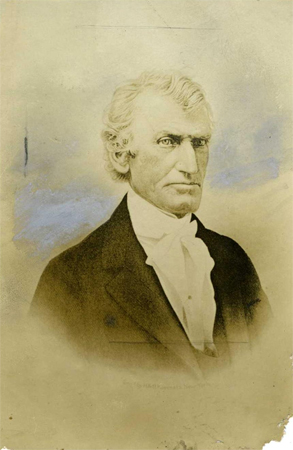

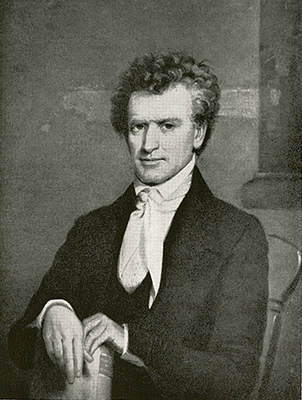

Ruffin, Thomas

17 Nov. 1787–15 Jan. 1870

Thomas Ruffin, chief justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court, statesman, and agriculturist, was born at Newington, the residence of his maternal grandfather, Thomas Roane, in King and Queen County, Va. His father was Sterling Ruffin, a substantial planter of Essex County who later moved to Rockingham County, N.C. His mother was Alice Roane, whose distinguished family included Spencer Roane, chief justice of the Virginia Supreme Court.

Thomas Ruffin, chief justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court, statesman, and agriculturist, was born at Newington, the residence of his maternal grandfather, Thomas Roane, in King and Queen County, Va. His father was Sterling Ruffin, a substantial planter of Essex County who later moved to Rockingham County, N.C. His mother was Alice Roane, whose distinguished family included Spencer Roane, chief justice of the Virginia Supreme Court.

Young Thomas attended local schools in Essex County and prepared for college at the classical academy of Marcus George in Warrenton, N.C. Among his schoolmates, who became lifelong friends, were Robert Brodnax of Rockingham County; Cadwallader Jones, then of Halifax but later of Orange; and Weldon N. Edwards of Warren. He entered the junior class of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton) and was graduated in 1805, after which he began the study of law under David Robertson, a learned Scottish lawyer of Petersburg, Va. There he was a classmate of Winfield Scott. In 1807 he followed his family to Rockingham County and completed his law studies under Archibald D. Murphey, with whom he would later be intimately connected. He was admitted to the bar in 1808 and began a practice in Hillsborough, where, on 9 Dec. 1809, he married Anne, the daughter of William Kirkland, whose handsome home, Ayr Mount, still stands east of the town.

At the Orange County bar and neighboring ones he joined a distinguished array of barristers, including Murphey, Frederick Nash, William Norwood, Duncan Cameron, Henry Seawell, and Leonard Henderson. An ardent Jeffersonian Democrat, he represented the borough of Hillsborough in the North Carolina House of Commons in 1813, 1815, and 1816. His only other purely political office was as a Crawford candidate for presidential elector in 1824.

In 1816 Ruffin was elected by the legislature as a superior court judge but resigned after two years to return to practice in order to repay a security debt contracted by Murphey. For forty-three weeks a year he almost always attended two courts a week, despite the weather and the fatiguing and hazardous traveling conditions. He served as reporter of the state supreme court in 1820 and 1821 (his reports are found in the first volume of Francis L. Hawks, North Carolina [Supreme Court] Reports ) and then returned again to his legal practice, in which by 1825, according to Justice Leonard Henderson, he stood at the head of his profession. In 1825 Ruffin again accepted the appointment as judge of the superior court, but in 1828 he again resigned, this time to become president of the State Bank of North Carolina, which had become deeply in debt. After a year he effectively redeemed the institution and prepared the way to close out the remaining term of its charter in credit.

While he was so engaged, the legislature, upon the death of Chief Justice Henderson, elected him associate justice of the supreme court in 1829. In 1833 he became chief justice, a position he held until 1852, when he resigned to retire to the Hermitage, his plantation in Alamance County, which he had acquired from Murphey in satisfaction of debts. Six years later, however, by almost unanimous election of the legislature, he was returned as chief justice but resigned after one year.

Ruffin was a North Carolina delegate at the Washington Peace Conference in February 1861 in the last-ditch effort to effect a compromise between North and South. As an ardent Unionist he sought diligently and eloquently to avert war and received the only ovation save one at the nineteen-day session. After the conference's failure and President Abraham Lincoln's call for volunteers from North Carolina, Ruffin still denied the constitutional right of secession but championed a revolutionary separation from the United States. He was elected to the Secession Convention in Raleigh, on 20 May 1861, where he supported the George Badger ordinance, which based secession on the right of revolution, rather than on the right of secession, sponsored by Burton Craige. Realizing the strong opposition to the former, Ruffin proposed a compromise solution that called for immediate secession but one that set forth the reasons. After further debate Ruffin finally acceded to Craige's motion, which was unanimously adopted. Henceforth he vigorously supported the Confederate cause, heart and soul—and pocketbook. He and William A. Graham, at the request of the convention, went to Richmond and arranged with the Confederate government for the reception of state troops and volunteers into the Confederate government.

