Civil Rights Movement

Part i: Introduction; Part ii: Roots of Civil Rights Activism in North Carolina; Part iii: Brown v. Board of Education and White Resistance to School Desegregation; Part iv: Integration Efforts in the Workplace, Sit-Ins, and Other Nonviolent Protests; Part v: Forced School Desegregation and the Rise of the Black Power Movement; Part vi: Continued Civil Rights Battles in the State.

Part VI: Continued Civil Rights Battles in the State

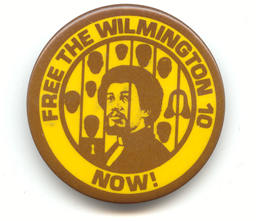

The shift in strategy after the 1960s did not alter the fundamental goals of civil rights workers. Legislation born of the movement eliminated the practice of legal segregation, but activists still fought racism and de facto segregation in North Carolina and the rest of the nation. Individuals, groups, and organizations continued that battle for social, educational, and political equality through both peaceful and nonpeaceful means. And white resistance and violence continued to greet the state's African Americans, with racially charged incidents continuing into the 1970s. One of the most notorious occurred in 1970 in Oxford, when Henry "Dickie" Marrow, a 23-year-old black veteran, was murdered by Robert Teel, a white man with KKK connections, and his sons. Teel's subsequent acquittal led to anger, violence, and unrest among the town's African American population. Similarly, a week of racial tension in Wilmington in early February 1971, rooted in dissatisfaction among black students who boycotted a public school, left two men dead and others wounded and resulted in the use of the National Guard and the imposition of a citywide curfew. A white-owned grocery store was fire-bombed, and and a year later nine black men and a white woman (nicknamed the "Wilmington Ten") were convicted of the crime. In 1980 a federal court overturned the convictions on technical grounds. Unrest was pronounced in the state following the 1971 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in the case of Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education that forced cities across the South to enact a policy of busing if necessary to achieve racial desegregation in public schools. On 3 Nov. 1979 five members of the Communist Workers Party were slain at a Greensboro anti-Klan rally. At a trial in 1980 six Klansmen were cleared of murder charges stemming from the incident. The jury's verdict set off protest demonstrations on several college campuses throughout the state.

The shift in strategy after the 1960s did not alter the fundamental goals of civil rights workers. Legislation born of the movement eliminated the practice of legal segregation, but activists still fought racism and de facto segregation in North Carolina and the rest of the nation. Individuals, groups, and organizations continued that battle for social, educational, and political equality through both peaceful and nonpeaceful means. And white resistance and violence continued to greet the state's African Americans, with racially charged incidents continuing into the 1970s. One of the most notorious occurred in 1970 in Oxford, when Henry "Dickie" Marrow, a 23-year-old black veteran, was murdered by Robert Teel, a white man with KKK connections, and his sons. Teel's subsequent acquittal led to anger, violence, and unrest among the town's African American population. Similarly, a week of racial tension in Wilmington in early February 1971, rooted in dissatisfaction among black students who boycotted a public school, left two men dead and others wounded and resulted in the use of the National Guard and the imposition of a citywide curfew. A white-owned grocery store was fire-bombed, and and a year later nine black men and a white woman (nicknamed the "Wilmington Ten") were convicted of the crime. In 1980 a federal court overturned the convictions on technical grounds. Unrest was pronounced in the state following the 1971 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in the case of Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education that forced cities across the South to enact a policy of busing if necessary to achieve racial desegregation in public schools. On 3 Nov. 1979 five members of the Communist Workers Party were slain at a Greensboro anti-Klan rally. At a trial in 1980 six Klansmen were cleared of murder charges stemming from the incident. The jury's verdict set off protest demonstrations on several college campuses throughout the state.

In 1981, for the first time in North Carolina history, a county (Moore) was split between congressional districts when the General Assembly turned to the decennial task of redrawing lines for congressional and legislative districts. The state attorney general regarded the redistricting plan as so deficient that he recommended that the General Assembly redraw the lines. Thus began a controversy with strong racial overtones that continued after the next census as well, when North Carolina gained a twelfth U.S. House seat in 1990. In 1992 Melvin L. Watt was elected to represent the new district; he and Eva M. Clayton (elected in the First Congressional District the same year) became the first black congressional representatives from the state since 1900. In 1993 the U.S. Supreme Court ordered further hearings in a case that charged that the gerrymandering of the North Carolina's Twelfth Congressional District violated the rights of white voters. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the legality of the Twelfth District's boundaries in 2001, but battles over race and representation in the drawing of North Carolina's congressional and legislative boundaries continued to rage in the early 2000s.

