Johnston, James Cathcart

25 June 1782–9 May 1865

James Cathcart Johnston, planter, was born in Edenton, the sixth child and fourth son of Samuel (1733–1816) and Frances Cathcart (1751–1801) Johnston. His father, a lawyer, was governor of North Carolina from 1787 to 1789 and a U.S. senator from 1790 to 1793. His great-uncle, Gabriel Johnston (ca. 1698–1752), was North Carolina's royal governor from 1734 to 1752. James Iredell (1751–99), a lawyer, judge, and United States Supreme Court justice, was his uncle.

James Cathcart Johnston, planter, was born in Edenton, the sixth child and fourth son of Samuel (1733–1816) and Frances Cathcart (1751–1801) Johnston. His father, a lawyer, was governor of North Carolina from 1787 to 1789 and a U.S. senator from 1790 to 1793. His great-uncle, Gabriel Johnston (ca. 1698–1752), was North Carolina's royal governor from 1734 to 1752. James Iredell (1751–99), a lawyer, judge, and United States Supreme Court justice, was his uncle.

Johnston spent much of his childhood and youth away from home at various schools. At age eight, he was sent to school on Long Island, N.Y., while his family lived in New York City and his father served in Congress. From 1792 to 1796 he attended Woodbury School located in New Jersey near Philadelphia and studied under the Reverend Andrew Hunter. He then entered the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University) where he was a member of the American Whig Society. Johnston was graduated in 1799 and returned to North Carolina to live at Hermitage Plantation near Williamston with his parents, his sisters Penelope, Helen, and Frances, and his brother Gabriel. Accustomed to a busy schedule of classes and studies and to the camaraderie of schoolmates, he found life at the secluded plantation very quiet. To while away idle hours, he read books and became especially absorbed in metaphysics and history. He studied French at The University of North Carolina from July to November 1800 and on his return home began to read law under his father. Johnston immediately became apprehensive about a legal career and lamented to friends that his studies were "rather dry and intricate." Nevertheless, he persevered and received a license to practice on 11 Apr. 1804. But while he had been completing his legal training, his attention had turned to agriculture. He began to manage his father's plantation in Pasquotank County and slowly drifted away from the law. Hard work and personal management of his plantations over the next sixty years made Johnston one of the state's most innovative and prosperous planters.

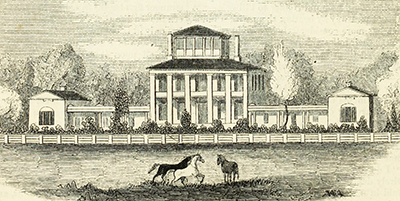

He lived at Hayes Plantation in Chowan County, located east of Edenton and bordered by Queen Anne's Creek and Edenton Bay. The farm had been purchased by Samuel Johnston in 1765 from David Rieusett, whose brother John had bought it from William and Harding Jones. Samuel gave the 665-acre plantation to his son in 1814 and instructed him to build a house on it, as the one there was uninhabitable. Johnston commissioned William Nichols, an English architect living in Edenton, to design the plantation house. Construction began in the fall of 1815, and Johnston and his sisters moved into it two years later. Nichols's plan featured a central section with two floors that was flanked by two single-story, curved wings with colonnades. The octagonal "Gothick" library at the end of one of the wings held Johnston's extensive collection of eighteenth-and nineteenth-century legal, political, and historical literature. The distinctive home was the focal point of the plantation that became famous throughout North Carolina. Over the years Johnston added to his Hayes property and by 1860 owned 1,374 acres of land.

The planter had extensive landholdings elsewhere in North Carolina. In Pasquotank County he owned several farms consisting of 2,740 acres. Poplar Plains, inherited from his father, was located along the Pasquotank River four miles below Elizabeth City. It adjoined his "Body" land and a plantation called Salem, which he purchased from Joseph Blount in 1819. Johnston's largest farm was Caledonia, located in Halifax County along the Roanoke River. Caledonia was also a bequest from his father, who had received it from his father-inlaw, William Cathcart. Johnston bought more land and increased the plantation's size from 2,375 to 7,834 acres. He also owned some land in Northampton County.

