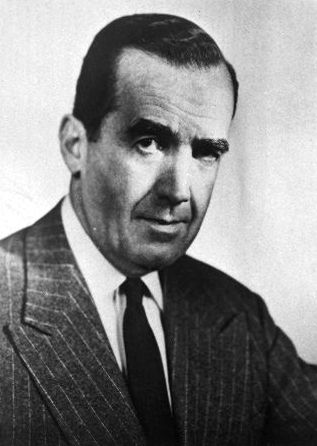

Murrow, Edward Roscoe

25 Apr. 1908–27 Apr. 1965

See also: Edward R. Murrow

Edward Roscoe Murrow, news broadcaster and government official, originally named Egbert, was born near Centre Quaker Meetinghouse in Guilford County on Polecat Creek, the youngest of three sons of Egbert Roscoe and Ethel Lamb Murrow, strict Quakers. Even so, the elder Murrow enlisted in the army during the Spanish-American War and was sent to Vancouver Barracks across the Columbia River in the Washington Territory near Portland, Oreg. Following this service he returned to Guilford County and married. After a few years, when their son, Egbert [Edward], was "a little fellow," the Murrows moved to the state of Washington, where some relatives had taken up residence many years before. They lived there for a year or so, then returned to Guilford County. In 1913 they moved back to Washington, settling at Blanchard in the northwestern corner of the state.

Numerous explanations have been given for the final move, some of them remembered for many years but never published. Low farm prices, asthma attacks suffered by Ethel Murrow, and the lure of the Pacific Northwest, however, were strong reasons. In 1925 the family moved to Beaver Camp, a logging camp in the Olympic rain forest four miles from the Pacific Ocean. Here, when he was seventeen, Murrow worked as an axman with a logging crew. Somewhere along the way, the young man dropped the name Egbert and became Edward or Ed to the crew and his friends. It was not until 1944, however, that he legally changed his name.

Having saved some money and with the help of his brothers, Murrow entered Washington State College at Pullman in the fall of 1926. Intending to major in business administration, he discovered a kindly and capable teacher of speech, Ida Lou Anderson. She was from Tennessee, and in her Murrow found a kindred spirit. Active in sports, debating, drama, and campus politics, he held several student jobs, became class president, and was top ROTC cadet. Among his honors and accomplishments was election to Phi Beta Kappa. Through his activities with the National Student Federation of America, Murrow attended a convention in Palo Alto, Calif., where he took the floor to criticize students for being unduly concerned with "fraternities, football and fun" as the Great Depression began to take effect. He made such a good impression that he was elected national president of the NSFA for 1930–31.

Following graduation in June 1930, Murrow was commissioned a second lieutenant in the inactive reserve. He left immediately for New York, where the offices of the NSFA were located, and soon afterwards went to Europe to attend an international students' meeting in Brussels. There he associated with young people from across Europe and learned firsthand of the problems created by the aftermath of World War I. Back home again, he spoke at meetings across the nation and assisted in an exchange program with foreign students.

Following graduation in June 1930, Murrow was commissioned a second lieutenant in the inactive reserve. He left immediately for New York, where the offices of the NSFA were located, and soon afterwards went to Europe to attend an international students' meeting in Brussels. There he associated with young people from across Europe and learned firsthand of the problems created by the aftermath of World War I. Back home again, he spoke at meetings across the nation and assisted in an exchange program with foreign students.

In New York, Murrow persuaded the Columbia Broadcasting System, then only a little over two years old, to broadcast a program, "The University of the Air," for the NSFA. For the program he succeeded in recruiting, live, such people as Einstein and Tagore and, by the then-novel transatlantic wireless, such notables as Ramsay MacDonald from Great Britain and President von Hindenburg from Germany.

While president of NSFA, Murrow boarded the train in North Carolina to go to a convention in New Orleans. On the way down he met Janet Huntington Brewster, from Middletown, Conn., who was traveling to the same meeting as a delegate from Mount Holyoke College. They were married in the fall of 1934, and their first and only child, Charles Casey, was born in London on 6 Nov. 1945.