In addition to African Americans, other North Carolinians, including Native Americans, women's groups, people with disabilities, gays and lesbians, and AIDS/HIV patients, have fought for and continue to seek civil rights in a variety of legal and social arenas. Civil rights issues lie at the heart of several manufacturing, environmental, and political controversies in the state, as well. In 1982 opposition developed over the selection of sites for hazardous waste disposal, as environmental and civil rights activists tried unsuccessfully to block the deposit of PCB-contaminated soil in a Warren County dump. Some associated the site selection with the high proportion of African Americans in the county. Objections arose, on similar grounds, to a planned waste treatment plant to be privately built in Anson County. Later, residents of Orange, Chatham, and Wake Counties faced "not in my backyard" controversies over unwanted waste disposal sites. National publicity also surrounded a deadly fire at the Imperial Food Products chicken processing plant in Hamlet in 1991, which claimed the lives of 25 employees-19 of them single mothers. Accusations of racial discrimination were raised when it was learned that the Hamlet Fire Chief had refused help during the tragedy from the African American Dobbins Heights Volunteer Fire Department, which was minutes away and offering assistance. The owner of the plant, Emmett J. Roe, was sentenced to 20 years in prison for involuntary manslaughter for having violated numerous safety regulations.

In addition to African Americans, other North Carolinians, including Native Americans, women's groups, people with disabilities, gays and lesbians, and AIDS/HIV patients, have fought for and continue to seek civil rights in a variety of legal and social arenas. Civil rights issues lie at the heart of several manufacturing, environmental, and political controversies in the state, as well. In 1982 opposition developed over the selection of sites for hazardous waste disposal, as environmental and civil rights activists tried unsuccessfully to block the deposit of PCB-contaminated soil in a Warren County dump. Some associated the site selection with the high proportion of African Americans in the county. Objections arose, on similar grounds, to a planned waste treatment plant to be privately built in Anson County. Later, residents of Orange, Chatham, and Wake Counties faced "not in my backyard" controversies over unwanted waste disposal sites. National publicity also surrounded a deadly fire at the Imperial Food Products chicken processing plant in Hamlet in 1991, which claimed the lives of 25 employees-19 of them single mothers. Accusations of racial discrimination were raised when it was learned that the Hamlet Fire Chief had refused help during the tragedy from the African American Dobbins Heights Volunteer Fire Department, which was minutes away and offering assistance. The owner of the plant, Emmett J. Roe, was sentenced to 20 years in prison for involuntary manslaughter for having violated numerous safety regulations.

In 1986 Robeson County-long afflicted by triracial controversies involving American Indians, African Americans, and whites-received national attention when, in a bitterly debated referendum, voters narrowly supported the merger of all five of its school systems into one. The murder of Julian T. Pierce, a Lumbee Indian candidate for a judgeship, stirred accusations that he had been assassinated by white political foes. An investigation indicated that he was shot by another Indian, who committed suicide three days later. On 1 Feb. 1988 Eddie Hatcher and Timothy B. Jacobs, calling themselves "Tuscarora Indians," seized the office of the Robesonian (a Lumberton newspaper) and held the staff hostage at gunpoint for several hours in an effort to publicize the abuse of Indian civil rights in the county. In a surprise verdict, a federal jury cleared both men on hostage-taking and related charges.

References:

David S. Cecelski, Along Freedom Road: Hyde County, North Carolina, and the Fate of Black Schools in the South (1994).

William H. Chafe, Civilities and Civil Rights: Greensboro, North Carolina, and the Black Struggle for Freedom (1980).

Jeffrey J. Crow, Paul D. Escott, and Flora J. Hatley, A History of African Americans in North Carolina (2002).

Jane Elizabeth Dailey, Bryant Simon, and Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, Jumpin' Jim Crow: Southern Politics from Civil War to Civil Rights (2000).

Davison M. Douglas, Reading, Writing, and Race: The Desegregation of the Charlotte Schools (1995).

John Egerton, Speak Now against the Day: The Generation before the Civil Rights Movement in the South (1994).

Pamela Marie Emerson, A Newspaper Held Hostage: A Case Study of Terrorism and the Media (1989).

Raymond Gavins, "Behind a Veil: Black North Carolinians in the Age of Jim Crow," in Paul D. Escott, ed., W. J. Cash and the Minds of the South (1992).

Christina Greene, Our Separate Ways: Women and the Black Freedom Movement in Durham, North Carolina (2005).

Robert Rodgers Korstad, Civil Rights Unionism: Tobacco Workers and the Struggle for Democracy in the Mid-Twentieth-Century South (2003).

Waldo E. Martin Jr. and Patricia Sullivan, eds., Civil Rights in the United States (2000).

Timothy B. Tyson, Blood Done Sign My Name: A True Story (2004).

Tyson, Radio Free Dixie: Robert F. Williams and the Roots of Black Power (1999).

Image credits:

"Free the Wilmington 10 Now!" ca. 1971-1981; 4.4 cm. North Carolina Collection. Gallery Accession No: CK.999.21

Duke Yearlook. "Women's Rights Demonstration, 13 November 1989." Online at https://www.flickr.com/photos/dukeyearlook/4460729996/. Accessed 11/20/2012.

1 January 2006 | Criner, Allyson C.; Powell, William S.