Johnston spent much of his time traveling from plantation to plantation to personally oversee their operations. His largest crop was corn; in addition, he grew wheat, oats, cotton, flax, potatoes, peas, and beans. He raised cattle, hogs, and sheep. The plantation products to be sold at markets were floated down river on Johnston's boats to storage firms at Plymouth, Elizabeth City, or Edenton; then they were shipped, often by his schooners and canal boats, to Savannah, Charleston, Norfolk, Baltimore, and New York. Commission merchants in these cities handled Johnston's profits, buying supplies for the plantations or investing the money in bank stocks and treasury notes for him.

Johnston spent much of his time traveling from plantation to plantation to personally oversee their operations. His largest crop was corn; in addition, he grew wheat, oats, cotton, flax, potatoes, peas, and beans. He raised cattle, hogs, and sheep. The plantation products to be sold at markets were floated down river on Johnston's boats to storage firms at Plymouth, Elizabeth City, or Edenton; then they were shipped, often by his schooners and canal boats, to Savannah, Charleston, Norfolk, Baltimore, and New York. Commission merchants in these cities handled Johnston's profits, buying supplies for the plantations or investing the money in bank stocks and treasury notes for him.

Keenly interested in modern developments in agriculture, Johnston continually experimented with new farming techniques to improve his plantations. He cleared unused land, dug irrigation canals, and enriched his soil with fertilizers. He also invested in new agricultural machinery. Early in his career he built a windmill at Hayes but later dismantled it. He then constructed steam-powered saw, grist, and flour mills, which produced lumber, flour, and cornmeal for both plantation and market. In addition, he bought cotton gins and threshing machines. Johnston's innovations enabled him gradually to increase his agricultural production as well as the value and quality of his properties. Whereas in 1829 he described his plantations as "large and extensive but ragged and tattered in some places bare to the skin and almost to the bone," he proudly wrote in 1846 that they were "in better order" than he had ever had them.

Johnston displayed a moderate attitude towards slavery. He treated his slaves respectably and expected the same in return so that his plantations would operate smoothly. In 1860 he owned a total of 555 slaves—103 at Hayes, 181 at his Pasquotank County farms, and 271 at Caledonia. He was attentive to his slaves' needs and capabilities. They made their own clothes, and he regularly provided them with shoes, hats, blankets, medical care, and food. They were allowed to raise and to sell crops from their gardens. He trained several as overseers and frequently left the slaves at his Pasquotank plantations alone with little or no white supervision. He punished them when he considered such action necessary, yet expressed compassion for them in the problem of slave revolts. Johnston felt that insurrections were most dangerous for blacks, viewed with suspicion by nervous whites, and thought that during periods of unrest it was best "to be at home to protect the poor creatures who have no law to protect them and have nothing to work up to but the presence and protection of their master." Freedom for slaves was not beyond his consideration. Several facts point to this interpretation: in 1841 he anonymously donated $250 to the American Colonization Society; in the 1850s he loaned $1,000 to a freed and widowed black and her five children for their resettlement in Ohio; and during the Civil War, he wrote that he preferred to give a pass to his slaves who wanted to go to freedom behind the Federal lines rather than to have them run away and make him appear to be a hard master, and themselves to be rascals.

During his leisure hours Johnston traveled a great deal, claiming that it served as a "substitute for the pleasure of domestic life." He seems to have fallen in love only once with a Miss Jones, whom he met on a trip to Sweet Springs, Va., in the summer of 1821. She, however, flatly refused his proposal of marriage the following year. Johnston also enjoyed the change of scenery and company that travel afforded, and he frequently journed northward to New York City and Saratoga Springs to visit friends. In 1845 he leased a cabin at White Sulphur Springs in Greenbriar, Va., thereafter becoming a regular summer and fall visitor to this and other fashionable mountain resorts in Virginia. In 1859 he bought a farm at Cedar Creek in Bath County, Va., built a house and log cabins, and began planting crops. The Civil War, however, ended this plan for a private mountain retreat.

