Improvements in Transportation: Post-American Revolution to the Civil War

"East against West: The Fight over Internal Improvements"

by John Lauritz Larson

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian. Fall 1996; Revised October 2022.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

See also: History of Transportation for K-8 Students

From the earliest days of European exploration, the land and waterways seemed to do their best to frustrate growth and movement in what was to become North Carolina. In its natural condition, the area was just not an easy place to get into or around in. Even by early antebellum times, the Outer Banks still discouraged oceangoing traffic. Obstacles like rocks, riffles, and snags slowed movement from the coast inland, and winding rivers doubled or tripled the land distance between two points. Traveling by land was nearly impossible and very inefficient. In wet weather, many roads turned to muddy bogs. In dry weather, their soft sand and dust slowed man, beast, and wagon wheel.

From the earliest days of European exploration, the land and waterways seemed to do their best to frustrate growth and movement in what was to become North Carolina. In its natural condition, the area was just not an easy place to get into or around in. Even by early antebellum times, the Outer Banks still discouraged oceangoing traffic. Obstacles like rocks, riffles, and snags slowed movement from the coast inland, and winding rivers doubled or tripled the land distance between two points. Traveling by land was nearly impossible and very inefficient. In wet weather, many roads turned to muddy bogs. In dry weather, their soft sand and dust slowed man, beast, and wagon wheel.

Soon after the American Revolution (1776–1783), some North Carolina leaders had recognized an urgent need for improving the state’s trade systems and navigation routes. As early as 1791, Governor Alexander Martin warned that other states were “opening their rivers and cutting canals,” creating valuable advantages that North Carolina did not enjoy. Others noticed that North Carolina was losing much of the trade in the state’s northeast and west to Virginia and South Carolina, because destinations in those states were easier for Tar Heels to reach than many areas in their own home state.

Sectional Split Arises

Long before the antebellum era, enslaving planters in the Coastal Plain had adapted to this discouraging transportation network. Confining their trade to the North Carolina coast and rivers up to the fall line only occasionally limited their wealth and influence. Neither did it seem to disturb their control of North Carolina’s early society and government.

At the same time, poor transportation actually seemed to aid western pioneers who struggled into the backcountry—it provided a kind of barrier from the culture of the coast and forced them to be independent and learn to take care of themselves.

A perpetual struggle for power quickly developed between these two sections. The eastern planters tried to keep control of state government in order to avoid paying higher taxes on their land and property, namely their owned enslaved people. Western residents, often led by urban merchants as well as small farmers, begged for internal improvements that would allow them to move people and goods into, around in, and out of their landlocked regions more easily.

It seemed appropriate to supporters of internal improvement, commonly known as internal improvers, for the government to promote general prosperity throughout the state. In the words of Governor Nathaniel Alexander in 1806, “nothing” was “more congenial to the spirit of... government, than the application of resources [taxes] derived from all for the benefit of all.”

Planters from the east who were serving in the General Assembly disagreed. They did not need internal improvements to market their crops, and they resented spending any government tax money that did not benefit themselves directly. Furthermore, many eastern planters worried that economic development in the western part of the state would shift population away from the Coastal Plain and threaten their longtime control of political power. Unwilling to admit their selfish concerns in public, though, these eastern politicians simply proclaimed that no government should tax and spend to improve transportation and development. They managed to convince many Tar Heel voters that such development only wasted money, favored bankers and commercial speculators, and threatened the political liberty of a free people.

Until the end of the War of 1812, eastern planters overpowered western internal improvers. The return of peace, however, began a burst of public spending for internal improvements in other states that North Carolina could not ignore. New York led the way with its famous Erie Canal. Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia all poured money into programs that opened their frontiers and improved trade.

Finally, Signs of Change

Archibald DeBow Murphey used this trend for internal improvements to start a campaign in the Old North State. Planters, he argued, were wrong to oppose government spending for roads and canals, since recent developments in England and France, as well as in other states, proved beyond doubt that public works increased public wealth for all.

It was time, he proposed, to improve navigation on the Neuse, Tar, Cape Fear, Yadkin, and Catawba rivers. He then suggested connecting these water routes with turnpike roads. He felt that this new network would lure Tar Heel farmers to market towns throughout the state and would “break the spell” that almost forced western North Carolinians to trade with Virginia and South Carolina. Murphey’s program at first was defeated, but over the next three years he won support for a state engineer, for stock subscriptions to several river improvement corporations, and for various topographical surveys.

In 1819 a devastating business panic ruined agricultural prices and left many North Carolinians unable to pay their debts. Worried that hard times would wreck support for his program of improvements, Murphey rushed to print a ninety-page Memoir of Internal Improvements, which blamed the hard times on the state’s stubborn refusal to spend money.

The basic shell of Murphey’s program was adopted by the General Assembly in 1819, but adequate funding for its projects did not soon follow. While New York and Pennsylvania, for example, spent millions of dollars apiece between 1815 and 1825, North Carolina spent barely two hundred thousand dollars performing inadequate surveys, attempting to dredge rivers and open inlets, creating turnpike roads, and building faulty canals.

Other problems stood in the way of improvements in North Carolina. Mechanical technology and advances in engineering were scarce at the time, even in states that were able to accomplish much more. And, few states faced a more discouraging landscape.

Slow Progress Leads to Bigger Changes

Experiences in other states had proven that major internal improvements were indeed very expensive. But the eastern planters in control of North Carolina’s treasury failed to commit money to seeing any plans through. They guarded against using stocks or loans that might have required increasing taxes to make future payments and caused the failure of Murphey’s program.

Friends of internal improvements even sought federal aid for major projects. But conservative Democratic-Republicans such as Nathaniel Macon saw federal aid as a violation of the U.S. Constitution and a threat to states’ rights. This political stand by a respected leader, combined with deep suspicions of modern technology and expanded commerce, convinced many North Carolinians that internal improvements were bad for white people’s freedom and independence.

Voters in the west (where more white people actually lived) reacted by demanding reapportionment—another long political struggle that eventually led to a constitutional convention.

Educator Resources:

Grades K-8: https://www.ncpedia.org/transportation-north-carolina-k-8

Image credit:

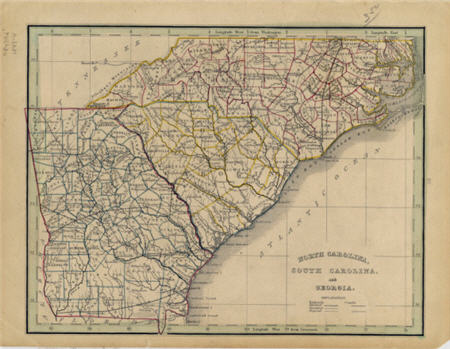

Bradford, T. G. "North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia." 1841. Owned by North Carolina State Archives. Online in NC Maps collection. Repository: North Carolina State Archives. Call no. MC.150.1841b, MARS Id: 3.3.1.1.308. Online in the UNC Libraries North Carolina Maps collection at http://dc.lib.unc.edu/u?/ncmaps,198. Accessed 12/2010.

Additional resources:

NC Department of Transportation documents in the NC Digital Collections (Government & Heritage Library and NC State Archives)

NC LIVE resources on the history of transportation in North Carolina.

Resources in libraries on the history of transportation in North Carolina [via WorldCat]

Resources on transportation in Learn NC.

Transportation in North Carolina in Documenting the American South (UNC Libraries)

1 January 1996 | Larson, John Lauritz