Collet (Collett), John Abraham

fl. 1756–89

John Abraham Collet (Collett), a Swiss military engineer, map maker, captain in the British army, and governor of Fort Johnston, N.C., was probably from Geneva, where his widowed mother, a Moravian, was living in 1768. In the French service during the Seven Years' War (1756–63), Collet served in six campaigns; for the next four years he studied mathematics, drawing, and fortification. He was recommended to Earl Shelburne, secretary of state for the Southern Department, and Viscount William Barrington, secretary at war, by Mr. and Mrs. Henry Grenville as of an "extreme good character and of a very honest, prudent disposition." In May 1767, George III appointed him an army captain and governor of Fort Johnston, at the mouth of the Cape Fear River.

On 4 Nov. Collet presented his credentials to Governor William Tryon at Brunswick. Collet was, with justification, dismayed by what he found. The fort was in "ruinous condition"; no salary was attached to his army commission; and the North Carolina assembly was in no mood, then or later, to vote pay to a British officer or to expend funds on the fort. The only emolument was a nominal health tax on shipping entering the Cape Fear River, a pittance amounting to less than thirty pounds a year. Captain John Dalrymple, the former army commandant, had died suddenly the year before, and Tryon had appointed a wealthy nearby planter, Robert Howe, to succeed him. At Tryon's suggestion, in order to mollify Howe's resentment at his replacement, Collet appointed him second in command and allowed him to retain the shipping tax and quarters in the fort. Before the end of the year, Collet drew a plan of the fort and made a detailed report on the repairs needed to make the fortification defensible. By the end of December, Tryon sent him to New York with the old great seal of the province, which by the royal warrant had to be returned upon receipt of the new seal. Tryon also wrote letters to Thomas Gage and Shelburne, recommending that Collet be made engineer of the Southern Department, with orders to make needed surveys of the coastal areas of the Carolinas. Collet returned from New York disappointed; Gage had neither authority nor funds to establish such a post. In February 1768, Collet wrote a long letter to Shelburne outlining the situation and his financial distress. In September 1768, Tryon appointed him an aide-de-camp on his expedition against the Regulators at Hillsborough, and Collet filled the position with such gallantry and merit that Tryon recommended him for higher service and, upon Collet's return to London early in December, entrusted him with a report on the conditions in the province.

On 4 Nov. Collet presented his credentials to Governor William Tryon at Brunswick. Collet was, with justification, dismayed by what he found. The fort was in "ruinous condition"; no salary was attached to his army commission; and the North Carolina assembly was in no mood, then or later, to vote pay to a British officer or to expend funds on the fort. The only emolument was a nominal health tax on shipping entering the Cape Fear River, a pittance amounting to less than thirty pounds a year. Captain John Dalrymple, the former army commandant, had died suddenly the year before, and Tryon had appointed a wealthy nearby planter, Robert Howe, to succeed him. At Tryon's suggestion, in order to mollify Howe's resentment at his replacement, Collet appointed him second in command and allowed him to retain the shipping tax and quarters in the fort. Before the end of the year, Collet drew a plan of the fort and made a detailed report on the repairs needed to make the fortification defensible. By the end of December, Tryon sent him to New York with the old great seal of the province, which by the royal warrant had to be returned upon receipt of the new seal. Tryon also wrote letters to Thomas Gage and Shelburne, recommending that Collet be made engineer of the Southern Department, with orders to make needed surveys of the coastal areas of the Carolinas. Collet returned from New York disappointed; Gage had neither authority nor funds to establish such a post. In February 1768, Collet wrote a long letter to Shelburne outlining the situation and his financial distress. In September 1768, Tryon appointed him an aide-de-camp on his expedition against the Regulators at Hillsborough, and Collet filled the position with such gallantry and merit that Tryon recommended him for higher service and, upon Collet's return to London early in December, entrusted him with a report on the conditions in the province.