During his leisure hours Johnston traveled a great deal, claiming that it served as a "substitute for the pleasure of domestic life." He seems to have fallen in love only once with a Miss Jones, whom he met on a trip to Sweet Springs, Va., in the summer of 1821. She, however, flatly refused his proposal of marriage the following year. Johnston also enjoyed the change of scenery and company that travel afforded, and he frequently journed northward to New York City and Saratoga Springs to visit friends. In 1845 he leased a cabin at White Sulphur Springs in Greenbriar, Va., thereafter becoming a regular summer and fall visitor to this and other fashionable mountain resorts in Virginia. In 1859 he bought a farm at Cedar Creek in Bath County, Va., built a house and log cabins, and began planting crops. The Civil War, however, ended this plan for a private mountain retreat.

Johnston preferred a private life, shunning public duties—he wrote that he disliked "public applause." He held few public offices, serving only on the North Carolina Board of Internal Improvements (1820–21) and on the board of trustees of The University of North Carolina (1818–63). He was very interested in public events, especially politics. He greatly respected many Federalists, including Washington, Marshall, Jay, and Hamilton. He supported the Whig party and particularly admired Daniel Webster and Henry Clay, although he eventually became disillusioned with the Whigs. Johnston was deeply disturbed as the Union was propelled towards civil war in 1860–61. He thought that the United States Constitution was of superior quality but that it had been improperly administered under President Buchanan. The South, in his opinion, had degenerated into a state of anarchy. He also believed that the doctrine of the "wicked" Secessionists would set a harmful precedent: "when a state government brakes [sic ] a most solemn contract with so little ceremony individuals will think it no sin to absolve themselves from any contract they may make and we may expect soon a general repudiation both of individuals as well as governments."

Johnston preferred a private life, shunning public duties—he wrote that he disliked "public applause." He held few public offices, serving only on the North Carolina Board of Internal Improvements (1820–21) and on the board of trustees of The University of North Carolina (1818–63). He was very interested in public events, especially politics. He greatly respected many Federalists, including Washington, Marshall, Jay, and Hamilton. He supported the Whig party and particularly admired Daniel Webster and Henry Clay, although he eventually became disillusioned with the Whigs. Johnston was deeply disturbed as the Union was propelled towards civil war in 1860–61. He thought that the United States Constitution was of superior quality but that it had been improperly administered under President Buchanan. The South, in his opinion, had degenerated into a state of anarchy. He also believed that the doctrine of the "wicked" Secessionists would set a harmful precedent: "when a state government brakes [sic ] a most solemn contract with so little ceremony individuals will think it no sin to absolve themselves from any contract they may make and we may expect soon a general repudiation both of individuals as well as governments."

Johnston never married. However, he fathered four daughters with Edith "Edy" Wood, who was an enslaved-then-manumitted woman. At one time, Johnston's friend, Capt. James Wood, was Edy's enslaver. Johnston manumitted Edy and their children in 1832; at that time, Edy was living in Baltimore with her enslaver, John Trimble. In 1836, two children died at ages eight and nine. His eldest daughter, Mary Virginia Wood Forten, died in Philadelphia of tuberculosis in 1840. Johnston's and Edy's youngest daughter was named Annie Wood (1831–1879).

At his death Johnston willed his real and personal property to three friends and made them co-executors of his estate. Edward Wood, an Edenton businessman, received his Chowan County property, including Hayes Plantation. Christopher W. Hollowell, a resident of Pasquotank County who had helped manage Johnston's farms in that county, was given Poplar Plains and the other Pasquotank properties. Caledonia's manager, Henry J. Futrell, inherited the property in Halifax and Northampton counties. Johnston's closest living relatives were cousins, and he did not leave them any of his land for several reasons. He had frequently given them money during his lifetime, and he thought that they had been inconsiderate of him by leaving him alone and unprotected at Hayes during the Civil War. He also considered them incapable of maintaining his properties. After spending his entire life building and improving his plantations, he did not wish them to be destroyed by poor management or divided up among his numerous relatives. He believed his three heirs to be honest, industrious men. Furthermore, Hollowell and Futrell had been faithful to him and protected his property, and Wood was a capable businessman who would keep his beloved Hayes intact and operate it as a productive farm. Johnston's cousins challenged the legitimacy of his will and its accompanying letters of instruction to the executors by which some of them were to receive monetary gifts; they claimed that Johnston had been mentally unstable when he had written the will and the letters. The will was finally established as legal in 1867, but, because additional suits were brought against its executors, Johnston's estate was not settled until 1871.

