Constitutional Convention, 1868: "Black Caucus"

African American Political Pioneers

By Earl Ijames

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian. Fall 2008.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

During the antebellum era—the years leading up to the Civil War—North Carolina’s population of free people of color blossomed. This group included American Indians, African Americans, and multiracial Americans who were not enslaved. Many North Carolina politicians at the time favored universal suffrage (or voting rights) for free males of every race.

Along with most of the state’s enslaved population, most free people of color lived in the eastern counties. These “colored” people, as they were called then, tended to vote for eastern politicians, usually Democrats. The Piedmont and western counties tended to vote for the Whig Party. Along with pushing for better schools and internal improvements—like better roads, canals, and bridges—Whigs wanted more political power for the state’s west. Many backcountry farmers thought that the growing numbers of free people of color contributed to eastern domination of Tar Heel politics. By 1835 state leaders called for a new constitutional convention. One big issue was whether to continue letting free people of color vote. A resolution to take away their voting rights passed, 66 to 61. Abolitionists dominated the national Whig Party. However, abolitionism was not a popular political platform in many places. By 1854 the Whigs had lost power, and a new national party formed: the Republicans.

In 1860 more than one million people lived in the Tar Heel State, including about 330,000 enslaved people and more than 30,000 free people of color. When the Civil War began in 1861, North Carolina was the last southern state to secede. By 1870, the fifteenth amendment to the U.S. Constitution gave approximately 80,000 free Black men (or about 20% of the then roughly 400,000 free men, women, and children living in North Carolina) the right to vote. Congress ordered North Carolina to draw up a new state constitution. The General Assembly decided to hold a referendum in November 1867 to choose delegates to a constitutional convention to be held in early 1868. Many former Confederate leaders had not yet taken an Oath of Allegiance to the United States and were not eligible to serve. Chosen for the convention were 107 Republicans and 13 Democrats. Thirteen Black Republicans represented nineteen majority Black counties.

The members of this “Black Caucus” were not legislators, exactly. But they came together at the State Capitol in January 1868 to take part in a very important process. Let’s meet these pioneers:

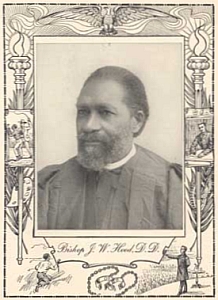

*Bishop James Walker Hood was born along the Delaware–Pennsylvania state line. Slave patrols once captured him and sold him into slavery. He escaped and returned home, becoming a third-generation minister. After the Civil War, Hood moved to North Carolina. He served as chairman of the Freedman’s Convention held in Raleigh in September 1865. He led efforts for universal education during Reconstruction. Governor William Holden appointed him assistant superintendent of the State Board of Education, in charge of Black schools, in 1870. Hood founded two historically Black colleges: Livingstone College in Rowan County and Fayetteville State University in Cumberland County.

*Bishop James Walker Hood was born along the Delaware–Pennsylvania state line. Slave patrols once captured him and sold him into slavery. He escaped and returned home, becoming a third-generation minister. After the Civil War, Hood moved to North Carolina. He served as chairman of the Freedman’s Convention held in Raleigh in September 1865. He led efforts for universal education during Reconstruction. Governor William Holden appointed him assistant superintendent of the State Board of Education, in charge of Black schools, in 1870. Hood founded two historically Black colleges: Livingstone College in Rowan County and Fayetteville State University in Cumberland County.

*Parker David Robbins (1834–1917) grew up in a community of free people of color called the Winton Triangle, along the Chowan River in Hertford and Bertie counties. The 1850 census listed Robbins—part Chowanoke American Indian and biracial—as a mechanic. He served with the U.S. Colored Troops in the Second Colored Cavalry during the Civil War. After representing Bertie County at the 1868 convention, Robbins served three terms in the North Carolina house. He patented two inventions, built and operated one of Duplin County’s first modern saw mills, built many houses in Magnolia, and owned and piloted a Cape Fear River steamboat.

*Briant Lee is perhaps least known of the group. He got as many votes as Robbins from Bertie County but was never elected to the General Assembly or Congress.

*Wilson Carey (b. 1831), a free Black farmer, represented Caswell County. Born in Virginia, Wilson moved to Caswell in 1855 and taught school. During the convention, he spoke against proposals to attract white immigrants to North Carolina: “The Negro planted the wilderness, built up the state to what it was; therefore, if anything was to be given, the Negro was entitled to it.” Carey also served in the 1875 constitutional convention dominated by Democrats. He was elected to six terms in the state house and a term in the state senate. He left Caswell County after 1889 due to Ku Klux Klan violence.