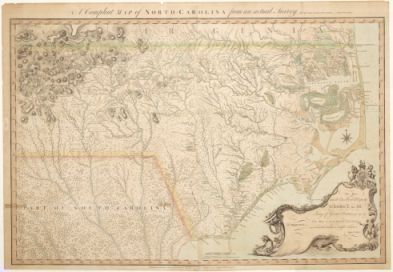

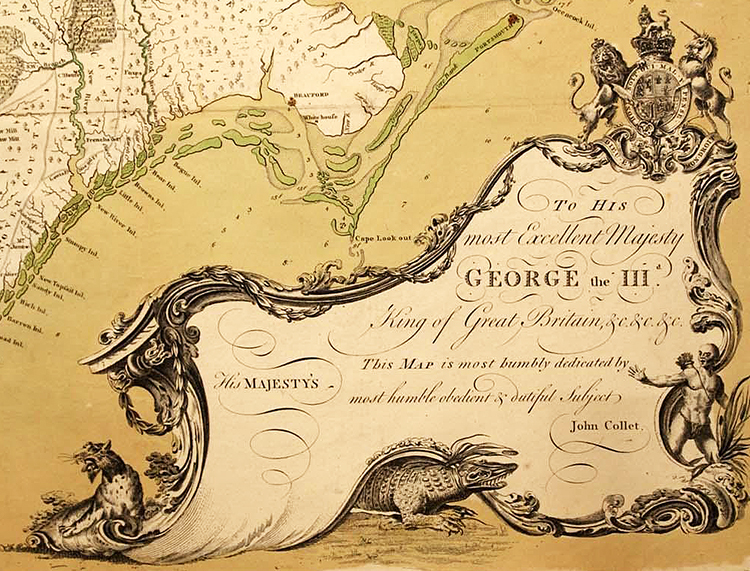

With him, Collet took a manuscript map of North Carolina that extended to the recently established Indian boundary line and delineated the rivers, roads, and settlements in the western frontiers of the province. British authorities had for years urged the colonial governors to send them maps of their provinces, and North Carolina had not previously responded, although problems raised by frontier settlements were pressing. Collet's draft was basically a copy of an unfinished map willed to Tryon by William Churton, surveyor of the Granville District. Churton had died before its completion while surveying the Outer Banks in December 1768. Years before, Churton had contributed the information for the Granville District to Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson's 1751 [1753] map of Virginia, adding information for its 1755 revision; he had continued to improve his map and enlarge the area it covered until the time of his death. Upon reaching London, Collet presented his manuscript to the king, who sponsored the engraved version that Collet published in 1770 at an actual loss, he wrote later, of five hundred pounds. "A Compleat Map of North-Carolina," 28 5/8 × 431/2 inches on a scale of 13 3/4 miles to an inch, was beautifully engraved by I. Bayly and published by S. Hooper. One of the finest provincial maps of the colonial period, it became the basis for the northern half of Henry Mouzon's "North and South Carolina" (1775) and of all other maps of North Carolina until the Price-Strother map of 1808. Although Collet's map of 1770 shows that he had made some surveys, added new details of the western frontiers, and assiduously collected information for the coastal area from Wimble's 1738 map and other sources, the map is essentially Churton's, compiled from twenty years of surveying.

In 1769, while in London, Collet wrote a description of Anson County, reporting on its roads, commerce, and potential agricultural opportunities; later, probably after his return to the province, he sold twenty-five thousand acres that had been granted to him in the center of that county. There is later evidence that he had ambitious plans for land development in North Carolina and South Carolina. In London, although George III employed him personally as a draftsman, Collet waited in vain to receive an appointment commensurate with his training and ability. In the summer of 1772, with disturbing reports from America, the secretary of war, Lord Barrington, ordered him back to resume his post at Fort Johnston.

In 1769, while in London, Collet wrote a description of Anson County, reporting on its roads, commerce, and potential agricultural opportunities; later, probably after his return to the province, he sold twenty-five thousand acres that had been granted to him in the center of that county. There is later evidence that he had ambitious plans for land development in North Carolina and South Carolina. In London, although George III employed him personally as a draftsman, Collet waited in vain to receive an appointment commensurate with his training and ability. In the summer of 1772, with disturbing reports from America, the secretary of war, Lord Barrington, ordered him back to resume his post at Fort Johnston.

