A History of Medical Teaching in North Carolina

by Francine Mary Netter Roberson.

Copyright of the author, 2010.

See also: Hospitals; Medical Society; Leonard Medical School

Summary

From apprenticeship to a rigorous standardized course of study, medical instruction in North Carolina has progressed step by step over the last 200 years. The education of physicians and surgeons conforms to standards set down by Abraham Flexner’s report, to craft physicians differentiated by their service to the public good.

Seven medical schools have been founded in North Carolina since the end of the Civil War. Three have closed. The four remaining -- the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Duke University School of Medicine and the Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University -- have grown to become outstanding medical schools, providing superb patient care in the community, excellence in medical education and leading biomedical research, serving the people of North Carolina and beyond.

Introduction

Medical education in North Carolina and throughout the United States is today uniform and exacting. In contrast, the training of medical doctors in the early history of North Carolina was irregular and often of poor quality. The founding of the American Medical Association and the North Carolina Medical Society in the middle of the 19th century heralded the way for the establishment of the four modern medical schools now serving the state.

The Early Years – the 18th Century

Before there were medical schools in North Carolina, those young men – women being generally excluded – who wished to become physicians could seek a medical education in one of three ways. The most common path was a three- to seven-year apprenticeship to a doctor in the community. The quality of such instruction varied greatly, with some physicians taking great care to provide instruction and others giving little or none at all. If the doctor had a library, the young apprentice might have access to medical books and journals.

Before there were medical schools in North Carolina, those young men – women being generally excluded – who wished to become physicians could seek a medical education in one of three ways. The most common path was a three- to seven-year apprenticeship to a doctor in the community. The quality of such instruction varied greatly, with some physicians taking great care to provide instruction and others giving little or none at all. If the doctor had a library, the young apprentice might have access to medical books and journals.

Some industrious medical practioners operated private schools for profit, where they instructed groups of students, usually by lecture. Charles Harris (1767-1825) was a doctor, trained at the University of Pennsylvania, who practiced 40 years in Cabarrus County. He ran an apprenticeship school and during its operation trained about 90 students.

Those seeking a medical education in a university system journeyed to one of the medical colleges in other states, which offered both lecture and clinical training. In the United Sates before 1800, there were but five medical schools – University of Pennsylvania (1765); Kings College (1768, which became Columbia University; Harvard College (1782); Dartmouth (1798) and Transylvania University (1799) in Lexington Kentucky. A more well-to-do student might venture to study at one of the prestigious schools in Europe, principally in England, Scotland, France or Germany.

For both the apprentice and medical school student, training varied greatly in substance and philosophy. No standardization existed for the medical degree and schools set their own requirements. Furthermore, the State of North Carolina and most other states did not license the practice of medicine. Consequently, the competence of physicians varied widely.

The American Medical Association and the North Carolina Medical Society

In 1846, Dr. Nathan S. Davis of New York led the founding of the American Medical Association (AMA). Two hundred fifty delegates from 28 states attended the first meeting, held at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, where they adopted both a code of ethics and the first national standards for medical education, including laboratory study and patient care in a hospital.

In 1849 a group of 25 physicians organized the North Carolina Medical Society, electing Dr. Edmund Strudwick President. He had received his medical education as an apprentice to Dr. James Webb in Hillsborough and then at the University of Pennsylvania where he received his medical degree. In his 1850 address to the Society, he appealed for accurate record keeping by physicians. He recommended that the North Carolina Legislature pass a law compelling registration of marriages, births and deaths. He also pushed for the right to dissection of criminal and charity cases for educational purposes.

The First Chartered Schools

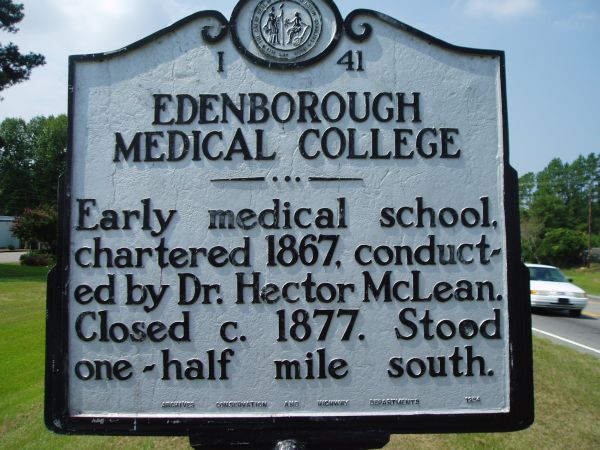

Dr. Hector McLean founded the Edenborough Medical College in Robeson County in 1867. It was the first medical school chartered by the North Carolina General Assembly. Students studied dissection, pharmacy and clinical medicine. When Dr. McLean died in 1877, the school closed.

