Agriculture at the State Fair

by RoAnn Bishop

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian. Fall 2002.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

Agriculture lies at the heart of the North Carolina State Fair. You can tell that by the many varieties of livestock, produce, and farm equipment exhibited at the annual autumn event. From grand champion beef cattle and blue-ribbon vegetables to antique tractors and butter sculptures, if it’s from the farm, you’ll find it at the State Fair.

Traditionally, North Carolina has been a land of farmers. From colonial times to the early 1900s, most North Carolinians made their living from the soil, growing the crops and raising the animals they needed to supply food and clothing for themselves and their families. In the 1840s and 1850s, rising crop prices and railroad construction made some farmers want to grow more crops to sell at market. In this period, some agricultural societies formed, and a few farm journals and almanacs were published that told farmers how to use new scientific farming methods to increase their production and their profits.

Traditionally, North Carolina has been a land of farmers. From colonial times to the early 1900s, most North Carolinians made their living from the soil, growing the crops and raising the animals they needed to supply food and clothing for themselves and their families. In the 1840s and 1850s, rising crop prices and railroad construction made some farmers want to grow more crops to sell at market. In this period, some agricultural societies formed, and a few farm journals and almanacs were published that told farmers how to use new scientific farming methods to increase their production and their profits.

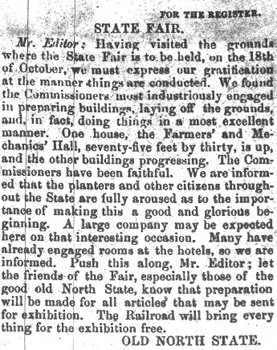

During this time, the seeds of the North Carolina State Fair were sown. The North Carolina State Agricultural Society had formed in Raleigh in 1818 to promote better farming practices. During its second year, the society decided to sponsor a “Cattle Show and Exhibition of Domestic Manufactures and a Ploughing Match, to take place in Raleigh, in the month of October, annually.” But poor planning and publicity delayed the event. Also, low farm prices and the lack of markets soon caused farm reformers to lose interest in the society. Then, spurred by a wave of internal improvements in North Carolina during the 1840s and 1850s, the Agricultural Society reorganized in 1852, and at the top of its list of things to do was to sponsor a State Fair.

The first “State Exposition” took place in October 1853 on a sixteen-acre site about ten blocks east of the Capitol. It lasted four days and drew an estimated four thousand people. Admission was twenty-five cents per person, fifty cents for buggies, and a dollar for carriages. Boats brought some display materials up the “Blackwater” (possibly the Neuse River), and other materials and livestock arrived by rail. All were transported for free. Premiums of ten dollars and five dollars for first and second places were offered in most categories of competition, and the runners-up received certificates.

Eight State Fairs took place before the Civil War began in 1861. Afterward, many North Carolina farms and plantations lay in ruins. Gradually, North Carolina’s agriculture recovered, manufacturing increased, and the fair reopened. By 1884 state leaders could plan to stage the “Great North Carolina Exposition” to show “the variety and magnificence of the products and resources of North Carolina.” This State Fair remained open for a month, at the second of Raleigh’s three fair sites: on Hillsborough Street across from present-day North Carolina State University.

Eight State Fairs took place before the Civil War began in 1861. Afterward, many North Carolina farms and plantations lay in ruins. Gradually, North Carolina’s agriculture recovered, manufacturing increased, and the fair reopened. By 1884 state leaders could plan to stage the “Great North Carolina Exposition” to show “the variety and magnificence of the products and resources of North Carolina.” This State Fair remained open for a month, at the second of Raleigh’s three fair sites: on Hillsborough Street across from present-day North Carolina State University.

The opening of the North Carolina College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts (now North Carolina State University) in 1889 came at a time when the state’s agriculture needed a boost. The farm tenancy and crop lien systems that arose after the Civil War had plunged many farm families into poverty. Under the farm tenancy system, farmers rented land, paying either cash or a share of a “cash” crop, such as cotton or tobacco. Under the crop lien system, farmers also promised part of their crops to a local merchant as payment for goods received on credit during the year. In a bad farming year, a farmer could end up owing more money than his crops had made. Unhappy farmers organized to push for agricultural reforms. The Farmer’s Alliance, one of the reform groups, helped to establish the college. The college, in turn, helped farmers by making new agricultural research available and by eventually providing extension services that sent faculty across the state to teach and consult with farmers. The college’s agricultural education efforts appeared at the State Fair in the form of exhibits and demonstrations.