Reaching North Carolina early in 1773, Collet found the fort in worsened condition. With the approval of Tryon's successor, Governor Josiah Martin, he undertook to improve and strengthen the fortifications. He showed more zeal than caution and diplomacy, and Dartmouth, Lord Privy Seal, refused government aid for repairs made only "for the security and convenience of commerce of the colony." Unwisely, Collet went ahead; he had expended his own patrimony, and he went heavily into debt. He recruited in New York and transported to the fort fifty men for garrison; he improved the ramparts, built officers' quarters and two barracks for soldiers, bought timber and flagging, and made a hundred thousand bricks. The colonists looked upon these activities with growing suspicion and anger. Although Martin pressured the house of assembly into voting for part of Collet's expenditures, the money was not paid.

By 1775, Collet was "harassed by every means the Americans could devise." They bribed his garrison to desert, finally leaving him with only three or four on whom he could rely of a remaining twelve, and they hindered him from obtaining food and provisions. Infuriated and goaded into rashness, he confiscated the grain on a vessel wrecked nearby, that of Captain Alexander McGregor. Despite Martin's advice, he kept the grain and contemptuously tore up a writ served on him from the office of the attorney general of the province. These incidents formed the chief accusations in an inflammatory "Letter of the People" to Governor Martin, published 10 July 1775. Since March, increasing rumors of a planned attack on the fort came to the ears of the governor and of Collet; by 15 July the patriot Robert Howe, Collet's predecessor at the fort, was on the way with a troop of militia to take the fort. The governor had taken refuge on the armed sloop Cruizer offshore from the fort; he ordered the removal of the fort's cannon, sent by General Gage, as the ammunition had not yet arrived. Collet hastily loaded all the military supplies onto a small transport; on 19 July he saw from the transport a large rebel force enter the fort and destroy all the buildings. They burned his house and stables adjacent to the fort and looted his horses, cattle, carriages, furniture, and other property at a loss, he later claimed, of fifty-nine hundred pounds.

Collet sailed on 21 July to Boston, where he delivered his military cargo to Gage's headquarters. He was immediately assigned to the recruitment and command of "several companies of Volunteers and Light Infantry"; within a month he had enlisted, paid bounty money for, clothed, and drilled 145 men, going into debt a further £1732. But by "an unforseen and cruel circumstance," a new arrival from England, Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Goreham, came with orders to raise a regiment, the Royal American Fencibles, into which Collet and his men were absorbed.

Collet obtained revenge in North Carolina, however, in the southern campaign of 1776 under Sir Henry Clinton: he returned to the Cape Fear on 12 Mar. aboard the armed vessel General Gage and, landing with troops, "that pert little scoundrel" burned the mansion of William Dry in Brunswick; of his unfinished home three miles below Wilmington, William Hooper said, "That hopeful youth made a Bonfire of a country house of mine." On 12 May two regiments under Clinton and Cornwallis landed and destroyed the house of Continental General William Howe, leader of the rebels who had burned the fort and Collet's house.

Sailing north to Nova Scotia under Goreham, Collet returned to New York with Sir William Howe and took part in the attacks on Long Island, the taking of New York, and skirmishes in the Jerseys and at Knightsbridge that fall. Again in Nova Scotia, he was in command of Fort Edward and then cabinet engineer of the general at Halifax. In 1778 he was appointed chief engineer, but rumors of his extravagance apparently prevented confirmation. He was at Fort Cumberland (1777–80) and Fort Howe (1781) in Nova Scotia and made a short campaign in Canada under General Frederick Haldimand.

After his return to England, records of Collet's activities become increasingly sparse. In 1782 he submitted a lengthy proposal for recruiting a regiment of French and German soldiers and officers, with himself as colonel. In the same year, and again later, he submitted memorials to the Treasury for debts incurred in military expenditures in North Carolina and Boston; because an endorsement, dated 6 Nov. 1789, notes that Collet's demand is denied "for expenditures at the fort before the war and is chargeable to the province," it is doubtful that he ever received much compensation. In 1786 he wrote to Lord Shelburne requesting support for a map of Nova Scotia that he was dedicating to the king with royal permission; such a map has not been identified. Thereafter Collet fades from view.

