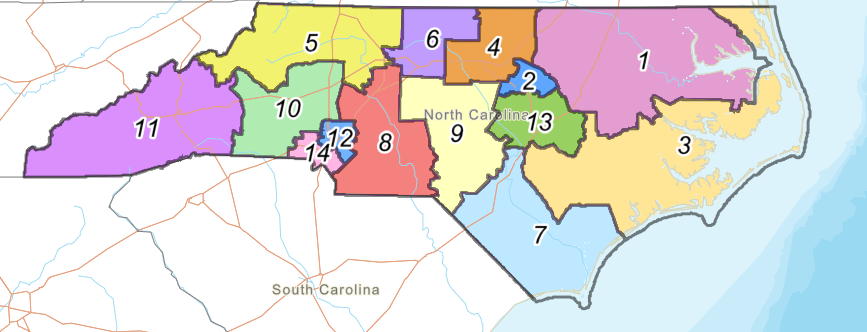

Congressional Districts

Congressional Districts in North Carolina, as in other states, have varied widely in size, shape, and number since the state ratified the U.S. Constitution in 1789. The number of congressional districts, reflecting the state's share of representatives in the U.S. House based on the decennial federal census, has ranged from as few as 7 (1865-72) to as many as 13 (1812-43, 2002- ).

Congressional Districts in North Carolina, as in other states, have varied widely in size, shape, and number since the state ratified the U.S. Constitution in 1789. The number of congressional districts, reflecting the state's share of representatives in the U.S. House based on the decennial federal census, has ranged from as few as 7 (1865-72) to as many as 13 (1812-43, 2002- ).

Drawing the boundaries of congressional districts has been the duty of the North Carolina legislature since 1789. The first districts were named after five geographic divisions: Western (now Tennessee), Yadkin, Roanoke, Edenton and New Bern, and Cape Fear. In 1790 these five were realigned, becoming the Yadkin, Centre, Roanoke, Albemarle, and Cape Fear Districts. After the first U.S. census in 1790, numbers were assigned to districts in 1792, ranging from the First District (Buncombe and four western counties) to the Tenth (Johnston County eastward to Hyde); the west-to-east pattern was reversed in 1802, then reimposed in 1852. These districts remained contiguous geographically, although both the number and exact grouping of counties often changed markedly from one census to the next.

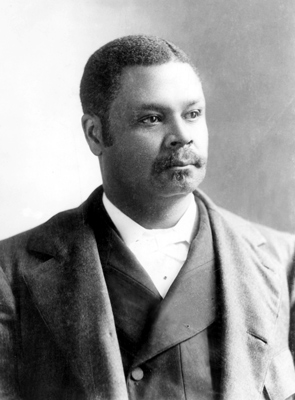

County boundaries were long considered sacrosanct dividing lines by the General Assembly's map drawers because of the legal priorities set out in Article II, sections 3(3) and 5(3), of the North Carolina Constitution. Consequently, juggling the counties to create a reasonable population balance was often complicated. In some instances, redistricting involved both political and demographic factors, such as in 1872, when the Democratic General Assembly attempted to group most of the state's Republicans into one eastern district, the so-called Black Second. Knowing a Democratic candidate could never win the district, the General Assembly selected the counties of the Black Second to isolate and neutralize eastern Republican voters, many of whom were formerly enslaved people. From 1872 to 1901 the redrawn district's African American population, nearly 66 percent of the total, elected black congressmen seven times. George White was the last of these early black congressmen in the state, representing the Second District before African American voters were largely disfranchised around 1900. Drawing district lines in favor of Democratic incumbents whenever possible was another device often employed by the General Assembly, since Democrats controlled the legislature during every postcensus session between 1872 and 1991.

After federal pressure to create two predominantly black districts in the state prompted the General Assembly to undertake a cumbersome and complicated redistricting process, the county-boundary rule was seemingly discarded in 1991. Electoral boundaries were adjusted, at least in part, to provide minorities a reasonable opportunity to elect their candidates to Congress, in compliance with the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The results were oddly shaped, long, narrow connectors between centers of black populations: a redrawn First District encompassing 9 eastern counties and parts of 19 more, stretching from Virginia to South Carolina, and a completely new Twelfth District in the Piedmont, which snaked from Durham County west and south to Mecklenburg County, mostly along the narrow "Urban Crescent" of Interstate Highway 85. The process affected adjacent districts as well; almost half of the state's 100 counties were divided, including Cumberland County, which was distributed among the First, Seventh, and Eighth Districts.