After Appomattox, Ruffin renewed his allegiance to the United States and received an individual pardon from Andrew Johnson. Though he bitterly opposed congressional Reconstruction on constitutional grounds, he also opposed the Ku Klux Klan movement; he wrote his son that the Klan was a proceeding "against Law and the Civil power of Government" that was "wrong—all wrong."

Throughout his life, Ruffin was a leading agriculturist who operated two plantations—one in Rockingham County and the other at the Hermitage in Alamance. He and the "Southern Agriculturist," Edmund Ruffin of Virginia, his kinsman whose son married Ruffin's daughter, carried on an extensive correspondence about the latest developments in scientific agriculture. As a result of his influence in extending this knowledge, he was chosen president of the State Agricultural Society (1854–60).

A devoted member of the Episcopal church, Ruffin gave the land for St. Matthew's Church, Hillsborough, on the site where Anne Kirkland had accepted his proposal of matrimony. For many years he served on the vestry and was a delegate to the triennial General Convention of the Episcopal church.

He was also a loyal friend of The University of North Carolina. His advice was frequently sought by Presidents Joseph Caldwell and David L. Swain, and he served as a trustee from 1813 to 1831 and again from 1842 to 1868, when Reconstruction terminated the old board's existence. In 1834 the university awarded him a doctor of laws degree.

Ruffin's chief contribution to his adopted state and to the nation was as a jurist, whose reputation was recognized wherever English law was known. Authorities such as Chief Justice William Howard Taft and Justice Felix Frankfurter ranked him as a pioneer in adapting the English common law to the quasi-frontier conditions in the United States, as a result of which his decisions were followed more than any others by the southern and western courts. Roscoe Pound, long dean of the Harvard Law School, rated him one of the ten foremost jurists in the United States. Ruffin's 1,453 opinions, which embrace almost every topic of civil and criminal law and equity, are noted for their force of reasoning, breadth of view, clarity, and departure from precedent if Ruffin felt it would administer justice. In Hoke v. Henderson (15 N.C. 1), the first case of its kind in the United States, he held that the holder of a public office had an estate in it and therefore the legislature could not divest him of it because such a procedure was an exercise of judicial power. In Raleigh and Gaston Railroad Company v. Davis (19 N.C. 263), he ruled that the legislature had the power to provide for condemnation of a right of way for railroad purposes without the owner's being entitled to a jury trial for assessment of damages. Ruffin's judicial record included several important cases for the legal status of slavery and enslaved people in North Carolina. Perhaps his most sensational case was State v. Mann (13 N.C. 263), in which he handed down the stern decision that "the power of the master must be absolute to render the submission of the slave perfect" and that the enslaver or hirer of an enslaved person was not liable for a battery upon the enslaved person. Ruffin also ruled on the case State v. Negro Will, which was a 1834 North Carolina Supreme Court decision standing for the general proposition that if an enslaved person in self-defense, under circumstances strongly calculated to excite passions of terror and resentment, kills an enslaver, the homicide is not murder but manslaughter. Ruffin's decision on the case aligned with Justices Joseph J. Daniel and William Gaston.

After the war, Ruffin moved from the Hermitage to Hillsborough, where he died, survived by his wife and thirteen of his fourteen children. He was buried in St. Matthew's churchyard in the grounds that he had donated almost a half century before. His portrait by James Hart hangs in the law school library at The University of North Carolina.

References:

Samuel A. Ashe, ed., Biographical History of North Carolina, vol. 5 (1906).

DAB, vol. 8 (1935).

J. G. de Roulhac Hamilton, ed., The Papers of Thomas Ruffin, vols. 2–4 (1918–20).

Ruffin family Bible (possession of Mrs. Charlotte Trant Roulhac, Mount Vernon, N.Y.).

Thomas Ruffin Papers (Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill).

Additional Resources:

North Carolina Bar Association; Clark, Walter. Addresses at the unveiling and presentation to the state of the statue of Thomas Ruffin by the North Carolina Bar Association : delivered in the hall of the House of Representatives, 1 February, 1915. Raleigh, N.C.: Edwards & Broughton Print. Co. 1915. https://archive.org/details/addressesatunvei161nort (accessed January 2, 2014).

Greene, Sally. "Judge Thomas Ruffin, Presiding Over a Vanished Era," Commemorative Landscapes of North Carolina. https://docsouth.unc.edu/commland/features/essays/greene/ (accessed January 2, 2014).

Image Credits:

Unidentified artist, circa 1825. "Thomas Ruffin." North Carolina Portrait Index, 1700-1860. Chapel Hill: UNC Press. p. 203. (Digital page 217). https://www.worldcat.org/title/832326?oclcNum=832326. Accessed 10/15/2014.

"Photograph of a portrait of Chief Justice Thomas Ruffin by Daniel Harvey, Jr."1900-1920. Accession #: H.1946.14.128, North Carolina Museum of History. (accessed January 2, 2014).

1 January 1994 | Robinson, Blackwell P.