Forces for Change: North Carolina 1820-1870

By Elizabeth A. Fenn, Peter H. Wood, Harry L. Watson, Thomas H. Clayton, Sydney Nathans, Thomas C. Parramore, and Jean B. Anderson; Maps by Mark Anderson Moore. Edited by Joe A. Mobley. From The Way We Lived in North Carolina, 2003. Published by the North Carolina Office of Research and History in association with the University of North Carolina Press. Republished in NCpedia by permission.

See also: The Way We Lived in North Carolina: Introduction; Part I: Natives and Newcomers, North Carolina before 1770; Part II: An Independent People, North Carolina, 1770-1820; Part III: Close to the Land, North Carolina, 1820-1870; Part IV: The Quest for Progress, North Carolina 1870-1920; Part V: Express Lanes and Country Roads, North Carolina 1920-2001

Amid the rising expectations and buoyant optimism of the Jacksonian era, emigration was the most critical problem facing the state. Every year thousands of energetic and capable Carolinians left their friends and farms to seek better opportunities in the West.

Legislators, planters, educators, and reformers all sought to reverse the trend by expanding opportunity within the state, though by and large the measures they proposed served only those Tar Heels who were free and white. The long-awaited North Carolina Convention in 1835 resulted in the ratification of a series of amendments aimed at liberalizing the state constitution. Henceforth, seats in the House of Commons would be apportioned solely on the basis of county population, and every white male taxpayer would be eligible to vote in statewide elections for both the lower house and the governorship. For the first time, however, free blacks were explicitly excluded from the electorate.

Ironically, North Carolinians within the government and without overwhelmingly approved of the forced emigration of a certain segment of the population on t he grounds that it could not, or would not, fully assimilate. Thus the proud remnant of the Cherokee Nation was "removed" from the southwest corner of the state by federal troops in 1838. Although the tribe had been guaranteed "inviolable" rights to its homeland in treaty after treaty with the United States, the Indians' legitimate claims were superseded by what President Andrew Jackson considered to be the demands of "civilization." Approximately one-fifth of the 18,000 Cherokees driven from their towns and farms in Georgia, North Carolina, Alabama, and Tennessee died in military detention camps while awaiting departure or along the "Trail of Tears" on their way to Oklahoma. A number of North Carolina Cherokees, however, escaped removal to the West. They and their descendants subsequently occupied the 63,000 acres of the Qualla Reservation in Swain, Jackson, and Haywood Counties

he grounds that it could not, or would not, fully assimilate. Thus the proud remnant of the Cherokee Nation was "removed" from the southwest corner of the state by federal troops in 1838. Although the tribe had been guaranteed "inviolable" rights to its homeland in treaty after treaty with the United States, the Indians' legitimate claims were superseded by what President Andrew Jackson considered to be the demands of "civilization." Approximately one-fifth of the 18,000 Cherokees driven from their towns and farms in Georgia, North Carolina, Alabama, and Tennessee died in military detention camps while awaiting departure or along the "Trail of Tears" on their way to Oklahoma. A number of North Carolina Cherokees, however, escaped removal to the West. They and their descendants subsequently occupied the 63,000 acres of the Qualla Reservation in Swain, Jackson, and Haywood Counties

Transportation and Communication

During the antebellum period, the federal government began building a new series of lighthouses on the North Carolina coast in response to the nation's growing maritime commerce. The first and prototype of the new lighthouses was the Cape Lookout Lighthouse, built in 1859. The Civil War interrupted lighthouse construction, but following the war, three more lighthouses were built in relatively quick succession at Cape Hatteras (1870), Bodie Island (1872), and Currituck Beach (1875). Each of the four had its own distinctive paint markings to distinguish it for mariners. To assist shipwreck victims, the U.S. Life-Saving Service (later called the Coast Guard) began building its stations along the North Carolina coast in the 1870s.

Many believed the solution to North Carolina's transportation problem lay in an exciting new invention: the steam locomotive. The state government stimulated railway construction by purchasing substantial portions of stock in various private railroad companies chartered by the legislature, thereby underwriting much of the cost and assuming a large share of the risk. By 1840 the first two lines were complete. The Wilmington and Weldon Railroad, which stretched 161 miles from Wilmington to the Roanoke River, was at the time the longest railway in the world. The Raleigh and Gaston line linked the capital city with the Roanoke as well, and with the existing rail connections from the river to Virginia's attractive markets.

Rail construction continued unabated until the outbreak of the Civil War, by which time approximately 900 miles of track had been laid in the state. Most important was the North Carolina Railroad, completed from Goldsboro via Raleigh to Charlotte in 1856

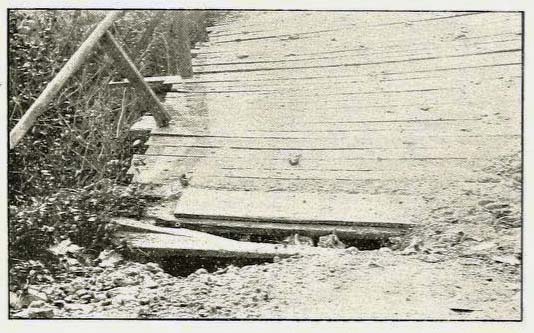

During the 1850s farmers and merchants agitated for the construction of a system of all-weather roads that would reduce the difficulty of transporting their goods to market or the nearest rail connection. The legislature chartered numerous private companies to construct "plank roads" with the modest financial backing of the state. Because most of the stock in these ventures was purchased by individual farmers living along the proposed route, plank roads came to be known as "farmers' railroads."