Dr. Hector McLean founded the Edenborough Medical College in Robeson County in 1867. It was the first medical school chartered by the North Carolina General Assembly. Students studied dissection, pharmacy and clinical medicine. When Dr. McLean died in 1877, the school closed.

In 1879, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill sponsored the School of Medicine, a two-year curriculum with Dr. Thomas W. Harris as Dean and professor of anatomy, Professor A. Fletcher Redd, chemistry, and Professor Frederic W. Simonds, botany and physiology. But, receiving no salary from the University, Dr. Harris continued to practice medicine and, when he resigned from the University in 1885 to devote himself fulltime to his practice, the school closed.

In 1882, at Shaw University in Raleigh, Henry Martin Tupper founded the Leonard Medical School for the education of black Americans. Tupper’s brother-in-law, Judson Wade Leonard, donated $5000 and the North Carolina Legislature donated an acre of land for the school site. The Leonard family donated additional funds for a hospital, erected adjacent to the medical dormitory, and the Leonard Medical School became the first four-year medical college in the North Carolina.

The University of North Carolina reopened the medical school in 1890 with Dr. Richard H. Whitehead as dean and anatomy professor. The course offering was a one-year course of study, which in 1896 expanded to two years. Dr. Hubert A. Royster succeeded Dr. Whitehead as dean in 1902, at which time Drs. Whitehead and Royster formed the University Medical Department at Raleigh, to provide two years of clinical instruction at the hospitals in Raleigh -- Rex, St. Agnes, and Dorothea Dix Hospitals and the Raleigh Dispensary. Many of the same physicians who taught at the Leonard Medical School taught also at the Raleigh Medical Department. The University of North Carolina now offered a four-year curriculum in medical training.

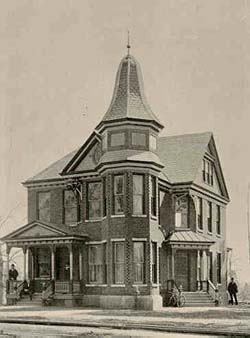

North Carolina Medical College began in 1887 at Davidson College as Davidson School of Medicine. The offering was originally a one-year preparatory course of study for students seeking admission to other medical schools. In 1893 the medical school incorporated and the course of study expanded to a three-year curriculum to train physicians. In 1902, the school added a year of clinical work at Presbyterian and Good Samaritan hospitals in Charlotte, thus expanding the program to four years. The entire medical school relocated to Charlotte in 1907 and was renamed the North Carolina Medical School.

North Carolina Medical College began in 1887 at Davidson College as Davidson School of Medicine. The offering was originally a one-year preparatory course of study for students seeking admission to other medical schools. In 1893 the medical school incorporated and the course of study expanded to a three-year curriculum to train physicians. In 1902, the school added a year of clinical work at Presbyterian and Good Samaritan hospitals in Charlotte, thus expanding the program to four years. The entire medical school relocated to Charlotte in 1907 and was renamed the North Carolina Medical School.

Wake Forest College, then located in Wake County, founded its medical school in 1902 as a two-year non-clinical course of study. Thus, at the beginning of the 20th century, North Carolina had four medical schools – University of North Carolina Medical School, Leonard Medical School, North Carolina Medical College (all four year schools offering didactic and clinical training), and Wake Forest College Medical School, a two year school whose students completed their clinical training elsewhere. Schools remained in charge of determining curriculum and the AMA continued to lobby for standardization of medical education.

The Flexner Report

At the turn of the 20th century, medicine was proving to be based on science. Gone were the days of bleeding and purging. The skills for medical practice were best learned through laboratory experimentation and patient care, the ideal curriculum consisting of two years training in laboratory sciences and two years clinical rotation. In an effort to push medical schools toward adopting such demanding standardized medical education, the AMA created the Council on Medical Education (CME). In 1908, the CME asked the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching to make a survey of medical education in America. Abraham Flexner, an educational reformist attracting attention for his scrutiny of teaching methods in American colleges, led the effort.