In 1935 Murrow became "director of talks" and education for CBS, still a small network with only a hundred stations. Two years later he was sent to Europe to broadcast special events—the coronation of King George VI and festivals and ceremonies of various kinds. In March 1938, while in Vienna, he transmitted his observations of Hitler's annexation of Austria. Direct journalism was born on this occasion and so was Murrow's rise to fame. In turn, he became CBS's European director, war correspondent (1939–45), and vice-president and director of public affairs. Stationed in London during much of World War II, he described in the first person German bombing raids on the city with the sound of sirens and explosions in the background. His moving and graphic terms, broadcast from the heart of London, contributed to the growth of American concern about the war and sympathy for Britain. His wife, Janet, also broadcast her observations of life among the mass of people in England. To the British Murrow became a hero, and in time he was made a Knight Commander of the British Empire.

Initially, of course, Murrow's medium was radio, but with the advent of television he became an even more notable figure. Among the programs that he developed were "Person to Person," "See It Now," "Small World," and "CBS Reports." All of these drew large and devoted audiences, as did his lectures on international relations across the United States and in Europe. Edward R. Murrow played a particularly crucial role in alerting the nation to the significance of Senator Joseph McCarthy's groundless "witch-hunt" for Communists in the government.

Resigning from CBS, Murrow became head of the U.S. Information Agency in 1961. He served in the post until 1964, when ill health forced his retirement. An inveterate cigarette smoker, he developed lung cancer which apparently spread to his brain. At his insistence, he was taken from a New York hospital to his rural home in Pawling, N.Y., where he died two days after his fifty-seventh birthday. His ashes were scattered across his farm.

Murrow's contributions to the nation were recognized by the awarding of numerous honorary degrees, including that of LL.D. by The University of North Carolina in 1946. He received the Freedom House Award (1954), an Emmy award (1956), and the President's Medal of Freedom (1964). He was the author of This is London and many articles in educational journals.

References:

Edward Bliss, Jr., "Remembering Edward R. Murrow," Saturday Review, 31 May 1971.

DAB, vol. 7, supp. (1981).

Alexander Kendrick, Prime Time: The Life of Edward R. Murrow (1969).

Charles Kuralt, "Edward R. Murrow," North Carolina Historical Review 48 (April 1971).

Letter from Vera Hamilton (4 Mar. 1980), an unsigned letter (4 Mar. 1980), and letter from Lawrence W. Routh (15 Mar. 1980), all from Greensboro (possession of William S. Powell).

R. Franklin Smith, Edward R. Murrow: The War Years (1978).

Ann M. Sperber, Murrow: His Life and Times (1986).

Who Was Who in America, vol. 4 (1968).

Additional Resources:

"Murrow, Edward R.: U.S. Broadcast Journalist." The Museum of Broadcast Communications, Chicago, Ill. http://www.museum.tv/eotv/murrowedwar.htm

"Edward R. Murrow, Broadcaster And Ex-Chief of U.S.I.A., Dies." The New York Times. April 28, 1965. http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/bday/0425.html

"The Life and Work of Edward R. Murrow, an archives exhibit." Digital Collections and Archives, The Murrow Center, Tufts University. http://dca.lib.tufts.edu/features/murrow/exhibit/index.html

"Edward R. Murrow This Reporter." American Masters. PBS. February 2nd, 2007. http://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/episodes/edward-r-murrow/this-reporter/513/

Image Credits:

Edward R. Murrow - See It Now (March 9, 1954), YouTube video. posted by Justin Hillyard, Aug 22, 2009. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=anNEJJYLU8M (accessed November 22, 2013).

"Portrait of Edward R. Murrow. Date from negative sleeve." Photograph. Daily Reflector Negative Collection, Digital Collections, J.Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University. http://digital.lib.ecu.edu/13843

1 January 1991 | Powell, William S.