Freedom Rallies: Williamston, N.C., 1963

Freedom Rallies: Williamston, N.C., 1963

By Michael Hill

Research Branch, NC Office of Archives and History, 2010

https://www.dncr.nc.gov/about-us/history/division-historical-resources/nc-highway-historical-marker-program

Mass meetings at Green Memorial Church for 32 days, June-July 1963, & nonviolent marches, led to the desegregation of local public facilities.

Williamston, seat of Martin County on the Roanoke River, was a “hotspot” of the civil rights movement and Green Memorial Church was the epicenter. David C. Carter, a professor at Auburn University, wrote about Williamston while a doctoral candidate at Duke University: “If a ‘Second Reconstruction’ failed to topple the barriers to racial equality in Martin County, the experience of building a genuine community in protest and the dramatic personal transformations that resulted from participation in the Williamston Freedom Movement still remain to inform the struggles of a future generation in a Third Reconstruction.” Those in the movement “demanded basic human rights” and thereby the democratic transformation of an inherently unfair system.

“Almost invariably,” according to Carter, protests originated at Green Memorial, a Disciples of Christ church rooted in the Holiness tradition. Founded in 1897 as River Hill, the church took its name in 1933 from its second pastor John R. Green. Discontent simmered after the acquittal of white men charged in 1957 with the murder of a local black man. Protesters, keenly aware of civil rights protests across the South, made it their goal to desegregate schools and the public library. Organizing the efforts were a local woman, Sarah Small, and Golden Frinks (1920-2004) of Edenton, a friend of Martin Luther King. As the protests continued, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference held biweekly nonviolence training sessions at the church.

Remarkably, protests continued for 32 consecutive days beginning on June 30, 1963, involving as many as 400 people, many of them children and teenagers, singing and praying, before marching uptown, about a half-mile to the courthouse. State troopers and local deputies kept close watch over the activity. Rallies were suspended temporarily after the Governor’s office organized interracial meetings but resumed in the fall, when 12 white ministers and seminarians from Boston joined the effort. The Ku Klux Klan organized rallies outside town.

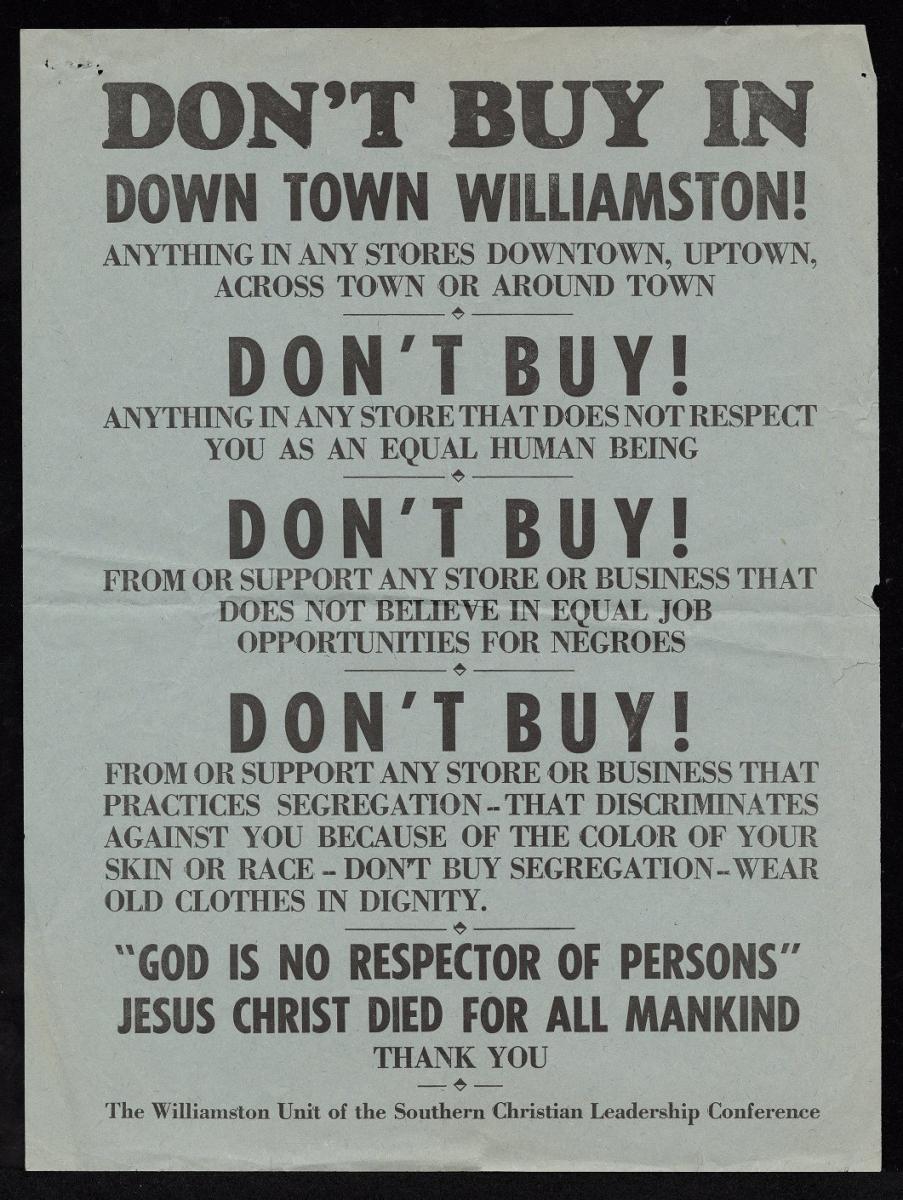

In contrast to the summer rallies, which were nonviolent, protesters engaged one evening in bottle-throwing and some recall use by authorities of electrified cattle prods. A boycott of local businesses was short-lived. Town officials instituted use of parade permits but notably took gradual steps to desegregate facilities with the exception of schools. Kennedy’s assassination coincided with the end of direct action and protesters witnessed the passage by Congress of the Civil Rights Act on July 2, 1964, ending legal barriers to public facilities.

References:

Carter, David C. “The Williamston Freedom Movement: Civil Rights at the Grass Roots in Eastern North Carolina,” North Carolina Historical Review (January 1999): 1-42. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23522168 (Accessed May 11, 2022).

Carter, David C. 2014. The music has gone out of the movement: civil rights and the Johnson administration, 1965-1968. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Smith, Amanda Hilliard. 2014. The Williamston freedom movement: a North Carolina town's struggle for civil rights, 1957 - 1970. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

Waynick, Capus M. 1964. North Carolina and the Negro. Raleigh: North Carolina Mayors' Co-operating Committee.

Image Credits:

Southern Christian Leadership Conference. "Don't Buy in Down Town Williamston!" Poster image. April 1964. Item 421.27.1, East Carolina University Digital Collections. http://digital.lib.ecu.edu/27094 (accessed April 9, 2016).

8 April 2016 | Hill, Michael