Civil Rights Movement

Part i: Introduction; Part ii: Roots of Civil Rights Activism in North Carolina; Part iii: Brown v. Board of Education and White Resistance to School Desegregation; Part iv: Integration Efforts in the Workplace, Sit-Ins, and Other Nonviolent Protests; Part v: Forced School Desegregation and the Rise of the Black Power Movement; Part vi: Continued Civil Rights Battles in the State.

Part IV: Integration Efforts in the Workplace, Sit-Ins, and Other Nonviolent Protests

Progress toward school desegregation was painfully slow, but schools were not the only battle front in the civil rights movement in North Carolina. Integration of the workplace was, for example, another significant focus of the movement. In 1957 delegates from the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), a Quaker organization dedicated to social justice, successfully pressured and encouraged textile manufacturers to hire black employees in one of their North Carolina factories. Though the African Americans were placed in clerical positions, the move laid a foundation for future advances. In 1958 the AFSC reported that it had assisted in the appointment of a black supervisor at a large textile mill in Greensboro. In 1959 a textile manufacturer in High Point agreed to hire five black men as production workers. Some white workers left the mill when the blacks started, but the mill owner remained steadfast and the experiment succeeded. The exclusion of blacks remained widespread, however, until the pressure of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 forced companies to relent. Soon after the act went into effect, Southerland Mills in Mebane hired some of the state's first black female textile workers.

Civil rights activists fought racism in their communities by standing up for themselves and using all the tools and tactics of the national civil rights movement; civil disobedience, strikes, picket lines, and economic boycotts (methods also utilized by the labor movement) were hallmarks of the 1950s and 1960s. The use of nonviolent protests in such forms as marches and sit-ins led to important progress in the integration of North Carolina's theaters, hotels, and restaurants by 1963. That year the General Assembly voted to desegregate the National Guard. Municipal cemeteries were eventually integrated as well.

Although sit-ins had occasionally been staged during labor strikes and other civil actions earlier on, they were not a widespread form of protest until the 1960s. Sit-ins were attempted in North Carolina as early as 1943 without publicity. In 1957 seven African American students led by the Reverend Douglas E. Moore went into the Royal Ice Cream Company shop in Durham using a whites-only entrance. They took seats inside, only to be arrested and fined $25.00 apiece.

A sea change for the sit-in movement occurred in Greensboro on 1 Feb. 1960. Four black students from the North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University walked into an F. W. Woolworth's in downtown Greensboro at about 4:30 in the afternoon. Ezell A. Blair (now Jibreel Khazan), Franklin E. McCain, Joseph A. McNeil, and David L. Richmond made various purchases from different departments of the store, thereby becoming paying customers. They then proceeded to Woolworth's luncheonette counter and requested to be served. In reply they were told that blacks were not served in that establishment, but they could order food at a stand nearby. As black workers behind the counter shook their heads, calling the boys foolish, and white workers asked the four to leave, the youths remained seated at the counter until the store was closed. The next day the number of protesters increased to 15, which became about 150 on the third day and then mushroomed to nearly 1,000 the day after that. The protests soon spread to other downtown lunch counters. The nonviolent protesters, including area white students as well, augmented their sit-ins with economic boycotts. Finally, on 25 July 1960, it was announced that Woolworth's, Kress, and Meyers lunch counters would henceforth serve blacks.

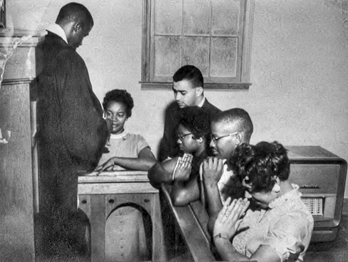

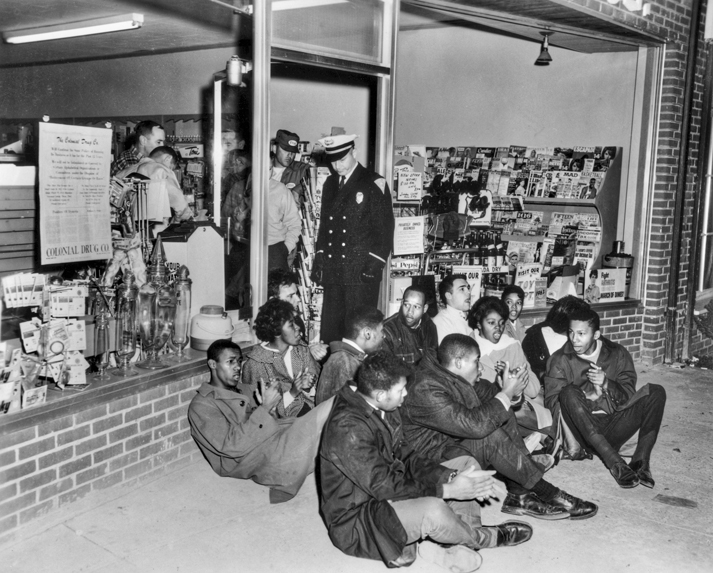

After the initial Greensboro sit-in, other such protests followed around the state and the South: in the short term, a week later they spread to Durham and Winston-Salem and then to communities in South Carolina, Florida, Virginia, and Tennessee, while, in the long-term, they remained an effective tactic for many years. Charlotte and Salisbury both saw successful sit-in movements, and in 1964 sit-ins came to Brady's Restaurant and the Colonial Drug Store, two popular eateries in Chapel Hill. These events heralded the collective entrance of young people into the civil rights movement as high school and college students participated en masse in sit-ins around the country. Organizations such as CORE held workshops for sit-in planners, and protesters always adhered to certain guidelines. For example, they faced straight ahead at the counter, dressed well, generally did not talk among themselves, and always remained calm and nonviolent.

