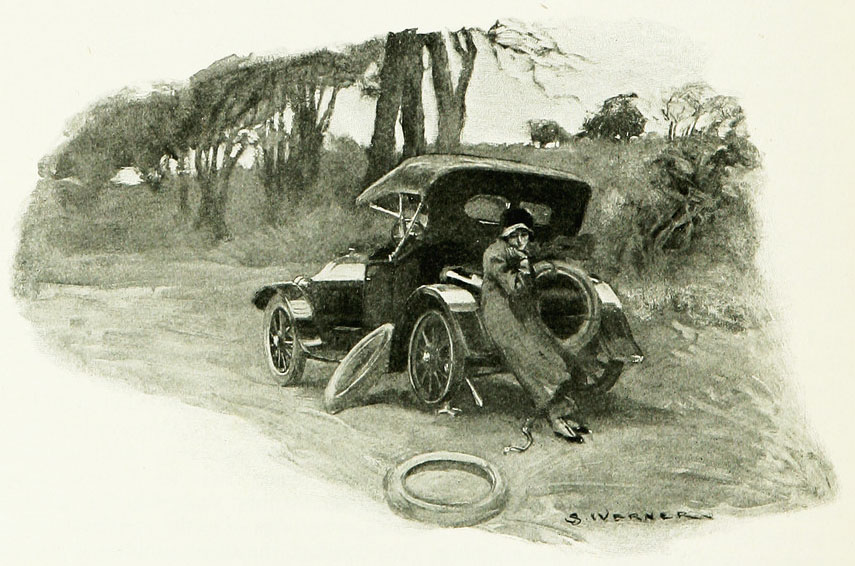

The tire problem, it must be admitted, remains in an unsatisfactory state. Power-pumps there are, but simply getting the tire on and off is no light task. With practice a woman can manage a small tire, say up to 32x32½ inches. Some can handle larger ones; but, as a rule, if even a medium-sized tire goes flat a woman must have masculine help, and if the gallant rescuer isn't at hand she must wait till he appears.

However, it is quite practicable to avoid all tire trouble by the use of suitable protectors. These, if properly made, can stay on as long as desired without injuring the tires or seriously reducing speed. They prevent punctures and cuts, and in wet weather they prevent skidding without need of special non-skid attachments. They are scarcely suited to fast going, and they must be judiciously selected, as not all types are beneficial; but for women, at least, the tire insurance they give is much more useful than speed.

Engine starters -- electric gear-shift -- automatic spark advance -- power air-pump or tire protectors -- an engine running more smoothly and tractably than ever before -- cars better built and garages more numerous; is it a wonder that so many women are driving?...

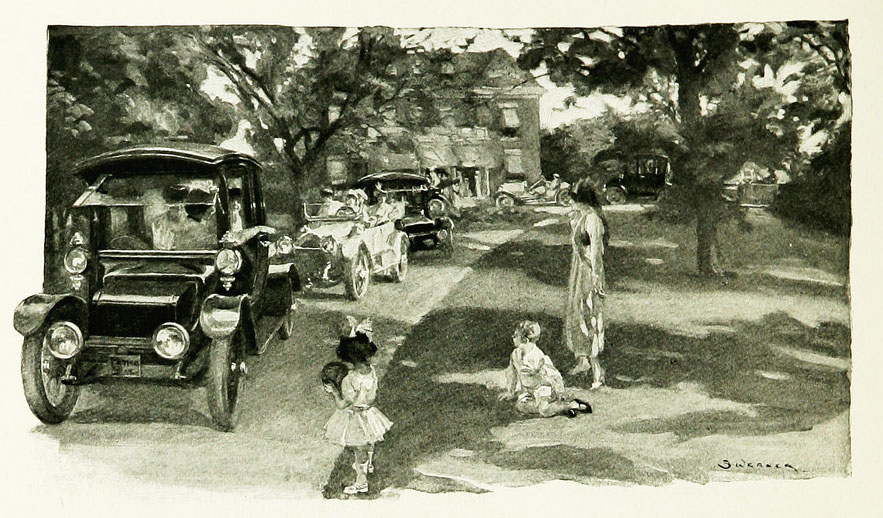

In Lenox, Mass., for example, a census of thirty-four car-owning families shows sixteen women drivers, of whom seven drive medium to high-power cars. In Stockbridge, near by, six car-owning families number -- mothers and daughters -- eleven feminine drivers, six of whom are above the small-car class!