Although such roads were built in almost every part of the state, Fayetteville served as a focal point for their development. Six plank roads converged at this thriving market center, the longest being the Fayetteville and Western, which ran 129 miles northwest through Salem to the Moravian town of Bethania, in Forsyth County.

Although such roads were built in almost every part of the state, Fayetteville served as a focal point for their development. Six plank roads converged at this thriving market center, the longest being the Fayetteville and Western, which ran 129 miles northwest through Salem to the Moravian town of Bethania, in Forsyth County.

Industry

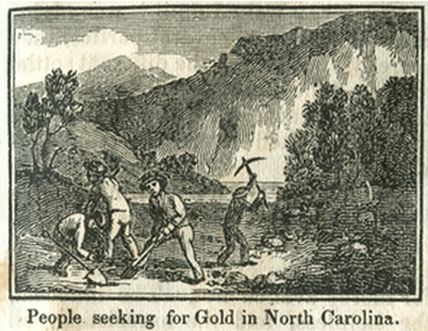

Although nineteenth-century Tar Heels mined limited quantities of iron and coal, it was gold that captivated the state's fancy. Begun on a part-time basis by Cabarrus and Mecklenburg County farmers, the gold-mining industry in North Carolina employed some 30,000 laborers and ranked second only to agriculture in economic importance at its height.

Gold was first discovered in the state in 1799 on John Reed's farm southeast of Concord, in Cabarrus County. And North Carolina's gold belt counties -- Davidson, Guilford, McDowell and Randolph -- produced the nation's gold supply from about 1800 to 1848, when the California Gold Rush began.

During the late 1820s the budding industry boomed. Rich underground veins of gold were discovered in Mecklenburg County, and the corporations that controlled them brought in experienced European miners who employed the latest and most sophisticated mining techniques. John Reed, preferring to maintain a close-knit family operation, resisted the expensive transition to vein mining and the importation of outside workers, values, technology, and capital it entailed. But within a decade the younger members of the family had sunk several shafts of up to ninety feet at Reed Mine. After John Reed's death, the property changed hands several times until purchased in 1853 by the New York-based Reed Gold and Cooper Mining Company. The firm installed the most advanced processing equipment and sank fifteen separate shafts that were connected by a series of tunnels over 500 feet in length. Despite its impressive effort, the company went bankrupt, and, though the mine continued to lure a succession of new investors, it was never successfully operated again. It is now a state historic site. The decline of the Reed mine mirrored the fate of the industry as a whole in North Carolina

The Schenck-Warlick spinning mill, in Lincoln County, the first textile factory opened in the state, was established in 1815. Shortly thereafter, Joel Battle drew on the expertise of Scotsman Henry Donaldson to set up a similar mill on the Tar River near Rocky Mount. Although the original stone structure was destroyed during the Civil War, Rocky Mount Mill operated well into the twentieth century on the same site. By the mid-1850s Edwin Holt was producing his famous "Alamance Plaids" on steam-powered looms at his mill on Great Alamance Creek, yet North Carolina's textile industry as a whole had progressed only slightly beyond the system of domestic manufactureing that it replaced. Though no other southern state could match the thirty-nine cotton textile factories operating in North Carolina, the value of the factories' combined output placed that industry no better than fifth.

The Schenck-Warlick spinning mill, in Lincoln County, the first textile factory opened in the state, was established in 1815. Shortly thereafter, Joel Battle drew on the expertise of Scotsman Henry Donaldson to set up a similar mill on the Tar River near Rocky Mount. Although the original stone structure was destroyed during the Civil War, Rocky Mount Mill operated well into the twentieth century on the same site. By the mid-1850s Edwin Holt was producing his famous "Alamance Plaids" on steam-powered looms at his mill on Great Alamance Creek, yet North Carolina's textile industry as a whole had progressed only slightly beyond the system of domestic manufactureing that it replaced. Though no other southern state could match the thirty-nine cotton textile factories operating in North Carolina, the value of the factories' combined output placed that industry no better than fifth.

Education and Reform

By 1860 "progressive" Tar Heels could boast of sixteen colleges, with a combined enrollment of over 1,500, enhancing the knowledge and virtue of the citizenry in every section of the state.

The worthy social objectives behind the creation of such institutions did not necessarily ensure their success. Davidson College, in Mecklenburg County, for example, was founded in 1837 on the basis of a noble, yet abortive, experiment. Seeking a means by which "the cost of a Collegiate education . . . might be brought within the reach of many in our land, who could not otherwise obtain it," the churchmen of Concord Presbytery organized Davidson as a "Manual Labor School." In exchange for a reduction in boarding fees, every student was required to perform three hours per day of "manual labor, either agricultural or mechanical."