*Clinton D. Pierson represented Craven County. Craven included some of the most prosperous communities of free people of color: Harlowe, established in the 1600s; James City, named for Union General Horace James in 1862; and especially the colonial capital of New Bern.

*Henry C. Cherry, of Edgecombe County, was born in enslavement about 1836. He was trained as a carpenter and learned math, reading, and writing. Cherry is said to have worked on some of the finest antebellum homes in Tarboro. The citizens of Edgecombe reelected him twice to the state house. By 1870 Cherry owned one thousand dollars in real property and two hundred dollars in personal property. His two daughters were rumored to be among the most beautiful women of their day. One married Congressman Henry Plummer Cheatham, of Granville County, the founder of the Oxford Colored Orphanage. The other married the state’s last Black Republican congressman (and a state legislator), George H. White, a Howard University lawyer whose time in Congress ended the Reconstruction era in 1901. In 1894 Cheatham and White vied for the same congressional seat.

*Henry C. Cherry, of Edgecombe County, was born in enslavement about 1836. He was trained as a carpenter and learned math, reading, and writing. Cherry is said to have worked on some of the finest antebellum homes in Tarboro. The citizens of Edgecombe reelected him twice to the state house. By 1870 Cherry owned one thousand dollars in real property and two hundred dollars in personal property. His two daughters were rumored to be among the most beautiful women of their day. One married Congressman Henry Plummer Cheatham, of Granville County, the founder of the Oxford Colored Orphanage. The other married the state’s last Black Republican congressman (and a state legislator), George H. White, a Howard University lawyer whose time in Congress ended the Reconstruction era in 1901. In 1894 Cheatham and White vied for the same congressional seat.

*John Hendrick Williamson—born in enslavement in Covington, Georgia, in 1844—moved to Louisburg in 1858. He served as a delegate to the Republican National Conventions of 1872, 1884, and 1888. As secretary of the N.C. Industrial Association during the 1880s, Williamson founded and edited two newspapers: the Raleigh Banner and the North Carolina Gazette.

*Cuffie Mayo (1803–1896) was born free in Virginia. He moved across the state line to Granville County and worked as a blacksmith and a painter. He was the only Black Republican to represent the county with the largest number of enslaved people in the state at the 1868 convention. Mayo was later elected to two legislative sessions. By 1870 he had six hundred dollars in real property and two hundred dollars in personal property.

*Henry Eppes (1830–1917) was born enslaved in Halifax County. He was literate and worked as a brick mason and plasterer. After serving in the 1868 convention, Eppes represented his county for six terms as a state senator. He also served as a delegate to the 1872 Republican National Convention and became an ordained Methodist minister.

*W. T. J. Hayes also represented Halifax County. Like Eppes, he was literate while still enslaved. After the convention, however, Hayes served only in the General Assembly of 1869. After the defeat of an integration and equal facilities bill for education, he proposed flying the flags at the State Capitol at half mast to signal the “death of all weak-kneed Republicans.”

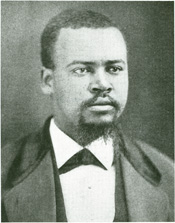

*John Adams Hyman (1840–1891) was born enslaved in Warren County, the center of the state’s “black belt.” After the 1868 convention, Hyman served four terms as a state senator. He is most noted, however, as the Tar Heel State’s first Black congressman, serving in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1875 and 1876. Becoming disillusioned with the rapid return to power of former Confederates, especially after the state’s 1875 constitutional convention, Hyman moved to Washington, D.C.

*John Adams Hyman (1840–1891) was born enslaved in Warren County, the center of the state’s “black belt.” After the 1868 convention, Hyman served four terms as a state senator. He is most noted, however, as the Tar Heel State’s first Black congressman, serving in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1875 and 1876. Becoming disillusioned with the rapid return to power of former Confederates, especially after the state’s 1875 constitutional convention, Hyman moved to Washington, D.C.