In April 1960 a new organization emerged from the North Carolina sit-ins. Ella Baker, who by then worked for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), invited a number of southern university students, some of whom had participated in sit-ins, to Shaw University in Raleigh. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) grew out of these meetings, with the purpose of coordinating the use of nonviolent direct action against segregation and other forms of racism. Over the course of the 1960s, SNCC's importance in local efforts increased with its growing profile and significance in the national movement, in which it played a leading role in the Freedom Rides, the Mississippi Freedom Summer, and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

Community activism continued in North Carolina, often without attention from the national press, and a number of local black leaders formed movements within their own communities. Golden Frinks, a member of the NAACP and SCLC, was one of the most important civil rights organizers in eastern North Carolina in the 1960s. Frinks was a leader in the 1961-62 Edenton Movement, a campaign distinguished by its location and supporters. Unlike most of the prominent civil rights protests up to that point, the Edenton Movement took place in an isolated, mostly rural area rather than a city. Its leadership came not from a college-educated or middle-class population, but from poor, uneducated people. Frinks used the strategies of civil disobedience, picket lines, slowdowns, strikes, and boycotts developed in Edenton, the small eastern North Carolina town where the movement began, to drive the Williamston Freedom Movement that included 32 straight days of demonstrations and sit-ins in the nearby town of that name. Activists also staged an economic boycott of downtown businesses and attempted to enroll black students at the local white high school. Their efforts won important concessions. The degrading "colored/white" signs were removed from public places, and hospitals, libraries, and schools were integrated.

In 1962 and 1963 a coalition of SNCC, the SCLC, CORE, and the NAACP-called the Council of Federated Organizations-was formed to register black voters all over the South. Several local organizations also participated. In North Carolina, the Halifax County Voters Movement exemplified the organized efforts of blacks to shape politics in their communities. The organization's aims included increased black voter registration, more blacks running for office, and improved relations with white officials. Similar groups soon appeared in nearby Bertie and Northampton Counties. Meanwhile, demands for equal political participation resounded throughout the nation, pressuring President Lyndon B. Johnson to support two important pieces of legislation aimed at securing full civil and voting rights for African Americans. Both the national Civil Rights Act of 1964 (which included policies such as affirmative action) and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 addressed the need for black voter registration. The latter act-coming in the wake of the dramatic, and in many ways climactic, Selma-to-Montgomery March of 21-25 Mar. 1965-is generally considered the culmination of one phase of the civil rights movement, as the coalition of civil rights organizations of the early 1960s soon began to unravel as a result of disagreements over strategies-including white involvement in the movement-and personalities.

Keep reading > Part V: Forced School Desegregation and the Rise of the Black Power Movement

References:

David S. Cecelski, Along Freedom Road: Hyde County, North Carolina, and the Fate of Black Schools in the South (1994).

William H. Chafe, Civilities and Civil Rights: Greensboro, North Carolina, and the Black Struggle for Freedom (1980).

Jeffrey J. Crow, Paul D. Escott, and Flora J. Hatley, A History of African Americans in North Carolina (2002).

Jane Elizabeth Dailey, Bryant Simon, and Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, Jumpin' Jim Crow: Southern Politics from Civil War to Civil Rights (2000).

Davison M. Douglas, Reading, Writing, and Race: The Desegregation of the Charlotte Schools (1995).

John Egerton, Speak Now against the Day: The Generation before the Civil Rights Movement in the South (1994).

Pamela Marie Emerson, A Newspaper Held Hostage: A Case Study of Terrorism and the Media (1989).

Raymond Gavins, "Behind a Veil: Black North Carolinians in the Age of Jim Crow," in Paul D. Escott, ed., W. J. Cash and the Minds of the South (1992).

Christina Greene, Our Separate Ways: Women and the Black Freedom Movement in Durham, North Carolina (2005).

Robert Rodgers Korstad, Civil Rights Unionism: Tobacco Workers and the Struggle for Democracy in the Mid-Twentieth-Century South (2003).

Waldo E. Martin Jr. and Patricia Sullivan, eds., Civil Rights in the United States (2000).

Timothy B. Tyson, Blood Done Sign My Name: A True Story (2004).

Tyson, Radio Free Dixie: Robert F. Williams and the Roots of Black Power (1999).

1 January 2006 | Criner, Allyson C.; Powell, William S.