Exploration, European

See also: Amadas and Barlowe Expedition; De Soto Expedition; Lederer Expedition; Lost Colony; Pardo Expeditions; Roanoke Voyages; Verrazano Expedition; Art of John White (from Tar Heel Junior Historian)

Part i: Introduction; Part ii: Initial European Expeditions; Part iii: Sir Walter Raleigh and the Arrival of the English; Part iv: Seventeenth-Century Explorers; Part v: References

Part III: Sir Walter Raleigh and the Arrival of the English

Queen Elizabeth and her subjects became troubled by Spain's growing wealth provided by its New World colonies and believed that this advantage would inevitably undermine England's cultural identity (particularly its national Protestant faith) and economic independence. In an effort to slow their enemy's progress, Englishmen such as Francis Drake, Richard Grenville, and Thomas Cavendish captured Spanish treasure ships as well as attacked and destroyed Spain's American outposts. The amazing treasures acquired by these actions-gold, silver, jewels, spices, and lumber-excited people of all classes of English society and inspired in them a deep curiosity and an almost manic desire to see and obtain more of America's riches.

Sir Walter Raleigh assumed leadership of England's colonization movement in 1583 after the death of his half brother Sir Humphrey Gilbert, who had convinced the queen that her only recourse was to defeat Spain by aggressively exploring and settling the New World. Raleigh's determination was rewarded in March 1584, when Elizabeth granted a charter allowing him to organize an expedition for the purpose of finding suitable colonization sites in North America.

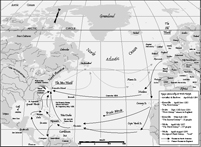

On 27 Apr. 1584 Capts. Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe set sail from Plymouth to scout for a location for Raleigh's proposed colony. On 4 July 1584 they sighted the North American coast and sailed north for 120 miles before finding a suitable inlet that their ships could enter. After anchoring inside the inlet, they landed on a nearby island and claimed the territory for their queen. On this island, either present-day Ocracoke or Hatteras, they made first contact with the natives and began to trade with them. After several days, Barlowe and seven companions took a trip to these natives' home. Barlowe noted that they traveled "twenty miles into the river that runs toward Skicoak, which river they call Occam; and the evening following we came to an island, which they call Roanoke, distant from the harbor by which we entered seven leagues." At Roanoke they were entertained by the Indians and obtained much information about the country. But this was the extent of their explorations. Returning to their ships, they set sail for England, which they reached in September 1584.

In June 1585 Sir Richard Grenville arrived with 107 colonists aboard two ships off Wocokon (modern Ocracoke). From there, the Croatoan Indian Manteo was dispatched to the mainland to send word of the arrival of the Englishmen to King Wingina. Not wishing to waste time, Grenville and several of his men left Wocokon in two boats for an eight-day exploration of the southern reaches of Pamlico Sound. They visited several Indian towns, including Pomeiok, Aquascogoc, and Secotan; they were "well entertained there [at Secotan]" by the natives. Grenville also discovered a "great lake" that the Indians called "Paquipe."

On their return to Ocracoke, the Englishmen moved up the Outer Banks and anchored off "Hatorask" (modern Hatteras Island). Grenville deposited his colonists on Roanoke Island before setting sail for England on 25 Aug. 1585. Under the command of Ralph Lane, the colonists who remained engaged in extensive explorations over the next year. Their ramblings took them north to the Chesapeake Bay and up the Chowan River to the junction of the Meherrin and Nottoway Rivers.

Perhaps this group's best-known exploration was up the Moratok (Roanoke) River. With 40 men in two boats, Lane and his party spent three days rowing against the strong current of the Roanoke, covering what he estimated to be "one hundred sixty miles from home." The Indians along the river had retreated inland, carrying their food with them, so the Englishmen were unable to obtain supplies as they traveled deeper into the interior. The group continued up the river but still found no prospect of finding food. After Lane's men were attacked by hostile Indians, they decided to return downstream. They made the mouth of the Roanoke after one day's travel and spent the day before Easter waiting for the winds to lay so they could cross Albemarle Sound, stopping at some fish weirs for food. They returned to Roanoke Island the day after Easter in 1586. Then, fearing that they had been abandoned by their countrymen, Lane's colonists took the opportunity of Sir Francis Drake's arrival to sail home.

They returned to England in July 1586. Besides the valuable practical information they had gathered, which appeared on new maps of the area, this expedition is significant because of the work of two of its members: Thomas Harriot, who published a book about the lands explored; and John White, whose watercolor paintings and sketches were the first extensive images of American flora, fauna, and Indian culture seen by Europeans.

The next colonists to arrive on the Outer Banks were under the command of White, who was a strong advocate of settling the region. This group constituted the famed "Lost Colony," and any record of explorations conducted by its members disappeared with them. In 1602 Samuel Mace led an expedition to America financed by Raleigh. One of its missions was to seek information on the missing colonists. Mace and his men landed along the North Carolina coast somewhere between Cape Fear and Cape Lookout, where they established a base from which to search for medicinal plants and herbs. They remained in their camp about a month before sailing up the coast toward Roanoke. A severe storm broke before they could land on Hatorask, and Mace decided to head for England.

Raleigh's Lost Colony continued to have an impact on the exploration of present-day North Carolina for several years. In 1608 Capt. John Smith dispatched two unidentified individuals south on a reconnaissance mission from Jamestown. Evidence suggests that they may have sailed as far as the Neuse River. Smith subsequently sent other groups south, but it is uncertain whether they reached North Carolina.

Keep reading > Part IV: Seventeenth-Century Explorers ![]()

Additional Resources:

National Park Service. "The Roanoke Voyages." National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. https://www.nps.gov/fora/learn/kidsyouth/voyage.htm (accessed February 1, 2019).

Hariot, Thomas and Paul Royster, editor. "A Brief and True Report of the New Found Land of Virgina (1588)." Electronic Texts in American Studies 20 (1588). http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1020&context=etas (accessed February 1, 2019).

Tyler, Lyon Gardiner, 1853-1935: The cradle of the republic : Jamestown and James River (1906).

Image Credit:

Roanoke Voyages. Map by Mark Anderson Moore, courtesy North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh.

Gold ring found by archaeologists near Buxton on Hatteras Island in 2005, bearing markings that date to the late 1580s. Englishmen searching for the Lost Colony are known to have been in the region at that time. Courtesy of Professor David Phelps, East Carolina University.

1 January 2006 | Hairr, John