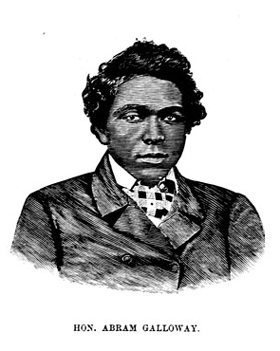

*Abraham Galloway (1837-1870) was hailed as a hero by freedmen after the Civil War. In 1857 twenty-year-old Abraham Galloway had hired himself out as a brick mason, paying his owner fifteen dollars a month. He escaped from slavery by hiding in a turpentine barrel on a ship bound from Wilmington to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The son of an Irish seaman who captained a U.S. government vessel and an enslaved woman from New Hanover County, Galloway would become an important African American leader. He reportedly visited the White House and was recruited by President Abraham Lincoln to become a Union spy. He mysteriously orchestrated events at the Battle of New Bern in March 1862. The next year, he recruited enslaved men and free people of color in North Carolina for the new “African Brigade,” which became part of the U.S. Colored Troops.

Known by the Democrats as a “radical” Republican, he wanted “owners of large estates taxed at one dollar per acre in order that the land might be sold by sheriffs and the opportunity given the Negroes to buy land.” He also favored giving women the vote. Many former Confederates thought of Galloway as “uppity” because he carried a pistol and demanded that they no longer address formerly enslaved people in derogative terms. Galloway mysteriously died a young man in 1870, shortly after serving his second term as a state senator. According to the Christian Recorder newspaper, more than six thousand mourners attended his funeral, “the largest ever known in this state.” His death was so sudden, Galloway’s wife and children were unable to travel from New Bern to Wilmington to pay their last respects.

*James Henry Harris (1832–1891) seems to be known as the most prominent Black Republican at the 1868 convention. Born free near Creedmoor in Granville County, he worked as a furniture upholsterer as a teenager. Harris operated shops in Raleigh on Fayetteville Street and up the plank road in Warren County. When laws governing free persons of color became more stringent, he moved to Oberlin, Ohio. Harris toured northern states and Canada lecturing on experiences in North Carolina.

*James Henry Harris (1832–1891) seems to be known as the most prominent Black Republican at the 1868 convention. Born free near Creedmoor in Granville County, he worked as a furniture upholsterer as a teenager. Harris operated shops in Raleigh on Fayetteville Street and up the plank road in Warren County. When laws governing free persons of color became more stringent, he moved to Oberlin, Ohio. Harris toured northern states and Canada lecturing on experiences in North Carolina.

When the Civil War began, he was teaching in the African nation of Liberia and the British colony of Sierra Leone. In 1862 he returned to the United States. By 1863 he had moved his family to Terre Haute, Indiana, where many free Black North Carolinians had migrated. Indiana Governor Levi Morton asked Harris to raise a regiment of U.S. Colored Troops. After the war, Harris returned to the Tar Heel State and became a go-between for Governor Holden and the freedmen. In addition to being a Wake County delegate to the 1868 convention, Harris served on Raleigh’s city council and was a leader for the School for the Deaf and the 1865 Freedmen’s Convention. He served four terms in the state legislature. By 1870, he had more than four thousand dollars in property. By 1880, Harris had started and edited one of the state’s most prominent newspapers, the North Carolina Republican, whose slogan was “Firm in the Right.”

These Black Republicans helped open one of the most spirited and contentious eras in North Carolina’s history. Their service inspired many others, especially formerly enslaved people, to seek a better life. Despite opposition, the 1868 delegates passed resolutions prohibiting slavery. A uniform public school system was established, along with universal male suffrage. These men helped lay the groundwork for all Tar Heel citizens’ liberties and prosperity. Between the 1868 constitutional convention and 1901, when White left Congress, ninety-seven Black Republican state legislators and twenty-seven Black United States congressmen served North Carolina. During the late 1890s, Democrats took control from the Republicans. By 1901, Black North Carolinians had been disenfranchised—again.

Image Credits

[Picture of James Walker Hood]. 1902?. Craven County Digital History Exhibit. New Bern-Craven County Public Library, 400 Johnson Street, New Bern, NC 28560.

Portrait of Parker David Robbins. 1865. Painting. NC Museum of History, Accession number 1976.11.2. Accessed Apr. 9, 2024. https://collections.ncdcr.gov/mDetail.aspx?rID=1976.11.2&db=objects&dir=MOH MUSEUMOFHISTORY.

John Adams Hyman. National Archives and Records Administration.

Engraved Portrait of Abraham Galloway. 1872. Engraving. In Underground Railroadby William Still, 150-151. Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1872. Wikimedia Commons. Accessed Apr. 9, 2024. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Galloway_Abraham.jpg.

1 January 2008 | Ijames, Earl