Livestock

See also: Cattle Drives; Hog Farming; Horses; Mules; Poultry.

Livestock is a term generally synonymous with "farm animals"-domesticated animals raised by humans for food, fiber, draft, and pleasure. In America this category of animal includes cattle, sheep, pigs, goats, horses, donkeys, mules, and, by some accounts, poultry (fowl such as chickens, ducks, geese, and turkeys). Historically, domesticated animals were kept on nearly every farm and plantation. Cattle, hogs, oxen, horses, sheep, and poultry in varying numbers and combinations contributed to the subsistence of their owners.

Until after the Civil War, virtually all livestock in North Carolina was so-called native stock that was of no specific pure breed. Breeding to achieve a certain physical characteristic was simply not done. Consequently, much of the livestock had a certain nondescript look. Furthermore, some livestock were often used for dual purposes. The same cow used as a source of milk one year was driven to market the next year as beef. Its male offspring may have been castrated and trained as draft animals. This haphazardness contributed to inferior commodities, but it also produced livestock well adapted to a particular environment and suited for a wide range of purposes.

Many North Carolina farmers, like many other farmers throughout the United States, considered it unnecessary to provide shelter for or supplement the diet of their livestock. Consequently, little attention was paid to the development of meadows for hay; the sowing of oats, buckwheat, and other grain crops for feed; and the construction of barns. Because of this treatment large numbers of livestock perished during the winter. Predators, thieves, and diseases such as tick fever, carried by the cattle tick, accounted for additional losses. The tick fever problem, which killed thousands of cattle each year, was not eradicated until the 1920s.

Despite this seemingly callous attitude toward the welfare of livestock, early accounts of North Carolina claimed that many farmers owned hundreds, even thousands, of cattle, hogs, and sheep. Estate records and inventories, however, suggest that most North Carolinians owned far less livestock, probably between 6 and 16 animals. Accurately counting livestock was tricky. Until the mid-nineteenth century, most livestock roamed free, unenclosed by fences. Farmers built fences to keep livestock out of fields and gardens, not to keep them in pastures. Fencing in or corralling livestock only occurred at "cow pens" in which local cattle were collected, identified, and marked before being driven to market. There is some dispute as to whether these early pens were actually enclosures or merely open spaces where livestock could be collected and watched by herders.

Despite this seemingly callous attitude toward the welfare of livestock, early accounts of North Carolina claimed that many farmers owned hundreds, even thousands, of cattle, hogs, and sheep. Estate records and inventories, however, suggest that most North Carolinians owned far less livestock, probably between 6 and 16 animals. Accurately counting livestock was tricky. Until the mid-nineteenth century, most livestock roamed free, unenclosed by fences. Farmers built fences to keep livestock out of fields and gardens, not to keep them in pastures. Fencing in or corralling livestock only occurred at "cow pens" in which local cattle were collected, identified, and marked before being driven to market. There is some dispute as to whether these early pens were actually enclosures or merely open spaces where livestock could be collected and watched by herders.

Many early North Carolinians are depicted as self-sufficient yeoman farmers, little interested or able to engage in the larger market economy. In reality, many early North Carolinians purposefully raised livestock for the market. While data are inconsistent and at times suspect, it is apparent that North Carolina exported large numbers of livestock to other colonies (and later, states) as well as abroad. In 1733 North Carolina's governor wrote that some "fifty thousand fatt hoggs are supposed to be driven into Virginia from this Province & almost the whole number of fatted Oxen in Albemarle County with many Horses, Cows and Calves, much barreled Pork is carried into Virginia." Livestock, especially hogs and cattle, was commonly driven to cities outside of North Carolina for market. Charleston, Camden, Savannah, Petersburg, and Norfolk were regional market destinations. Between 1810 and the Civil War, tens of thousands of animals each year were driven from the state's western counties to the South Carolina and Georgia lowcountry. Livestock was also frequently driven as far north as Baltimore and Philadelphia. Although the extent of this trade is unknown it is likely that hundreds of thousands of animals were driven out of state for sale. Livestock drives continued until the 1870s, when access to railroads made them unnecessary.

North Carolina farmers and planters were slow in importing improved or pure livestock breeds into the state. Mules were one exception. These animals were virtually nonexistent in North Carolina in 1800, but by 1860 there were more than 51,000 in the state. Mules remained many farmers' primary source of farm power until after World War II. During the late antebellum period some planters did import breeding stock to begin improving extant livestock populations. Around 1841 the first shorthorn bull was introduced, but it was not until the 1870s that other breeds such as jersey and Guernsey cattle, Berkshire swine, and Shropshire sheep came into the state in any number.

