Eppes, Henry

By Steven A. Hill. Copyright 2017. Published with permission. For personal educational use and not for further distribution.

16 Sept 1830 - 29 Jan 1903

See also: Eppes, Charles Montgomery (son of Henry Eppes); Constitutional Convention, 1868: "Black Caucus".

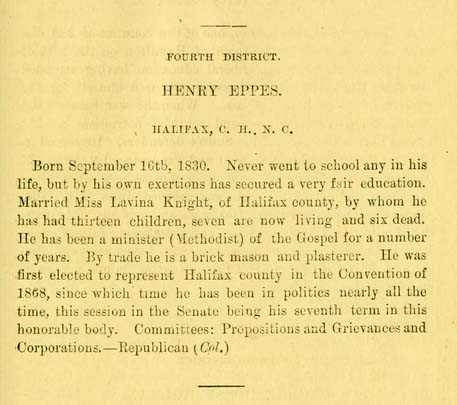

Henry Eppes, an African American politician and prominent A.M.E. Minister, was born enslaved in Halifax County on September 16, 1830, and died on or about January 29, 1903. He worked for the Freedmen’s Bureau immediately following the Civil War and also was described as having worked as a brick mason and plasterer. Henry Eppes’ political affiliation was as a Republican who represented Halifax County as a Senator in the state legislature. He was married to Lavina Knight of Halifax County, and they had thirteen children, including educational leader Charles Montgomery Eppes (1858–1942) of Greenville, North Carolina.

Henry Eppes, an African American politician and prominent A.M.E. Minister, was born enslaved in Halifax County on September 16, 1830, and died on or about January 29, 1903. He worked for the Freedmen’s Bureau immediately following the Civil War and also was described as having worked as a brick mason and plasterer. Henry Eppes’ political affiliation was as a Republican who represented Halifax County as a Senator in the state legislature. He was married to Lavina Knight of Halifax County, and they had thirteen children, including educational leader Charles Montgomery Eppes (1858–1942) of Greenville, North Carolina.

In a 2013 Senate Joint Resolution by the North Carolina General Assembly, Senator Henry Eppes was acknowledged as being one of the African American pioneers in the state’s political and racial history. The resolution stated that "from 1868 to 1900, no fewer than 111 African Americans were elected to the North Carolina General Assembly, but between 1900 through 1968, no African Americans were elected as a result of racial segregation enforced by "Jim Crow" laws and impediments to voting for African Americans such as the use of literacy tests and poll taxes." These "impediments" were the direct result of a state constitutional amendment drafted by the General Assembly in 1899 and approved in the election of 1900 that deliberately sought to exclude blacks from voting, by ensuring that only literate white males could vote.

One of a few African Americans who was politically active in both the Reconstruction (1865-1877) and post Reconstruction years (1877-1900), Henry Eppes secured a unique position in North Carolina’s legislative history. Chosen as a delegate to the state’s Freedmen’s Convention in 1866, he was first elected representative of Halifax County at the state’s 1868 constitutional convention. Reverend Henry Eppes served for seven terms as a State Senator of North Carolina. He served as a member of North Carolina’s State Senate from 1868 until 1887, with the exception of one session. Henry Eppes was a leader in the eastern part of the state, the “black belt,” of North Carolina, where the African American population sometimes outnumbered whites.

In 1866, he represented Halifax County at the “State Equal Rights League Convention of Freedmen.” A stated purpose of the meeting was to have blacks unite and communicate the challenges that they confronted so that the world would “know of the cruelties inflicted upon us, and the disadvantages under which we labor.” “Disadvantages” for former slaves enumerated included “killing, shooting, and robbing the unprotected people, for the most trivial offence, and, in many instances, for no offence at all . . .” Eppes’ home county, Halifax, earned special mention at the 1866 gathering for being a particular hotspot for criminal violence against former slaves.

He continued his service to North Carolina the next year when he was appointed by the “Headquarters of the Second Military District under General Orders No. 60” as an official “register” by the Union military government for Halifax County.” In 1869, Henry Eppes was also named Halifax County’s justice of the peace.

With the Civil War over, slavery abolished, and the Fourteenth Amendment carved into law, African Americans in North Carolina believed that a new era had only just begun whereby their rights of citizenship would be fully exercised in 1865. Henry Eppes and his fellow legislators were ebullient at the election of Lincoln’s former top general, Ulysses S. Grant, as President in 1868: "Our cause has triumphed . . .By his election our status is settled. We are men!” Eppes nominated Grant for a second term when he made the journey to Philadelphia, where the Republican national convention was held in 1872.

As a state senator, Henry Eppes’ activities and committee assignments were numerous: Committee on Privileges and Elections and on the Committee on Corporations; Committee for the selection of a new penitentiary location; Committee on Propositions and Grievances; Committee on Military Affairs; Committee on Agriculture; Special Committee on Roads.

During Eppes’ tenure in the Senate, the Ku Klux Klan had been active in both Carolinas as early as 1867-1868. By the middle of 1870, North Carolina had recorded over 200 documented KKK related actions in twenty counties; of these attacks, 174 of them involved blacks. Whites who had been attacked by the Klan during this period were northerners employed by the Freedmen's Bureau, teachers in black schools, or vocal white Republicans.