Captain J. A. Collet's identity and career have been erroneously confused with those of two other John Collet(t)s. In 1776, George III appointed his "Trusty and wel beloved" John Collet as British consul at Genoa; from there the consul made reports during and after the war on French and Spanish naval actions in the Mediterranean. More confusing is the American career of John Collet, for twenty years a Philadelphia trader, who joined Lord Dunmore as lieutenant colonel of the Virginia Rangers, served in Browne's Florida Rangers and Carolina Rangers (1777–82), married a Mary Dupont of South Carolina in 1781, wrote memorials to the Loyalist Commission, and died in 1818, survived by his widow.

Collet had excellent qualities; he was energetic, ambitious, capable, and experienced as an officer and engineer. "Amiable and deserving," Governor Martin thought him, echoing the opinions of all earlier officials from Shelburne to Tryon. But he proved extravagant and arrogant at a time when restraint and conciliation were needed. His actions gave an opportunity for inflammatory and exaggerated accusations by patriot agitators; later, Governor Martin also vigorously condemned his conduct as not based on "principles of justice, equity, and charity." Collet's very success in repairing Fort Johnston and his own unwise actions under stress in the spring of 1775 were the catalysts that precipitated the first rebellious military action in the province. His chief and most permanent achievement was his map of North Carolina.

References:

E. W. Andrews and C. M. Andrews, eds., Journal of a Lady of Quality (1921).

William L. Clements Library (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor), for Clinton Papers, Foreign Courts, Gage Papers (American and English Series), Manchester Papers, and Shelburne Papers.

William P. Cumming, North Carolina in Maps (1966), and The Southeast in Early Maps (1958, 1962).

Adelaide L. Fries, ed., Records of the Moravians in North Carolina, vol. 1 (1922).

Historical Manuscripts Commission, American MSS in the Royal Institution, 4 vols. (1904–9).

Lansdowne MSS 1219, ff. 83–86 (British Museum).

Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., for sundry papers.

North Carolina State Archives (Raleigh), for P.R.O. Sainsbury Transcripts.

P.R.O. (London), A.O. 12/76, 101, 102.

ibid., A.O. 13/118, ff. 204–8 (Collet Memorial).

ibid., A.O. 118/118.

ibid., A.O. Bundle 87.

ibid., C.O. 324/15.

ibid., Misc. Corr. 154/23–6.

Hugh F. Rankin, The North Carolina Continentals (1971).

William L. Saunders, ed., Colonial Records of North Carolina, 10 vols. (1886–90).

Treasury (London), 1/646, ff. 212–13 (Collet Memorial).

ibid., 52/65.

ibid., 79/121.

Additional Resources:

"Collet. A Compleat Map of North Carolina (1770)." Craven County Digital History Exhibit. New Bern-Craven County Public Library. 2009. http://newbern.cpclib.org/digital/TP1956014001.html (accessed July 22, 2013).

"Re-Stating the 1770 Churton-Collet map of North Carolina." North Carolina Map Blog (blog). The William P. Cumming Map Society. May 12, 2013. http://blog.ncmaps.org/index.php/re-stating-the-1770-churton-collet-map-of-north-carolina/ (accessed July 22, 2013).

Steelman, Ben. "Brunswick map tells tales of coast's Colonial past." Wilmington Morning Star. December 12, 1983. 1C. Google News. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=2yFOAAAAIBAJ&sjid=hRMEAAAAIBAJ&pg=3964%2C3219964 (accessed July 22, 2013).

North Carolina General Assembly "Account of the reimbursement to John Collet for expenditures at Fort Johnston. March 1774." Colonial and State Records of North Carolina. Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.html/document/csr09-0257 (accessed July 22, 2013).

Image Credits:

Collett, John. "A Compleat map of North-Carolina from an actual survey," 1770. North Carolina Maps, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries. http://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/ncmaps/id/467 (accessed September 27, 2012).

Collet, John, J Bayly, and S Hooper. A compleat map of North-Carolina from an actual survey. London: S. Hooper, 1770. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/83693769/ (accessed July 13, 2023).

1 January 1979 | Cumming, William P.