Mississippi Navigation Crisis

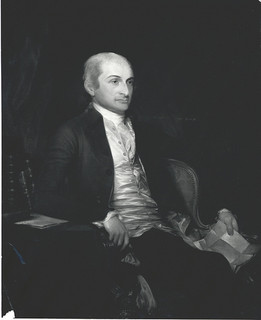

The Mississippi Navigation Crisis of 1786-88 was the first serious North-South political quarrel in U.S. history. Some of the most outspoken and vociferous opponents to Secretary of State John Jay's proposed treaty with Spain-the conditions of which threatened to trade away the southern states' interest in western lands and the navigation of the Mississippi River for northern fishing, shipping, and commercial privileges-were political leaders from North Carolina. They included Timothy Bloodworth, Richard Caswell, Hugh Williamson, Benjamin Hawkins, and William Blount.

The Mississippi Navigation Crisis of 1786-88 was the first serious North-South political quarrel in U.S. history. Some of the most outspoken and vociferous opponents to Secretary of State John Jay's proposed treaty with Spain-the conditions of which threatened to trade away the southern states' interest in western lands and the navigation of the Mississippi River for northern fishing, shipping, and commercial privileges-were political leaders from North Carolina. They included Timothy Bloodworth, Richard Caswell, Hugh Williamson, Benjamin Hawkins, and William Blount.

From the end of May 1786 until September 1788, Jay of New York, Rufus King of Massachusetts, and other northern congressmen argued that the critical situation of American trade and foreign relations warranted forbearing navigation of the Mississippi River for 25 years. In exchange for exclusive control of the river, Spain promised to open ports on the Spanish mainland and its Mediterranean islands, as well as in the Canary Islands and the Azores, to U.S. ships and their merchandise. The northern states, which controlled American shipping and freighting, stood to benefit most from the proposed treaty. In addition, many northern political leaders believed that a closed Mississippi River would slow western expansion and thereby maintain eastern land values, free labor supplies, and the political dominance of the seven northern states. Delegates from Virginia and North Carolina stood their ground in Congress, even when numerous northern representatives met secretly to discuss forming a separate confederacy.

The Mississippi Navigation Crisis was one of the most significant precipitating events of the constitutional convention. During the convention, the subject was fully discussed and was one of the southerners' strongest justifications for requiring in Article II, section 2, clause 2, of the Constitution that no treaty be signed with a foreign nation without the consent of two-thirds of the Senate. By requiring a two-thirds majority, they ensured that a southern bloc could obstruct the passage of any treaty injurious to the South. The Navigation Crisis was also an important bargaining point in the three-fifths slavery compromise.

Delegates from North Carolina urged the motion in the Continental Congress that finally put an end to the proposed treaty with Spain. On 16 Sept. 1788 Congress passed the North Carolina motion that declared Mississippi navigation an "essential right of the United States." The issue was deferred to the "new Government." Americans did not formally gain navigation rights to the Mississippi until the signing of Pinckney's Treaty in 1795; they did not enjoy a completely free and uninterrupted commerce on the river until the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

References:

Michael Allen, "The Mississippi River Debate, 1785-87," Tennessee Historical Quarterly 36 (Winter 1977).

Samuel Flagg Bemis, Pinckney's Treaty (1960).

Eli F. Merritt, "Secret Conflict and Sectional Compromise: The Mississippi River Question and the United States Constitution," American Journal of Legal History 35 (April 1991).

Arthur Preston Whitaker, The Mississippi Question, 1795-1803 (1934).

Additional Resources:

"Navigation of the Mississippi River." History Department. University of Wisconsin-Madison. Center for the Study of the American Constitution. http://csac.history.wisc.edu/navigation_of_mississippi.htm (accessed October 30, 2012).

Coulter, E. Merton. "The Efforts of the Democratic Societies of the West to open the Navigation of the Mississippi." Mississippi Valley Historical Review 11. No. 3 Dec. 1924. pp.376‑389. http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Journals/MVHR/11/3/Opening_the_Navigation_of_the_Mississippi*.html (accessed October 30, 2012).

Image Credits:

"John Jay, U.S. Secretary of Foreign Affairs." Posted February 15, 2008. Flickr user U.S. Department of State. https://www.flickr.com/photos/statephotos/2266427407/in/photostream (accessed October 30, 2012).

1 January 2006 | Merritt, Eli F.