After the Civil War, livestock continued to be an important aspect of agriculture in North Carolina. However, as the state's farmers increasingly turned their attention to the more profitable tobacco and cotton and improved transportation increased access to commercially available food products and textiles, fewer North Carolinians raised sheep and dairy and beef cattle. Hogs, however, continued to flourish across the state, serving as many people's only source of meat.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, interest in improving breed stock was increasing, although few North Carolina farmers had either the money or the desire to acquire purebred animals. To combat this apathy, organizations formed across the South to promote the improvement of livestock breeds. In 1911 the Animal Husbandry Section of the Association of Southern Agricultural Workers was formed, and in 1913 the Southern Cattlemen's Association organized. Breed improvement was slow; it was not until after the Depression that purebred stock began to be common around the state.

For much of the 1900s, North Carolina was known for its tobacco and cotton production. By the end of the century, however, livestock had become North Carolina's primary source of agricultural revenue. In 1964 livestock and poultry accounted for less than 30 percent of total cash receipts of all agricultural commodities. By 1994 that percentage had climbed to almost 53 percent. Much of that change was due to the meteoric rise in hog and poultry production. These two commodities, efficiently raised indoors in factory-like operations, alone accounted for 45 percent of all cash receipts. Most major hog operations are  concentrated in a belt of 22 eastern counties. Broiler production is centered in the southern Piedmont, with turkeys in the southeast and chickens in general across the central portion of the state. Although serious attempts were made to promote beef and dairy production in the state during the first half of the twentieth century, they have never been a major aspect of North Carolina agriculture. In 1994 dairy products and cattle each accounted for a mere 3 percent of all agricultural cash receipts.

concentrated in a belt of 22 eastern counties. Broiler production is centered in the southern Piedmont, with turkeys in the southeast and chickens in general across the central portion of the state. Although serious attempts were made to promote beef and dairy production in the state during the first half of the twentieth century, they have never been a major aspect of North Carolina agriculture. In 1994 dairy products and cattle each accounted for a mere 3 percent of all agricultural cash receipts.

Livestock farming in the 1990s was in a very different position than it was at the beginning of the century. Nontraditional livestock such as catfish, trout, and emus were introduced to North Carolina and quickly began to contribute to the state's agricultural economy. Other efforts are focused on preserving breeds formerly common in this state and others. The American Livestock Breed Conservancy, centered in Pittsboro, is an international organization attempting to educate the public and agriculturists about the need to preserve livestock biodiversity.

Livestock plays a major role in North Carolina's modern-day agriculture but plays little or no role in most North Carolinian's daily lives: less than 3 percent of all North Carolinians make their living from agriculture, and few of these even have contact with animals. At one time, virtually all North Carolinians had daily contact with livestock on the farm or on the streets of cities. The role of livestock has also changed and has become more focused with time. Most livestock in the early 2000s was raised entirely for human consumption, and horses had become primarily recreational animals.

References:

Cornelius O. Cathey, Agriculture in North Carolina before the Civil War (1966).

Robert S. Curtis, The History of Livestock in North Carolina (1956).

Image Credit:

Dairy Cows North Carolina State Farm, Dix Hill Aug 29, 1941 Dairy Cows North cArolina State Farm, Dix Hill Aug 29, 1941. From the Barden Collection, North Carolina State Archives, call #: N_53_16_3999. Raleigh, NC. Available from https://www.flickr.com/photos/north-carolina-state-archives/6238473724/ (accessed September 10, 2012).

Methodist Orphanage near Raleigh, NC, Farm Scene - Boys Feeding Pigs, August 1944. From the Barden Photo Collection, North Carolina State Archives, call #: N.53.16.5515, Raleigh, NC. Available from https://www.flickr.com/photos/north-carolina-state-archives/2671310278/ (accessed September 10, 2012).

Agriculture.Poultry.F3 From the H. H. Brimley Photograph Collection (Ph.C.42), North Carolina State Archives. Available from https://www.flickr.com/photos/north-carolina-state-archives/2358439149/ (accessed September 10, 2012).

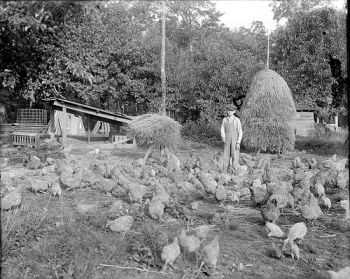

Flock of Chickens and Young Boy in Chicken Yard Prob 1900 teens Flock of chickens and a young boy in a chicken yard somewhere in North Carolina, c1900 teens. From the Albert Barden Collection, North Carolina State Archives, call #: N.53.16.4427, Raleigh, NC. Available from https://www.flickr.com/photos/north-carolina-state-archives/3328600219/ (accessed September 10, 2012).

1 January 2006 | LeCount, Charles