Prisoners of War in North Carolina

"Enemies and Friends"

by Dr. Robert D. Billinger Jr.

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian. Spring 2008.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

Related Entry: WWII

They were not from the Tar Heel State. They spoke foreign languages and wore different uniforms from those of the American military. They had names that sounded strange to Tar Heel ears. They were among the thousands of prisoners of war (POWs) who spent time in North Carolina during World War II. Farm kids sometimes saw foreign prisoners helping with their fathers’ peanut harvests, picking cotton on a neighboring farm, or cutting pulpwood in the woods nearby. Attending a baseball game in Charlotte or sitting in a restaurant or movie theater in Monroe, North Carolinians might encounter Italian-speaking members of Italian Service Units—former POWs who had taken an oath of alliance to the new anti-German government in Italy and gotten American uniforms and day passes to see the local sights.

They were not from the Tar Heel State. They spoke foreign languages and wore different uniforms from those of the American military. They had names that sounded strange to Tar Heel ears. They were among the thousands of prisoners of war (POWs) who spent time in North Carolina during World War II. Farm kids sometimes saw foreign prisoners helping with their fathers’ peanut harvests, picking cotton on a neighboring farm, or cutting pulpwood in the woods nearby. Attending a baseball game in Charlotte or sitting in a restaurant or movie theater in Monroe, North Carolinians might encounter Italian-speaking members of Italian Service Units—former POWs who had taken an oath of alliance to the new anti-German government in Italy and gotten American uniforms and day passes to see the local sights.

Each had his own interesting story. For example, Heinrich Bollmann—a POW at the camp at Fort Bragg—was rescued from the U-352 sunk by the U.S. Coast Guard off the North Carolina coast in May 1942. Giuseppe Pagliarulo—a soldier of Benito Mussolini’s army captured in Tunisia, Africa, in May 1943—later trained as a member of an Italian Service Unit at Camp Sutton in Monroe. Matthias Buschheuer—a POW at Camp Sutton—was a veteran of Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps, also captured in Tunisia, Africa, in May 1943. Fritz Teichmann was a member of the German Luftwaffe (air corps), captured in Sicily, Italy, in July 1943, and held as a POW at Camp Butner. Max Reiter, a fellow prisoner at Camp Butner, had been a member of the Waffen-SS (the German Nazi Party’s own armed military unit) and was wounded and captured in Normandy, France, in June 1944.

They all came to North Carolina as enemies of the United States, but many later left as long-term friends of Americans and one another. Because of the relative secrecy of the army’s POW program, few people—other than the guards who ran the camps and the civilian employers who “leased” the services of POWs from the military—even knew about the POWs in the Tar Heel State. Today many people still are not aware that there were thousands of war prisoners held here.

Some of the first prisoners to arrive in the United States were Italians. By the end of 1943, nearly 50,000 Italian POWs were held in 27 camps in 23 states, including North Carolina. Camp Butner was one of the major barbed-wire-encircled camps, with about 3,000 Italian POWs. After the collapse of Mussolini’s regime in September 1943, the new Italian government had allied itself with the United States. The next March, the American army created Italian Service Units (ISUs) of approximately 30,000 Italian POWs who were willing to take an oath of allegiance to the new Italian government and serve as noncombatant auxiliaries to American forces. About 3,500 of these ISU men came to Camp Sutton in Monroe in spring 1944 for special training at the army engineer facility. Other than Pine Camp in New York State, Camp Sutton held the largest number of ISU men at that time. While at Camp Sutton, the men received American training and uniforms. They were allowed to leave the base, and one can imagine how their presence aroused local people’s interest.

The Italian Service Units in the Monroe area attracted positive attention from the press and the public in ways that the German POW presence throughout the state did not. The Germans, as POWs, were not allowed outside American military camps unless closely supervised on work details approved by the military.

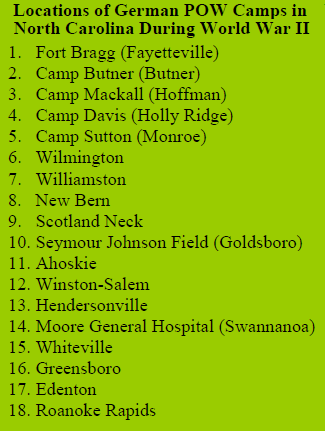

At the end of the war in Europe, in May 1945, there were 378,000 German prisoners of war held in 155 base camps and 511 branch camps in forty-six of the forty-eight states. North Carolina had 2 major POW base camps: specially barbed-wire-enclosed camps within the larger American military bases at Camp Butner and at Fort Bragg. Each of these held between 2,000 and 3,000 German POWs. There were also 16 smaller branch camps across the state, each with 250 to 350 Germans, so that North Carolina held a total of some 10,000 “Nazi” soldiers, as the wartime American press described them.

At the end of the war in Europe, in May 1945, there were 378,000 German prisoners of war held in 155 base camps and 511 branch camps in forty-six of the forty-eight states. North Carolina had 2 major POW base camps: specially barbed-wire-enclosed camps within the larger American military bases at Camp Butner and at Fort Bragg. Each of these held between 2,000 and 3,000 German POWs. There were also 16 smaller branch camps across the state, each with 250 to 350 Germans, so that North Carolina held a total of some 10,000 “Nazi” soldiers, as the wartime American press described them.

