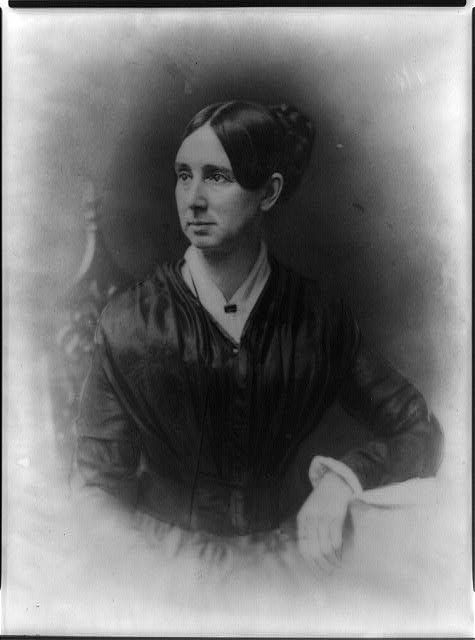

Dorothea Dix

by David L. Smiley

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian, Fall 1996; Revised by SLNC Government and Heritage Library, June 2023

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

Dorothea Lynde Dix is one example of a woman who made up her mind to do something and fought all odds to do it. Born in present-day Maine (which was part of Massachusetts until 1820) in 1802, Dix was a schoolteacher at the age of fourteen. She also was an author of children’s hymns and moral tales. Not until March 1841 did Dix begin her now-famous campaign against the mistreatment of the “insane” in America.

Dorothea Lynde Dix is one example of a woman who made up her mind to do something and fought all odds to do it. Born in present-day Maine (which was part of Massachusetts until 1820) in 1802, Dix was a schoolteacher at the age of fourteen. She also was an author of children’s hymns and moral tales. Not until March 1841 did Dix begin her now-famous campaign against the mistreatment of the “insane” in America.

Fighting Society and the Government

Society then believed that those with mental illnesses were possessed by demons and had to be imprisoned. Prison keepers believed these persons felt no cold and disliked being clean. In March 1841 Dix was visiting a jail near Boston to teach a Sunday school class. She became dismayed at the sight of sick people who had committed no crimes being kept in a room without comforts or cleanliness. She found “Insane persons confined . . . in cages, closets, cellars, stalls, pens! Chained, naked, beaten with rods, and lashed into obedience!” Dix resolved to do something to help them.

Her fight was not easy. At that time, women were not allowed to vote. In fact, it was considered improper for a woman even to speak in public forums or to explore any kind of interest outside her home and household duties. Those attitudes did not stop Dix.

She reported her findings to the Massachusetts state legislature in 1843. Dix displayed masterful tact and understanding as she began her efforts to make a change. Working through cooperative and influential men, she petitioned the legislatures of state after state for funds and officials to care for the insane. In each state her method was the same: a careful study of actual conditions, a document that factually described these conditions, and an appeal for public assistance to the unfortunates. By 1845 she had helped to expand three psychiatric hospitals and to start three others.

A Different Approach for North Carolina

Dix was weak and often ill, conditions that were not improved during her frequent travels by carriage and coach. In her notes, as she came to North Carolina from Tennessee in 1848, she reported that she “encountered nothing so dangerous as the river fords,” stream crossings where no bridges had been built or ferries installed. Upon her arrival in Raleigh, she tried a different method to gain support. In doing so, she presented one of the most magnificent statements in American social and legislative history, her Memorial Soliciting a State Hospital for the Protection and Cure of the Insane.

Dix declared that people with mental illnesses were unable to speak for themselves. She asked the General Assembly to look through her to see the “poor, crazed beings who pine in the cells, and stalls, and cages, and waste rooms of your poor-houses.” She continued by relating stories about different faces of madness—random acts of violence, domestic murders, and abuse—that she had seen as she journeyed across the state. She still maintained that patients needed humane care. But in this proposal she focused more on alerting the public about some of the dangers in allowing patients with mental illnesses to live among the general population without treatment. She then recommended institutional care as soon as possible to treat patients and return them to society.