After federal pressure to create two predominantly black districts in the state prompted the General Assembly to undertake a cumbersome and complicated redistricting process, the county-boundary rule was seemingly discarded in 1991. Electoral boundaries were adjusted, at least in part, to provide minorities a reasonable opportunity to elect their candidates to Congress, in compliance with the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The results were oddly shaped, long, narrow connectors between centers of black populations: a redrawn First District encompassing 9 eastern counties and parts of 19 more, stretching from Virginia to South Carolina, and a completely new Twelfth District in the Piedmont, which snaked from Durham County west and south to Mecklenburg County, mostly along the narrow "Urban Crescent" of Interstate Highway 85. The process affected adjacent districts as well; almost half of the state's 100 counties were divided, including Cumberland County, which was distributed among the First, Seventh, and Eighth Districts.

In 1992, for the first time in nearly a century, North Carolina voters elected two black members of Congress: Melvin Watt from the new Twelfth District and Eva M. Clayton from the First District. Both Watt and Clayton were reelected several times. But the redistricting that helped lead to their election sparked a number of court battles in the 1990s. Disputes over the districts found their way to the U.S. Supreme Court four times in eight years. At the center of the conflict was Watt's Twelfth District, which was struck down as unconstitutional in 1993 and 1996. In response to these decisions, the state redrew the district twice more, in 1997 and 1998. Finally, in 2001 the Supreme Court upheld its boundaries in a narrow 5-4 decision-just in time for another round of redistricting following the 2000 U.S. census.

The census in 2000 qualified North Carolina for an additional congressional seat, bringing the total number of its congressional districts to 13 for the first time since the early nineteenth century. The new district, located in the northern Piedmont along the North Carolina-Virginia border, encompasses all of Person and Caldwell Counties and parts of Wake, Alamance, Granville, Guilford, and Rockingham Counties. Stretching from Raleigh to Greensboro, the Thirteenth District is primarily urban/suburban, with only about one-third of its voters living in rural settings or small towns. In 2002 Democrat Brad Miller was elected the first U.S. representative from the new Thirteenth District.

References:

Eric Anderson, Race and Politics in North Carolina, 1872-1901: The Black Second (1981).

John L. Cheney Jr., ed., North Carolina Government, 1585-1979: A Narrative and Statistical History (1981).

Benjamin R. Justesen, George Henry White: An Even Chance in the Race of Life (2001).

Eric Rise, ed., Congressional Redistricting in North Carolina: Reconsidering Traditional Criteria (2002).

Additional Resources:

"Report and Bill of the Committee on Congressional Districts with the Substitute Proposed." Senate and House Documents, printed for the General Assembly of North Carolina, at the session of 1852. Raleigh [N.C.]: Seaton Gales, Printer To The Legislature. 1852. 151- 162. https://digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/executive-documents-printed-for-the-general-assembly-of-north-carolina-at-the-session-of-...1852/1955623?item=2083261 (accessed December 5, 2012).

"Who Represents Me?" North Carolina General Assembly. https://www.ncleg.net/representation/WhoRepresentsMe.html (accessed December 5, 2012).

Leslie, Laura. "GOP unveils draft map of NC congressional districts." WRAL.com. July 1, 2011.

http://www.wral.com/news/state/nccapitol/story/9807863/ (accessed December 5, 2012).

North Carolina General Assembly and the N.C. Center for Geographic Information and Analysis. "North Carolina Congressional Districts." https://digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/maps-of-north-carolina-congressional-districts-1789-1960-and-state-senatorial-districts-and-apportionment-of-state-representatives-1776-1960/3690504 (accessed December 6, 2012).

Image Credits:

Original image housed by National Archives and Records Administration "George Henry White (1852-1918) represented North Carolina’s second district in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1897 to 1901."

Blacknell, Mark. "Rep. Mel Watts (D-NC)." Washington, D.C. November 13, 2006. Available from: Flickr Commons, https://www.flickr.com/photos/blacknell/296644436/ (accessed December 6, 2012).

North Carolina General Assembly. "North Carolina Congressional District Plan: Court-Ordered in 2022, to be used for the 2022 election." Map. 2022. Raleigh, N.C.: North Carolina General Assembly. https://www.ncleg.gov/Redistricting/DistrictPlanMap/C2022C (accessed May 18, 2022).

1 January 2006 | Justesen, Benjamin R.