For all of them to be “Nazis,” they would have had to be loyal supporters of Adolf Hitler’s National Socialist German Workers Party. In fact, not all the “Germans” were even Germans, let alone “Nazis.” Camp Butner’s “nationalities” compound at one point held 332 Czechs, 150 Poles, 147 Dutchmen, 117 Frenchmen, 34 Austrians, 11 Luxembourgers, and 1 Lithuanian—men captured wearing German uniforms but forced to fight by German oppressors. (Earlier there had been Russians and even Mongolians.) While Hitler did attract many non-German volunteers to his armies, some “volunteers” had been coerced. Once captured, a number of them revealed their anti-Nazi feelings and proclaimed their desire to aid the Allies. These prisoners were separated from other German uniform–wearing comrades because they declared themselves loyal to their respective national governments in exile.

Within the larger North Carolina POW camp system, there were real German soldiers who were anti-Nazi, too. For example, the Nazis had condemned Friedrich Wilhelm Hahn, a former member of the Waffen-SS, to two years of imprisonment in the concentration camp at Dachau for “showing favoritism to Jews and political prisoners.” Later “rehabilitated,” Hahn returned to a regular German military unit and was captured by American forces. He became a prisoner at Camp Mackall. Nikolaus Ziegelbauer, a POW in the camp at Ahoskie, was another victim of Nazi “justice.” A German political opponent of the Nazis, he had spent time in concentration camps before being “allowed” to join the German army.

POWs in North Carolina worked on military bases, on local farms, and in agricultural industries—especially pulpwood harvesting—when civilian labor was not available. They largely went unnoticed. Of course, farmers who contracted with the American military for laborers knew of the German presence, but otherwise the federal government kept the POWs a relative secret. One may look in vain for the rare wartime newspaper story about German POWs in the state. Occasionally there was an FBI notice of an escape or a story about the recapture of escaped POWs, but not if the military could capture the escapee without public knowledge. Newspaper coverage and public knowledge were intentionally limited until the end of the war, to uphold the Geneva Convention. Many countries, including the United States and Germany, had signed that international treaty in 1929. It was designed to ensure safe and fair treatment for captured troops. One of its provisions was that prisoners of war not be subjected to public ridicule. Another provision was that POWs should be housed, fed, and clothed in the same manner as the troops of the nation that held them captive. Though there were a total of twenty-nine escape attempts from North Carolina POW camps, only one was “successful.” In 1959 Kurt Rossmeisl—a Camp Butner escapee from the war years—turned himself in to the FBI in Cincinnati.

The attentive general public only learned of the German POW presence in the United States during the final months of World War II, with the liberation of concentration camps and POW camps in Germany. The harsh treatment of concentration camp inmates and some POWs in German hands—compared to what seemed, to some people, to be “coddling” of German POWs in America—aroused a major public outcry in the spring of 1945. Though Germany abided by Geneva Convention rules for the most part when it came to POWs, it took the U.S. Army several months to convince a congressional committee, the press, and the public that the treatment of POWs in the United States followed that same treaty and had saved the lives of American servicemen in German hands.

The attentive general public only learned of the German POW presence in the United States during the final months of World War II, with the liberation of concentration camps and POW camps in Germany. The harsh treatment of concentration camp inmates and some POWs in German hands—compared to what seemed, to some people, to be “coddling” of German POWs in America—aroused a major public outcry in the spring of 1945. Though Germany abided by Geneva Convention rules for the most part when it came to POWs, it took the U.S. Army several months to convince a congressional committee, the press, and the public that the treatment of POWs in the United States followed that same treaty and had saved the lives of American servicemen in German hands.

By the spring of 1946, the final POWs had left North Carolina and American shores. More than half of them spent another year or two as prisoners in England or France, helping to restore those war-torn countries. But many former POWs returned to their native countries with good feelings toward America. Over the last several decades, the author of this article has talked with many former German POWs who spent time in North Carolina and other states, meeting only a handful with negative feelings about their time in America. They generally were treated well and met with inherent friendliness from their guards and civilian agricultural employers. Since the end of the war, many POWs, including Max Reiter, have visited North Carolina and been well received.

Why not? In a newspaper article in November 1945, the state director of the War Manpower Commission said that the POWs had performed nearly two million man-days of labor in North Carolina’s agricultural and other rural industries. Many “Nazi” and “Fascist” POWs turned out to be useful home front workers. Some even became lifelong Tar Heel friends.

*At the time of the publication of this article, Dr. Robert D. Billinger Jr. was the Ruth Davis Horton Professor of History at Wingate University. In 2008 the University Press of Florida published his book Nazi POWs in the Tar Heel State.

Additional Resources:

ANCHOR: Prisoners of War in North Carolina

The Incident Movie: http://www.theincidentmovie.com/

Smithsonian Mag,German POWs in the American Homefront. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history-archaeology/German-POWs-on-the-Ame....

Image Credits

"Crew members of the German U-352, captured in May 1942 off the North Carolina coast after the U.S. Coast Guard sand their vessel, became prisoners of war held at For t Bragg." Image courtesy of the State Archives, North Carolina Office of Archives and History.

Kamler, E. "Watercolor landscape of the barracks at Camp Butner," 1945. Image courtesy of the North Carolina Museum of History.

1 January 2008 | Billinger, Robert D., Jr.