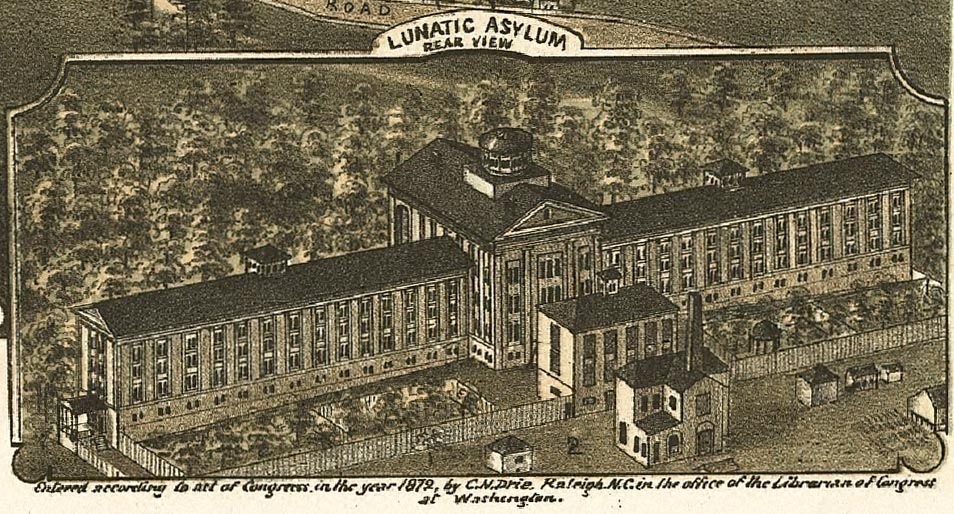

Dix petitioned for the construction of a state hospital in North Carolina. The hospital was to be on a site of at least one hundred acres and was to have ready supplies of water, wood and coal, abundant sunlight, and modern kitchens and laundries. Unfortunately, the price rose to $100,000—half of the state’s budget. Few legislators backed the expensive project, and it failed to be funded.

A Surprising Assist

A Surprising Assist

An unexpected event enabled Dix to succeed in her Tar Heel mission. Louisa Dobbin, wife of state legislator James C. Dobbin, lay dying in the same hotel where Dix was staying. Dix spent hours with Mrs. Dobbin, talking with her and reading the Bible. Late one night, Mrs. Dobbin murmured, “I fear I am sinking rapidly.” She thanked Dix for her compassion and help and asked if she could return the favor. “Tell your husband to sponsor my hospital bill,” Dix replied.

So it happened. When Dobbin returned to the legislature after his wife’s funeral, he spoke in support of the hospital. His speech, eloquent and emotional, is still remembered as one of North Carolina’s legendary orations. When the vote was taken, the bill was overwhelmingly approved.

David L. Smiley was a member of the history faculty at Wake Forest University from 1950 to 1991.

Resources:

Canadian Mental Health Association (2011). "History of Mental Illness Treatment." http://www.cmha.ca/bins/content_page.asp?cid=284-683-1480-1497-1622

McKown, Harry (2006). "January 1849 — Dorothea Dix Hospital," This Month in North Carolina History. University Libraries, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. http://www.learnnc.org/lp/editions/nchist-newnation/4780

National Institute of Health (2011). "The Science of Mental Illness," NIH Curriculum Supplement for Middle School.

National Institute of Mental Health (2010). "The Brain’s Inner Workings: Activities for Grades 9 through 12." http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/educational-resources/brains-inner-workings/the-brains-inner-workings-activities-for-grades-9-through-12.shtml

North Carolina Digital Collections search on "Dorothea Dix."

North Carolina Division of State Operated Healthcare Facilities (2010). "Dorothea Dix Hospital History." North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. http://www.ncdhhs.gov/dsohf/services/dix/history.htm

NCLive search on "Dorothea Dix."

Reddi, Vasantha. (2005). "Dorothea Lynde Dix (1802 -- 1887)." The Center for Nursing Advocacy. http://www.nursingadvocacy.org/press/pioneers/dix.html

WorldCat search on "Dorothea Dix" (Searches numerous library catalogs).

Image Credits:

"Dorothea Lynde Dix." Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-9797, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004671913/

Inset illustration in C. Drie, "Bird's eye view of the city of Raleigh, North Carolina 1872." Digital ID: g3904r pm006660, Library of Congress Geography and Map Division Washington, D.C. 20540-4650 USA. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g3904r.pm006660

1 January 1996 | Smiley, David L.