What then? Are we who have safely outgrown the mania of haste to see it run a yet more scintillant course in our better halves? In truth, the idea of a speeding career for mother and the girls does not appeal to us. Motor speeding is essentially a man's sport, like polo, yachting, and ice-boating. All are trials of strength and nerve as well as skill. The only reason that women drive cars at all is that they may do so without courting the joys and risks of speed; and if they sometimes drive fast, it is only because the demand for strength and nerve is less than in purely masculine sports.

In reality there is less feminine speeding than might be supposed. The average woman has small taste for mechanics; she pushes this lever and pulls that with only a vague knowledge of how the final result is produced; and she is well aware that if anything goes wrong she will have to wait for masculine succor. It is really the exceptional woman, not the average one, who ventures much beyond the safe-and-sane limit of twenty-five miles an hour.

So we may look to see the majority of women content with small cars. Even the speed fever is not incurable; one good scare will go far to heal it, and, in any case, it is bound to run its course. Excitement will in time be eliminated as a motif for women's driving, save in the case of a few young girls. There remain two other motifs: the pleasure of country driving (apart from unusual speed) and plain utility work, as in shopping and visiting. Are these also transitory?

What of touring? Rural innkeepers are complaining even now of the falling off in cross-country patronage; there is little doubt that, despite the greatly increased number of cars, there is less actual touring than there was. Again it is the spur of novelty that is gone; but here it is only the novelty of speed. Few among us can devote so much time to pleasure as to exhaust the touring routes within our reach. And, with all the novelty of driving gone, there will yet be a delight in visiting new fields, in climbing new heights to survey the vistas beyond, in finding new beauty spots by lake and river and ocean, in communing afresh with the venerable woods, and in brightening old memories of perfect days be revisiting their scenes. These things uplift the spirit.

Most tours are family affairs, and I fancy that the average woman will gladly yield the responsibility to stronger hands. However self-reliant when alone, she "likes to be taken care of" when she may. And touring, even with all the mechanical aids I have named, is real work; the heavier the car and the rougher and hillier the road, the more strenuous it is. A White Mountain or even Pennsylvania tour keeps one very busy indeed, and a hundred and fifty miles of it in a day will tire any one. Hence, I fancy that, while tours will always be enjoyed, the woman's part in them will have to do with the hampersHamper in this context means a large basket with a lid, such as you’d use to pack a picnic. and personal belongings rather than with the actual management of the car.

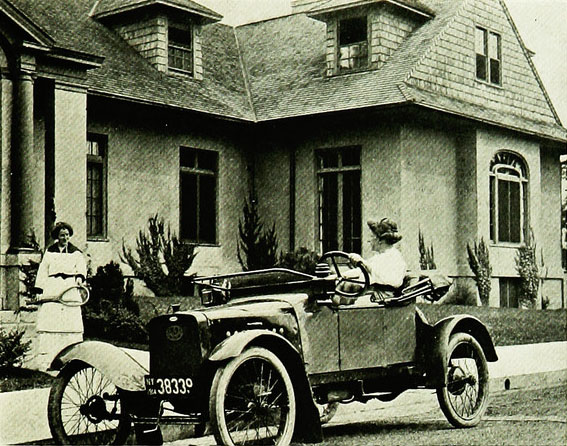

Let us turn to every-day matters -- to the life of the average woman in suburb or country. Here we find a big and vital need which, if satisfied, will make hundreds of thousands of women motorists.

The suburban man, going to business in the city, has unlimited transportation for his needs. To him his country home is a "sweet inne from care and wearisome turmoyle." But his wife and daughters don't go to the city. They must visit the butcher, the post-office, and their neighbors on foot, adding the labor of walking to that of keeping house; and for lack of time and strength they stay at home when they can. The green, open spaces about them are to their scanty powers more like prison bars than a charter of liberty!

The very limitations which deter most women from motoring for sport cry out for aid in their common duties. Unless the average woman can get about in the country both easily and freely, she will continue to prefer the near neighborhood of railroad and trolley, as she does to-day. And as she elects, you and I will follow....

The fact that the present trend is setting so strongly toward small cars is significant of the time to come when women will feel much more generally at home in them than is to-day the case; and for the present we may well be content with this, without crying too insistently for an ideal woman's car not yet in sight. We know, at any rate, that a million and three quarters pleasure cars are in use in this country, and it is a safe guess that two hundred thousand women are managing very will with the cars they have. That is surely a good beginning, and a pleasant augury of the time when the automobile's liberating mission will be fulfilled. For of one thing we are already sure -- be it ideal or only near-ideal, the woman's motor-car will have a vital place in the social economy of the future. It will supply the one link till lately missing in the chain making for a saner distribution of population and a more wholesome environment for our children. And as such we welcome it with thankful hearts.