Johnston was an Episcopalian. He was buried at Hayes Plantation.

References:

Hayes Collection, Pettigrew Papers (Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina Library, Chapel Hill).

Calder Loth and Julius Trousdale Sadler, Jr., The Only Proper Style: Gothic Architecture in America (1975).

Mary Maillard. “‘Faithfully Drawn from Real Life’: Autobiographical Elements in Frank J. Webb’s The Garies and Their Friends.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 137, no. 3 (2013): 261–300. https://doi.org/10.5215/pennmaghistbio.137.3.0261.

C. Ford Peatross and Robert O. Mellown, William Nichols, Architect (1979).

Additional Resources:

"100 dollars reward." North Carolina Minerva and Raleigh Advertiser. September 9, 1814. http://dlas.uncg.edu/notices/notice/1402/

"James Cathcart Johnston." Findagrave.com. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/74815517/james-cathcart-johnston (accessed February 20, 2023).

"James C. Johnston (Chowan County)." Under Both Flags: Civil War in the Albemarle. Museum of the Albemarle. 2011. http://underbothflags.ncdcr.gov/divided-allegiances-characters/james-c-johnston.html (accessed May 13, 2014).

"Eady Woods." Legacy of Slavery in Maryland: An Archives of Maryland Electronic Publication. Annapolis, M.D.: Maryland State Archives. http://slavery2.msa.maryland.gov/pages/Search.aspx

Lemmon, Sarah McCulloh. The Pettigrew papers. Raleigh [N.C.] : State Dept. of Archives and History. 1971. https://archive.org/details/pettigrewpapers1988lemm (accessed August 15, 2013).

Image Credits:

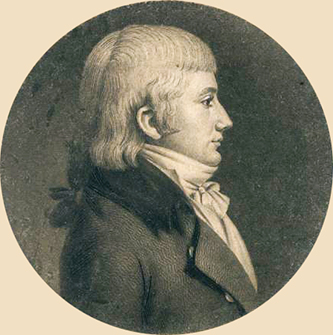

de Saint-Mémin, Charles Balthazar Julien Févret."James Cathcart Johnston." 1801. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. http://collections.si.edu/search/results.htm?q=record_ID:npg_S_NPG.74.39.5.7

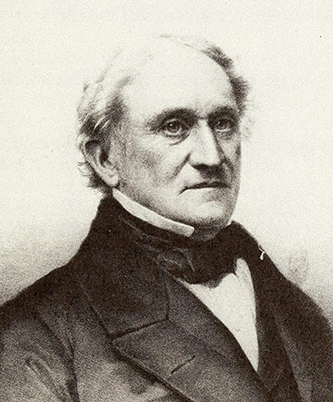

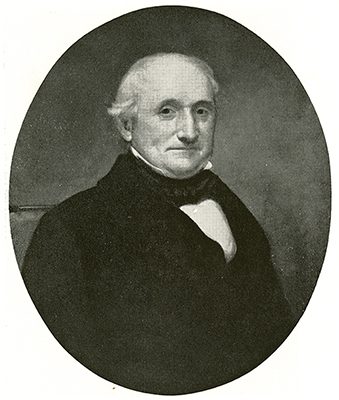

"James Cathcart Johnson of Hayes Plantation, Edenton, was a close friend of Ebenezer Pettigrew, and the two exchanged lengthy letters. Photograph of a lithograph from the files of the Division of Archives and History." The Pettigrew papers. Raleigh [N.C.] : State Dept. of Archives and History. 1971. 370.

" https://archive.org/stream/pettigrewpapers1988lemm#page/n425/mode/2up (accessed August 15, 2013).

"Seat of James C. Johnston, Esq.," Harper's New Monthly Magazine 14, no. 82 (March 1857). 448. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/stream/harpersnew14harper#page/448/mode/2up (accessed August 15, 2013).

Unidentified artist. "James Cathcart Johnston." North Carolina Portrait Index, 1700-1860. Chapel Hill: UNC Press. p. 126. (Digital page 140). https://www.worldcat.org/title/832326?oclcNum=832326. Accessed 10/15/2014.

1 January 1988 | Smith, Martha M.