These intimidations prompted Henry Eppes to invoke the power of the state to ensure the preservation of blacks’ newfound rights as citizens. For example, he supported citizens’ equal rights when traveling on public conveyances. A more vigorous endorsement of state action by Henry Eppes came in 1870 when he supported the militia bill whose purpose was to stop the Ku Klux Klan’s ongoing violence toward blacks.

Henry Eppes was also an early advocate for the education of black students in North Carolina. In 1887, he proposed the creation of a statewide normal and collegiate institution which initially failed to become law, but a similar and more successful effort by another black Senator in 1891 passed and resulted in what would later become Elizabeth City State University.

Following his career in politics, Henry Eppes was involved in real estate speculation in both Wilmington and in Halifax, North Carolina. Home ownership for African Americans displayed an outward badge of economic freedom and strength, as well as a mark of citizenship. Wilmington provided opportunity for former slaves and their children to exercise their rights as citizens and create and keep wealth. The city possessed an active business culture where black owned businesses demonstrated sustained viability between the end of the Civil War and the late 1890s.

Henry Eppes saw opportunity in Wilmington in the 1880 and 1890s. Eppes was one of a group of African American leaders who had joined together in 1889 to form the People’s Perpetual Building and Loan Association. The group’s goal was to help empower shareholders to buy their own homes. Black leaders like Eppes saw the attainment of property as a step towards social and economic advancement for blacks. Created to help blacks own their own homes, the People’s Perpetual Building and Loan Association filled the void created by earlier institutions that had failed. From 1889 to 1898, the Association provided over seventy loans to shareholders.

Activity of the Association stopped in December 1898, soon after the November 10 Wilmington Coup. While most of the loans associated with the Association were cancelled or paid in full, Henry Eppes’ foray into real estate speculation left him deeply in debt by the year of his death in 1903. Henry Eppes was buried in Halifax.

[Note: Henry Eppes’ death has been mistakenly reported as being in 1917 in many known sources about him. Henry Eppes died around January 29, 1903. Charles Montgomery Eppes, his son, wrote in a letter to Charles N. Hunter dated February 6, 1903: “I am reminded of some very nice things you used to say about my father who was buried on Jan. 29 at Halifax.” Copious amounts of corroborating documents that confirm the 1903 death date can be found, including in estate proceedings regarding Reverend Henry Eppes’ death in New Hanover County in North Carolina Estate Files, 1663-1979. The mistaken reportage of Henry Eppes’ death could be attributed to the death certificate of one “Harry Epps” of Halifax County, North Carolina, who died in 1917.]

References:

Eric Foner, Freedom’s Lawmakers: A Directory of Black Officeholders during Reconstruction, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 1996), 7.

The Washington Post Feb 2, 1903, pg. 4.

J. S. Tomlinson, Tar heel sketch-book. A brief biographical sketch of the life and public acts of the members of the General assembly of North Carolina. Session of 1879, (Raleigh: Raleigh news steam book and job print) 9. https://archive.org/details/tarheelsketchboo00tomli

Thomas Yenser, ed., Who’s Who in Colored America, sixth edition (Thomas Yenser Publisher, 2317 NEWKIRK AVENUE BROOKLYN, NEW YORK. 1942) 176.

North Carolina Estate Files, 1663-1979. State Archives, Raleigh; FHL microfilm 2,385,58.

Elizabeth Balanoff, “Negro Legislators in the North Carolina General Assembly July, 1868-February, 1872,” North Carolina Historical Review, 49, No. 1 (January, 1972): 22-55.

General Assembly of North Carolina Session 2013. S D Senate Joint Resolution DRSJR15075-LG-55B (02/20).

The Western Democrat, (Charlotte), December 03, 1867. https://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn84020712/1867-12-03/ed-1/

NOTED COLORED MAN DEAD.: Rev. Henry Eppes Was Prominent as a Politician and Preacher,” Washington Post (Washington, D.C.), February 2, 1903.

Who’s Who in Colored America. 1942.

Eric Anderson, Race and Politics in North Carolina 1872-1901 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1981) 139

Minutes of the Freedmen's Convention, Held in the City of Raleigh, on the 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th of October, 1866: Electronic Edition. Freedmen's Convention (1866 : Raleigh, N.C.)

Western Democrat (Charlotte, N.C.), July 30, 1867.

Headquarters Second Military District, Order No. 60, Charleston, SC. July 19, 1867, "North Carolina, Freedmen's Bureau Assistant Commissioner Records, 1862-1870."

“Henry Eppes, for amount allowed Dudley and Major HanIon, for the arrest of a fugitive from justice,” Executive and Legislative documents laid before the General Assembly of North-Carolina [1869; 1870] CreatorNorth Carolina., Date 1869; 1870. https://digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/executive-and-legislative-doc...

LeRae Umfleet, 1898 Wilmington Race Riot Report (Raleigh: Office of Archives and History North Carolina, May 31, 2006).

Letter from Charles M. Eppes to Charles N. Hunter, February 6, 1903. Charles H. Hunter Papers, Duke University Rubenstein Library.

23 August 2017 | Hill, Steven