American Indians

Part i: Introduction; Part ii: American Indians before European contact; Part iii: Indian tribes from European contact to the era of removal; Part iv: The struggle for Indian sovereignty and cultural identity; Part v: North Carolina Indians today; Part vi: References; Cherokee Indians - Part 5: Trail of Tears and the creation of the Eastern Band of Cherokees

Part III: Indian tribes from European contact to the era of removal

Whether speaking in a historical context or of the present day, there are many ways to define an American Indian tribe. In its most widely understood form, however, an American Indian tribe is a group of bands, often (though not always) related by family ties, sharing common territories and having a feeling of unity deriving from similarities in culture, frequent friendly contacts, and other shared interests. More or less elaborate types of formal tribal organization may be defined within these basic outlines, but tribal groups can exist and function without them. One important way scholars have defined tribes for the purpose of study is by linguistic group. Many North Carolina tribes were displaced, emigrated to new places, or merged with other groups before their languages were recorded. However, word lists, town and tribal names, and other indicators suggest that by the sixteenth century, when European explorers first arrived in the region, native tribes populating North Carolina, both Mississippian and Woodland, comprised three linguistic groups: Iroquoian, Siouan, and Algonquian. The two most prominent Iroquoian tribes were the Cherokee, occupying the Blue Ridge Mountains and regions west and south, and the Tuscarora, occupying the Coastal Plain between Ocracoke Island and Topsail Island inland to the central Piedmont. The Neusioc and Coree, also Iroquoian, occupied the Cape Lookout environs of modern Carteret and Craven Counties.

Whether speaking in a historical context or of the present day, there are many ways to define an American Indian tribe. In its most widely understood form, however, an American Indian tribe is a group of bands, often (though not always) related by family ties, sharing common territories and having a feeling of unity deriving from similarities in culture, frequent friendly contacts, and other shared interests. More or less elaborate types of formal tribal organization may be defined within these basic outlines, but tribal groups can exist and function without them. One important way scholars have defined tribes for the purpose of study is by linguistic group. Many North Carolina tribes were displaced, emigrated to new places, or merged with other groups before their languages were recorded. However, word lists, town and tribal names, and other indicators suggest that by the sixteenth century, when European explorers first arrived in the region, native tribes populating North Carolina, both Mississippian and Woodland, comprised three linguistic groups: Iroquoian, Siouan, and Algonquian. The two most prominent Iroquoian tribes were the Cherokee, occupying the Blue Ridge Mountains and regions west and south, and the Tuscarora, occupying the Coastal Plain between Ocracoke Island and Topsail Island inland to the central Piedmont. The Neusioc and Coree, also Iroquoian, occupied the Cape Lookout environs of modern Carteret and Craven Counties.

Tribes of the Siouan linguistic group flourished throughout the central Piedmont, the Pee Dee River Valley, and the Lower Cape Fear region. These tribes included the Cape Fear, Catawba, Keyauwee, Occaneechi, Pee Dee (or Pedee), Saponi, Sissipahaw, Saura (Cheraw), Tutelo, Waxhaw, and Waccamaw peoples. Algonquian tribes settled and hunted the northeastern region of the state, including the Outer Banks north of Ocracoke and the Albemarle and Pamlico Sounds inland to the approximate western limit of the Coastal Plain. Representative tribes of the Algonquian group include the Chowanoac, Hatteras, Moratuc, Croatan, Secotan, Pamlico, Roanoke, and Weapemeoc (Yeopim).

Early European explorers and settlers to the land that would become North Carolina documented some of their encounters with the native peoples, providing firsthand descriptions of their appearance and demeanor. In July 1524 Giovanni da Verrazano, a Florentine navigator, became the first European to report on the characteristics of the Coastal Plain peoples. He described the natives he encountered on Bogue Banks and at the mouth of the Cape Fear River as ‘‘of a russet color,’’ tall, strong, and sporting long black hair worn ‘‘like a little tail.’’ The Indians were at first uneasy but soon became friendly toward the visitors.

The 1584 expedition sent by Sir Walter Raleigh and led by Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe was the first group of Englishmen to encounter natives on the Carolina coast. Arriving on Hatteras Island, the explorers were met by a friendly and curious people, with whom they exchanged gifts. The following year, a colony led by Ralph Lane was temporarily established in the region. Through the work of two of its members —scientist Thomas Harriot and artist John White—much information and documentation was gathered about the indigenous people. Reflecting the attitude of virtually all Englishmen of the era, Harriot described a people who were ‘‘very ingenious’’ and yet clearly inferior and in need of being brought ‘‘to civilities.’’ More than a century later, John Lawson, in A New Voyage to Carolina (1709), wrote at great length about the characteristics and customs of the Indians. Lawson’s attitude toward them remained similar to Harriot’s, stressing the need to treat the Indians well in order to encourage them to adopt the ‘‘worthier’’ customs of the English people.

The European discovery and settlement of the Carolina region signaled an era of radical change for local Indians, one marked by the toppling of the previous Indian way of life and a tragic and unrelenting decline in their population. The various strains of European diseases such as smallpox, bubonic plague, typhus, and measles inflicted severe misery upon many Indian tribes, which had no immunity against them. A massive smallpox epidemic in 1695 among the Pamlico Indians, and a similarly devastating outbreak that wiped out nearly half of the Cherokee in 1738, are but two examples of the deadly effects these diseases had on the Indian population.