Flexner visited every medical school in the United States. He found a large disparity among them. Few had the financial wherewithal to implement the demanding standards of a well-equipped laboratory, a nearby teaching hospital and qualified faculty. He argued for the closure of proprietary medical schools, which by nature of their business model were inconsistent with medical education as a public health issue, in favor of schools with sufficient resources. With the founding of the Federation of State Licensing Boards in 1912, and its adoption of the AMA’s academic standards, the CME’s recommendations became law.

Leonard Medical School, North Carolina Medical College and University of North Carolina received unsatisfactory ratings in Flexner’s report. Leonard Medical School suspended clinical training in 1914 and in 1918, the school closed. North Carolina Medical College merged with the Medical College of Virginia in 1914 and conferred degrees until 1917.

The University of North Carolina closed the Medical Department at Raleigh and concentrated its resources on upgrading and improving the two-year curriculum in Chapel Hill. Students transferred to four-year schools to complete their clinical work.

North Carolina Medical Schools in the 20th Century

In 1922, the Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina asked the legislature to build a hospital in Chapel Hill. It was to be named Memorial Hospital, for those North Carolinians fallen in the Great War. Such a facility would allow the medical school to include clinical training in an expanded four-year program. But in 1923 the legislature turned down the request, ostensibly for financial reasons.

Because of its close physical proximity to Chapel Hill, Duke University in Durham suggested to the University of North Carolina that they form a collaborative effort – medical students would take the first two years of study at the existing facilities in Chapel Hill and the last two years at Trinity and Watts Hospital in Durham, and both schools would confer the MD degree. The North Carolina Legislature and the Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina declined the offer on the basis that since Duke University had its foundation in the Methodist tradition and as the University of North Carolina was a public university, it was inappropriate to work together.

Through the philanthropy of James B. Duke, Duke University had the funding and built a first class hospital and four-year medical school. The hospital opened to patients in July of 1930 and in October of that year admitted first and third year students – women as well as men. The close proximity of the Duke hospital to Chapel Hill was reason for the North Carolina Legislature to continue to deny permission for funding for a hospital in Chapel Hill, and the University of North Carolina continued as a two-year school.

Then in 1941, the Bowman Gray Foundation, founded by the estate of Bowman Gray, Sr., the philanthropic president of R. J. Reynolds, offered funds to the medical school at the University of North Carolina for it to expand to a four-year school, but on the condition that the medical school move to Winston Salem. The Board of Trustees, thinking that the school must remain on the Chapel Hill campus, declined. Wake Forest University jumped at the offer. The four-year school, built adjacent to Baptist Hospital and renamed to the Bowman Gray School of Medicine, opened in 1941, renamed in 1997 as the Wake Forest University School of Medicine.

In 1948, the North Carolina Legislature approved funds for building Memorial Hospital in Chapel Hill. The hospital opened in 1952 and the University of North Carolina Medical School expanded the curriculum to include clinical training, and in 1954 the University of North Carolina began awarding the MD degree.

The standards resulting from the Flexner report made medical education an expensive process. Small and rural medical schools closed, leaving a paucity of family care physicians, particularly in rural areas. The standards for admission for medical school also become more stringent as a result of the report, making admission more difficult and providing less opportunity for the disadvantaged to become doctors.

The medical school at East Carolina University in Greenville addresses just those problems. It began as a one-year school, whose students continued their medical education in Chapel Hill, and in 1974, with funds appropriated by the North Carolina Legislature, expanded to a four-year school. Its mission is to train primary care physicians to serve the rural areas of North Carolina; to provide health care to the citizens of eastern North Carolina; and to make medical education available to deserving minority and underprivileged students. In 1999 it was renamed the Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University.

References and additional resources:

American Medical Association. "Our History." https://www.ama-assn.org/about, (accessed 6/29/2010).

Beck, Andrew H., "The Flexner Report and the Standardization of American Medical Education." JAMA. 291, no. 17 (2004): 2139-2140, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/198677, (accessed 6/25/2010).

