Stars and Bars

The Stars and Bars served as the first national flag of the Confederate States of America from 4 Mar. 1861 until 1 May 1863. The name derived from the blue canton with a circle of white stars and the three red, white, and red bars in the flag's field. Early flags contain seven stars for the original seven states of the Confederacy. Later examples include 11 stars and occasionally even 12 or 13 for the border states of Missouri and Kentucky. Because of its close resemblance to the Union's Stars and Stripes, the design was dropped in 1863. Even in modern times, most native-born southerners erroneously refer to the Confederate army's post-1863 battle flag as the Stars and Bars.

The Stars and Bars served as the first national flag of the Confederate States of America from 4 Mar. 1861 until 1 May 1863. The name derived from the blue canton with a circle of white stars and the three red, white, and red bars in the flag's field. Early flags contain seven stars for the original seven states of the Confederacy. Later examples include 11 stars and occasionally even 12 or 13 for the border states of Missouri and Kentucky. Because of its close resemblance to the Union's Stars and Stripes, the design was dropped in 1863. Even in modern times, most native-born southerners erroneously refer to the Confederate army's post-1863 battle flag as the Stars and Bars.

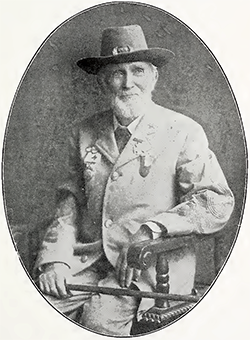

Although the flag committee had specifically requested design proposals from the public, no official credit was given at the time for the originator of the Stars and  Bars. In the early twentieth century controversy arose between two men, their families, and their home states over the question of who should receive credit for the flag's design. Maj. Orren Randolph Smith of North Carolina and Nicola Marschall of Alabama both claimed to have designed the Stars and Bars. Each man received support from his family, his home state, and local veterans and patriotic groups. Smith maintained he had submitted a model of the flag to the Confederate Provisional Congress in Montgomery in February 1861 and had flown an example of his design in Louisburg and made still another copy for a local militia company. Marschall stated he had presented several patterns, including the one adopted.

Bars. In the early twentieth century controversy arose between two men, their families, and their home states over the question of who should receive credit for the flag's design. Maj. Orren Randolph Smith of North Carolina and Nicola Marschall of Alabama both claimed to have designed the Stars and Bars. Each man received support from his family, his home state, and local veterans and patriotic groups. Smith maintained he had submitted a model of the flag to the Confederate Provisional Congress in Montgomery in February 1861 and had flown an example of his design in Louisburg and made still another copy for a local militia company. Marschall stated he had presented several patterns, including the one adopted.

Both men produced notarized affidavits to support their claims. Smith's crusade was continued by his daughter after his death in 1913, and Marschall's by his family following his death in 1917. The legislative bodies of North Carolina and Alabama each passed resolutions endorsing the flag's designer as a citizen of their state. The controversy received such attention that the United Confederate Veterans, Sons of Confederate Veterans, and Confederate Southern Memorial Association formed committees to investigate the claims of the two men. All three organizations issued statements that while there was no conclusive evidence for either party, the greater evidence supported Smith's claim. Since then, new information has given additional credence to Marschall's claim. It is quite possible that the two men submitted designs so alike that each believed he was the father of the Stars and Bars.

References:

Devereaux D. Cannon Jr., The Flags of the Confederacy: An Illustrated History (1988).

Sons of Confederate Veterans, The Stars and Bars: Report of the "Stars and Bars" Committee (1917).

Additional Resources:

"The Designer of the Stars and Bars." Sky-Land 1. No. 8. July 1914. p. 450-454. https://cdm16062.contentdm.oclc.org/u?/p249901coll37,12082

Winston, William. "The Stars and Bars: History of the First Confederate Flag." North Carolina Education 6. No. 10. June 1912. p.20. https://digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/north-carolina-education-1912-june/408232

Image Credits:

"Maj. Orren Randolph Smith" from "The Designer of the Stars and Bars" Sky-Land 1. No. 8. July 1914. p. 453. https://cdm16062.contentdm.oclc.org/u?/p249901coll37,12082

1 January 2006 | Belton, Tom