At the same time that European settlement brought violent conflict between whites and Indians, it also increased the occurrence of warfare between Indian tribes. There were several factors influencing these hostilities. Many historians have concluded that a central cause of the problem was trade between the natives and the newcomers. Initially, there is evidence to suggest that North Carolina’s native peoples worked and lived cooperatively with the Europeans, teaching them agricultural techniques for corn, tobacco, and other cultivation as well as fishing and other necessary survival skills. In return, the white settlers offered the Indians manufactured goods from their homeland. But this trade led to a massive upheaval in both the ways Indians related to each other and how they came to view the white settlers. The introduction of these items resulted in the Indians’ becoming increasingly reliant on products such as metal knives, hoes, and hatchets as well as guns and ammunition. The acceptance of these effective new tools and other trade products made them vulnerable to manipulation by white traders and colonial authorities, who often turned one native tribe against another for political, economic, or other purposes. Many unscrupulous white traders also charged unfairly high prices for their wares, giving rise to ill feelings among natives that often led to conflict.

Furthermore, providing the Europeans with commodities they demanded—not only material products like deerskins but also human products like the labor enslaved American Indian people—caused tremendous competition among American Indian tribes and often resulted in violence between them. The pressure exerted on the American Indian population by the constant expansion of European colonization also caused many hostile acts on both parts. The Tuscarora War of 1711–13 represented an early pinnacle of American Indian resistance against European encroachment. At the outbreak of this conflict, the Tuscarora were the most powerful tribe in the eastern portion of North Carolina, with alliances that stretched both northward and southward into what are now Virginia and South Carolina. Due to German and Swiss colonists settling New Bern on the Neuse River in Tuscarora lands -- combined with settler's dishonorable trade deals with the Tuscarora and enslavement of Tuscarora families -- the Tuscarora attacked the English. Led by Chief Hancock, the Tuscarora attacked the town and nearby settlements in September 1711. The Tuscarora warriors killed 120 colonists and captured others, destroyed houses and barns, and confiscated crops and livestock. For the next year and a half, many individual battles occurred, sparked by both sides, until the Tuscarora were finally defeated at the village of Neoheroka in March 1713. Debilitated after the Tuscarora War, the weakened tribes of Eastern NC could no longer use war to combat English colonialism. The tribes and members of the Tuscarora that had fought against the English colonists were pushed from NC to New York and Canada to join the Iroquois Confederacy. The tribes and Tuscarora that sided with the English, however, remained behind on reservations of land in Bertie County that were prescribed to them by colonial and royal courts. Tuscarora diplomats and dignitaries appealed to English colonial courts to solve matters regarding their reservations through the colonial legal system. In doing so, they hoped to maintain their tribal identities despite being less numerous and resourced due to the loss in the war. Diplomatic transactions were also often complicated by the differences in understanding political hierarchy, which varied between the tribes and the English. While certain territorial boundaries were upheld in English courts by judicial officials, English settlers ignored the prescribed boundaries and pushed the tribes almost completely off of their reservations before the American Revolution began.

The defeat and subsequent relocation of the Tuscarora resulted in even greater westward expansion of white settlements during the eighteenth century. This expansion led to increased conflict with the inland tribes, particularly the Cherokee, with more than 40 towns and six times as many people as the Tuscarora, occupying the mountainous lands of southwestern North Carolina as well as parts of what are now eastern Tennessee, South Carolina, northern Georgia, and northeastern Alabama. During the French and Indian War (1754–63) the Cherokee sided with the French, and they later sided with the British in the American Revolution as a result of a royal proclamation that prohibited colonial settlement in the lands west of the Appalachian Mountains. Many colonists consequently considered the Cherokee hostile, and assaults on Cherokee towns became exceedingly brutal. Cherokee fields and storehouses were often destroyed, and many Cherokees were left to starve.

Through the latter part of the eighteenth century, the Cherokee and the other native people of the Carolinas were compelled by force or by treaty to cede much of their land to white settlers. Adjusting to these extreme circumstances, many Indians adopted aspects of Western culture, creating schools, churches, businesses, and forms of governance that would be recognized by non-Indians. Most famous among these efforts was the development of a written language, or syllabary, by the Cherokee Sequoyah. Despite these changes and the positive impression they might have had on whites, Indian land remained a target of white desire, and the concept of removing Indians to western lands continued to gain support. In 1830 Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, which opened the way for North Carolina and other states to force the Cherokee and their neighbors to relocate. Removal of the Cherokee people to present-day Oklahoma began in May 1838, and approximately 4,000 Cherokee people died on the infamous Trail of Tears to their new home. Nevertheless, some Indian people remained in North Carolina, maintaining a distinct cultural identity and autonomy in the face of enormous challenges. The largest of these remaining groups, known as the Oconaluftee Cherokee, claimed North Carolina citizenship rather than membership in the Cherokee Nation, and therefore avoided removal. The Oconaluftee Cherokee eventually constituted what became the modern Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.

Keep reading > Part IV: The struggle for Indian sovereignty and cultural identity ![]()

References:

LeMaster, Michelle. “In the ‘Scolding Houses’: Indians and the Law in Eastern North Carolina, 1684-1760.” The North Carolina Historical Review 83, no. 2 (2006): 193–232. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23523091.

Image credits:

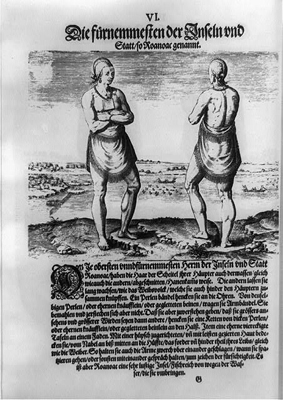

Bry, Theodor de. 1600. "A chief of Roanoke." Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Online at http://loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3b36279. Accessed 11/2011.

1 January 2006 | DiNome, William G.