By 1895 the State Fair had become the main annual event for rural North Carolinians. Some folks traveled for days to get to Raleigh, so that they could compare the products of their farms against others in the state and learn about new agricultural methods, machinery, and animal breeds. The main attraction at the 1895 State Fair was chicken incubators. Amazed spectators watched as up to two hundred eggs hatched at one time. Today, poultry is North Carolina’s top moneymaking agricultural industry.

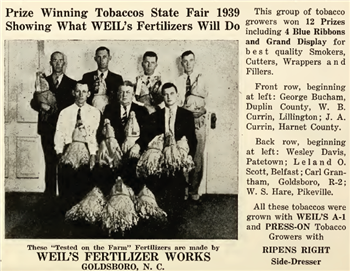

North Carolina’s farmers, however, did not make much money until World War I increased the demand for their agricultural goods. By the time the soldiers returned from Europe in 1919, high cotton and tobacco prices had brought a new prosperity. But it was short-lived. An agricultural depression in the 1920s sent crop prices down, forcing more and more farm families into tenancy (renting land). Many people had to quit farming and take factory jobs in cities, increasing a late-nineteenth-century trend from agricultural to industrial employment. Also, the cotton boll weevil infestation reached North Carolina in the late 1920s and destroyed many cotton crops. Farmers who clung to their way of life largely stopped growing cotton and switched to tobacco or diversified (mixed) farming. Exhibits at the State Fair reflected these changes.

North Carolina’s farmers, however, did not make much money until World War I increased the demand for their agricultural goods. By the time the soldiers returned from Europe in 1919, high cotton and tobacco prices had brought a new prosperity. But it was short-lived. An agricultural depression in the 1920s sent crop prices down, forcing more and more farm families into tenancy (renting land). Many people had to quit farming and take factory jobs in cities, increasing a late-nineteenth-century trend from agricultural to industrial employment. Also, the cotton boll weevil infestation reached North Carolina in the late 1920s and destroyed many cotton crops. Farmers who clung to their way of life largely stopped growing cotton and switched to tobacco or diversified (mixed) farming. Exhibits at the State Fair reflected these changes.

Meanwhile, important new farming alternatives—dairying and truck farming (growing fresh fruits and vegetables for market)—emerged in the 1920s and 1930s as increasing urban populations demanded fresh dairy products and produce. Today, you can see some early dairying equipment at the State Fair’s Antique Farm Machinery Museum, located across from the Village of Yesteryear.

Federal relief programs helped farm families survive through the Great Depression of the 1930s, but changes in the traditional way of life had begun. Automobiles, electric lights, and telephones had already altered farm life, and World War II technology brought more changes through new chemicals, tools, and machinery in the 1940s and 1950s. Cotton and tobacco production limits, the mechanization of farming, and the increased use of pesticides reduced the amount of land under cultivation and the number of laborers in the fields. By the mid-1900s, family farms were becoming fast, efficient commercial operations called “agribusinesses.” And many farmers were hanging up their hats.

Since World War II, diversification has helped to expand and improve North Carolina agriculture, as have ongoing research and ever-changing technology. In 1968, a year before the Apollo 11 moon landing, an article in the State magazine predicted that space-age technology would “command equal interest with agriculture” at the State Fair. In the past few years, computer exhibits and high-tech displays, such as the BioFrontiers exhibit at the 2001 State Fair, have indeed become part of the fair’s attractions. But, instead of competing, technology has worked alongside agriculture to enhance it and to explore new farming frontiers.

In 2003 the North Carolina State Fair celebrated its 150th anniversary.

At the time of this article’s publication, RoAnn Bishop worked as an associate curator at the North Carolina Museum of History.

References and additional resources:

Blue Ribbon Memories: Your History of the North Carolina State Fair [in beta]. http://statefair.ncdcr.gov

Graham, Jim. The Sodfather: A Friend of Agriculture in North Carolina. 1998

North Carolina State Fair Web site: http://www.ncstatefair.org

McLaurin, Melton Alonza. 2003. The North Carolina State Fair: the first 150 years. Raleigh, [N.C.]: Office of Archives and History, N.C. Dept. of Cultural Resources.

1 January 2002 | Bishop, RoAnn