Berryhill, W. R., “The Location of a Medical School: Considerations on Favor of Locating a Medical School on a University Campus,” Proceedings of the Annual Congress on Medical Education and Licensure, Chicago, Feb 6-7, 1950.

Blackburn Jr., Charles, "Making History: Leonard Medical School." Our State Magazine. Sept. 2006. Republished at https://www.shawu.edu/assets/Making_History.pdf (accessed 6/25/2010).

Blake, John B. "The Development of Anatomical Acts." Journal of Medical Education. 30, no. 8, (1955): 431-39.

Brody School of Medicine. "History: A Legacy of Commitment," https://www.ecu.edu/cs-dhs/med/history.cfm, (accessed 6/25/2010).

Campbell, Walter C. 2006. Foundation for Excellence: 75 Years of Duke Medicine, Duke University Medical Center Library.

Davis, Chester. "Gray School A Medical 'Miracle.'" Winston-Salem Journal-Sentinel. Sept. 10, 1961. Reprinted at https://history.wfu.edu/ (accessed 7/2/2010).

Duke University. "A Brief Narrative History." https://library.duke.edu/rubenstein/uarchives/history/articles/narrative-history, (accessed 7/2/2010).

Duke Medical Center Historical Publications, https://library.duke.edu/rubenstein/history-of-medicine, (accessed 6/25/2010).

Durham Chamber of Commerce. "Neighborhoods." https://durhamchamber.org/ (accessed 7/2/2010).

Endangered Durham blog. http://endangereddurham.blogspot.com/2007/01/wattsmcpherson-hospitals-chancellory.html. (accessed 7/2/2010).

Federation of State Medical Boards, "FSMB History," https://www.fsmb.org/about-fsmb/ , (accessed 7/2/2010).

Garrison, Donna S., “The Wake Forest Era and the Two-year School: 1902-1941,” Southern Medical Journal. 95, no 10, (2002): 1111.

"History of UNC Medicine." https://www.med.unc.edu/about/, (accessed 6/25/2010).

Jenkins. George B., "The Legal Status of Dissecting." Anatomical Record, 7, no. 11, (1913): 387-99.

Long, Dorothy, ed. Medicine in North Carolina; essays in the history of medical science and medical service, 1524-1960, North Carolina Medical Society, Raleigh, NC, 2 vols. 1972.

McLendon, William W., Floyd W. Denny, and William B. Blythe. 2007. Bettering the health of the people: W. Reece Berryhill, the UNC School of Medicine, and the North Carolina Good Health movement. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library.

"North Carolina Medical College." AMA’s American Medical Directory of 1916, p. 80

North Carolina Medical Society. 150 Years of Leadership: The History of the North Carolina Medical Society’s Pioneering Physician Leaders. https://ncmedsoc.org/, (accessed 6/25/2010).

North Carolina Medical Society. "About NCMS." https://ncmedsoc.org/, (accessed 6/25/2010).

Routh, Donald K., Clarke, Mary G., “Psychology in a Medical School,” Professional Psychology. 7, no.1, (1976): 94-106.

Thomas, Karen Kruse, "Dr. Jim Crow: The University of North Carolina, the Regional Medical School for Negroes, and the Desegregation of Southern Medical Education, 1945-1960", Journal of African American History. 88, no 3, (2003): 223-244.

Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center, The Fact Book, p. 7, https://www.wakehealth.edu/about-us, (accessed 6/25/2010).

Wake Forest University School of Medicine, 2009-2010 The Bulletin: New Series. July 2009, 104, no. 7.

Image Credits:

"Mortar and pestle." NC Museum of History. 1775. Accession no. H.1947.43.5. Online collections. Accessed Mar. 13, 2024. https://collections.ncdcr.gov/mDetail.aspx?rID=1947.43.5&db=objects&dir=MOH MUSEUMOFHISTORY.

North Carolina Office of Archives & History. "Edenborough Medical College I-41." North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program. Accessed Mar. 13, 2024. https://ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=I-41.

"North Carolina Medical School Building at Davidson College." Davidson College Archives & Special Collections. Accessed Mar. 13, 2024. https://davidsonarchivesandspecialcollections.org/archives/encyclopedia/north-carolina-medical-college.

7 July 2010 | Roberson, Francine Mary Netter