The "Manual Labor System" was not the only aspect of campus life influenced by the provocative vision of social improvement. Formal literary and debating societies provided a focus for educational as well as social activity at Davidson and other colleges throughout the state. At Davidson intellectual debates and oratory were sutured in the college's elegant Eumenian Hall (1849), one of two debating halls.

War and Reconstruction

The Civil War ravaged North Carolina—both its families and its farms. Forty thousand men, more than from any other southern state, were lost in their prime. Thousands more were scarred and damaged, left with only their courage and their pride. Millions of dollars in local, state, and Confederate revenue were spent for naught as well. Investments, savings, loans, and currency were all rendered worthless with no hope of reparation. Countless banks, mills, stores, and schools were closed forever. Blighted crops, empty barnyards, fallen fences, and broken dreams all had to be dealt with in the midst of defeat.

While 125,000 Tar Heels marched off to battle in service of the Confederate States of America, almost eight times that number remained at home. Faced with scarcities, exorbitant prices, and depreciating currency, farm wives and plantation mistresses, old men and small children, free blacks and domestic servants strove to make ends meet. Houses were stripped of draperies and carpets to provide clothing and shelter for North Carolina's troops. Parched corn was substituted for coffee, and spinning wheels once more competed with power looms. Yet opportunistic merchants and unscrupulous blockade runners continued to sell their goods at the highest prices the market would bear. Bacon jumped from $.33 to $7.50 per pound, wheat went from $3 to $50 a bushel, and coffee was selling at $100 per pound.

While 125,000 Tar Heels marched off to battle in service of the Confederate States of America, almost eight times that number remained at home. Faced with scarcities, exorbitant prices, and depreciating currency, farm wives and plantation mistresses, old men and small children, free blacks and domestic servants strove to make ends meet. Houses were stripped of draperies and carpets to provide clothing and shelter for North Carolina's troops. Parched corn was substituted for coffee, and spinning wheels once more competed with power looms. Yet opportunistic merchants and unscrupulous blockade runners continued to sell their goods at the highest prices the market would bear. Bacon jumped from $.33 to $7.50 per pound, wheat went from $3 to $50 a bushel, and coffee was selling at $100 per pound.

Although the Civil War resulted in hardship for white North Carolinians, it brought the opportunity for a new life—one free of the bonds of slavery—for the state's African American population. As they heard news of the arrival of the Federal army in eastern North Carolina, thousands of them seized the opportunity to flee to freedom and security within the Union lines. The numbers of these so-called "contrabands" became such a logistical problem that camps were established to house the new "freedmen" at various locations in the occupied eastern portion of the state.

The wartime experience gained in the freedmen camps led in March 1865 to the establishment of a federally funded Freedmen's Bureau, charged with easing the transition from former slave to free citizen. The bureau operated throughout the South, with regional offices in every state. The headquarters for North Carolina were located in the impressive Greek Revival main building of what is now Peace College. Despite the bureau's efforts to assist freedmen in finding employment, negotiating fair contracts, and settling legal disputes, black Carolinians remained at a distinct political, economic, and social disadvantage. The state's conservative leadership marshaled the entrenched racism and staunch solidarity of the white population in order to thwart black achievement and to maintain control.

Although the federal government took measures to combat the Klan and protect the rights of African Americans in the South, its support and enthusiasm for Reconstruction eventually waned. By the time Reconstruction came to an end in all the southern states in 1877, white Democrats (formerly called Conservatives) had been in control of state government in North Carolina for a number of years. They persisted in their efforts to undo as much as possible the reforms of Congressional Reconstruction. With the withdrawal of federal protection, African Americans in North Carolina and the rest of the South faced an uncertain future in a largely hostile environment.

Keep reading >> The Quest for Progress: North Carolina 1870-1920

Learn more about North Carolina 1820-1870 in NCpedia:

Internal Improvements

Railroads

Public Education

Reconstruction

Gold Rush in North Carolina

Manufacturing

Civil War

Reconstruction

Fenn, Elizabeth Anne, and Joe A. Mobley. 2003. The way we lived in North Carolina. Chapel Hill, NC [u.a.]: Published in association with the Office of Archives and History, North Carolina Dept. of Cultural Resources, by the University of North Carolina Press.

Image Credits:

"Photograph, Accession #: H.19XX.74.1." Circa 1900. North Carolina Museum of History.

"People seeking for Gold in North Carolina". Image from Samuel Griswold Goodrich's The First Book of History for Children and Youth. Boston: Carter, Hendee, and Co., 1833. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100109381

Brose, W. and Tanner, Henry Schenck. "A New Map of Nth. Carolina with its Canals, Roads & Distances from place to place, along the Stage & Steam Boat Routes. by H. S. Tanner." Philadelphia: 1836. https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/ncmaps/id/187

Tomkins, D.A. "State Must Take Action in Good Roads." In Southern Good Roads, February 1911, p. 10. Lexington, N.C. : Southern Good Roads Pub. Co. https://archive.org/stream/southerngoodroad1911varn/southerngoodroad1911varn#page/n43/mode/1up

27 March 2019 | Anderson, Jean B.